Overview

Healthcare providers should be aware of dermatologic conditions associated with or worsened by cigarette smoking. In the context of medical and cosmetic skin health, providers can play a key role in counseling patients on tobacco cessation to minimize smoking-related dermatologic surgical complications and severity of skin disorders.

This article reviews skin conditions associated with or influenced by cigarette smoking. [1]

Wound Healing and Premature Skin Aging

Poor wound healing

Smoking has repeatedly been shown to have deleterious effects on healing skin wounds. Cigarette smoking has been linked with numerous postoperative complications, including wound infections, dehiscence, flap and graft necrosis, and decreased wound tensile strength. [2] In a study from Wahie and Lawrence, smokers showed a much higher rate of wound infection and dehiscence (64% vs 12%) compared with nonsmokers after skin biopsies. [3]

When flaps or grafts are used, smokers have a higher risk of necrosis. Goldminz and Bennett reviewed 916 flaps and full-thickness skin grafts and found that 1 pack-per-day (ppd) smokers had 3 times the frequency of necrosis as nonsmokers. Patients who smoked 2 ppd had necrosis 6 times more frequently than nonsmokers. [4]

Smoking likely causes delayed wound healing and wound-related complications through many mechanisms, such as the following:

-

Vasoconstriction: Peripheral blood flow decreases by 30-40% within minutes after smoke inhalation, compromising tissue oxygenation and wound healing. [5]

-

Prothrombotic effects: Nicotine increases platelet adhesiveness by inhibiting prostacyclin, leading to microvascular occlusion and tissue ischemia. [6]

-

Altered wound inflammation and contraction: Tobacco inhibits endothelial cell and fibroblast function, nitric oxide synthase activity, vascular endothelial growth factor production, and collagen synthesis. [7]

Although no set guidelines have been established, recent literature by Gill et al recommends the following [7] :

-

Counsel patients on smoking cessation and potential complications prior to surgery.

-

Recommend patients discontinue smoking at least 2 weeks before and 1 week after surgery. Nicotine replacement therapy can be used.

-

For heavy smokers who have difficulty with cessation, reduce smoking to less than 1 ppd.

-

The dermatologic surgeon may consider limiting tissue dissection and extensive undermining in the deep subcutaneous plane.

-

For larger flaps, the dermatologic surgeon may consider using a delayed phenomenon method to increase flap viability.

Rhytides (wrinkles) and skin aging

The association between smoking and rhytides has been long established and can be a cause of significant distress among tobacco users. In many smokers, the threat of facial wrinkling is a greater motivator to quit than the threat of lung cancer or other life-threatening smoking-related diseases. [8]

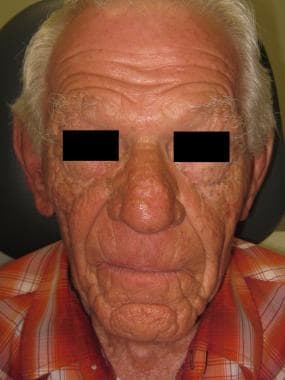

In 1985, the clinical features of a "smoker's face" were described (see the image below), including prominent facial wrinkles, prominence of underlying bony contours, atrophic skin, and plethoric, slightly orange, purple, or red complexion. [9] Women appear to be more susceptible to the wrinkling effects of smoking than men. Ippen and Ippen found that when compared with female nonsmokers, most female smokers had "cigarette skin", which they defined as gray, pale, and wrinkled. [10] Cigarette smoking is an independent risk factor for rhytides; however, sun exposure has a synergistic effect on skin aging. [11]

Facial features consistent with "smoker's face" characterized by prominent facial rhytides, dyschromia, atrophic skin, and prominence of underlying bony contours.

Facial features consistent with "smoker's face" characterized by prominent facial rhytides, dyschromia, atrophic skin, and prominence of underlying bony contours.

Favre-Racouchot syndrome (see image below), a condition characterized by deep wrinkles and comedone formation, was found by Keough et al to be more common in smokers than in nonsmokers. [12]

Favre-Racouchot syndrome is a condition characterized by deep rhytides and comedone formation linked with smoking and solar damage.

Favre-Racouchot syndrome is a condition characterized by deep rhytides and comedone formation linked with smoking and solar damage.

The exact mechanism by which smoking causes wrinkling is poorly understood. Some proposed mechanisms include the following [7, 13, 14] :

-

Ultraviolet-activated phototoxic properties of tobacco smoke

-

Altered connective tissue: Elastin from non–sun-exposed skin in smokers is more fragmented than in nonsmokers.

-

Increased reactive oxygen species, which are implicated in accelerated skin aging

-

Increase in matrix metalloproteinases leading to breakdown of collagen, elastic fibers, and proteoglycans

Skin Conditions

Oral and mucocutaneous disorders

Tobacco has been shown to be an independent risk factor for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Risk is further increased with excess alcohol consumption. All forms of tobacco, including smokeless tobacco, increase the risk of oral cancer. [2, 15, 16]

Smoking is associated with numerous characteristic mucocutaneous changes, such as the following:

-

Nicotine stomatitis (smoker's palate) - Hard palate discoloration, fissuring, and minor salivary gland edema caused by increased heat [17] ; more common in pipe smokers

-

Leukokeratosis nicotina glossi (smoker’s tongue) - Black hairy tongue

-

Smoker’s melanosis - Gingival hyperpigmentation due to increased melanin in basal layer of epidermis [18]

-

Acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis

-

Periodontitis

-

Painful palatal erosions and tooth abrasions [2]

-

Oral leukoplakia

Nail and hair disorders

Smoking has been associated with several hair and nail disorders, such as the following:

-

Smoker’s nails - Yellow and brown discolored fingernails

-

Harlequin nail or quitter’s nail - Demarcation between distal pigmented nail and proximal normal nail upon smoking cessation [19]

-

Androgenetic alopecia [2]

-

Premature gray hair

-

Smoker's mustache - Analogous to smoker's nails; yellow or brown discolored facial hair [20]

Hidradenitis suppurativa

Hidradenitis suppurativa, a chronic inflammatory skin disease in apocrine glands, occurs more frequently in smokers. It is characterized by recurrent boil-like nodules, sinus tract formation, and subsequent scarring primarily in intertriginous areas of skin. [21]

A study by Breitkoph et al evaluated 149 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa and found that 84% of females and 85% of males were smoker’s at disease onset. [22] A recent larger study of 302 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa and 906 controls showed 76% of hidradenitis suppurativa patients were current smokers versus 25% for controls. [23] The mechanism of this association is still unclear, but it has been suggested nicotine alters immune cell function and epidermal hyperplasia, leading to occlusion and rupture of hair follicles. [24]

Psoriasis

Smokers are at increased risk of developing psoriasis and show lower rates of clinical improvement with treatment. Patients who smoke are more likely to have greater disease severity. [25, 26] Palmoplantar pustulosis, a variant of psoriasis, has been shown to have a stronger association with smoking. In one study, 95% of patients were current or former smokers at onset of palmoplantar pustulosis. [27] Female smokers have a 74 times higher risk of developing palmoplantar pustulosis compared with nonsmoking women of the same age. [28]

Lupus

Development of systemic lupus erythematosus, as well as increased disease severity, has been associated with smoking. [29, 30] Cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE), including discoid lupus erythematosus and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, are more prevalent among smokers. [31, 32, 33, 1] The association of smoking and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus appears to be much more prominent in men. Perhaps more important, smoking has been shown to interfere with the efficacy of antimalarial therapy for CLE. [34, 35] A meta-analysis from 2015 showed that smoking resulted in a two-fold decrease in the proportion of patients with CLE achieving cutaneous improvement with antimalarials. [36]

Vascular disorders

Buerger disease (thromboangiitis obliterans), a nonatherosclerotic segmental occlusive disease affecting multiple extremities, is associated strongly with cigarette smoking. It is most commonly seen in men aged 20-40 years who smoke heavily. Smoking cessation is the single most important therapeutic intervention in prevention of disease progression and morbidity. In continued smokers, at least 43% will require amputations. [37]

Dermatitis

Smoking has been shown to have a significant association with active hand eczema, especially in high-risk occupations. [38, 39] In occupational-related hand eczema, smoking increases severity, increases days missed from work, and confers a worse prognosis. [40]

Cigarettes are a known risk factor for allergic contact dermatitis. Numerous potential allergens from cigarettes can be found in filters, paper, and tobacco. [41] Dermatitis involving the hands, face, and neck should prompt patch testing in a smoker. In addition to standard patch test series, specific allergens such as cocoa, menthol, licorice, formaldehyde, and cigarette components should be used. [2] Several reports have documented irritant as well as allergic contact dermatitis to the nicotine patch in some patients attempting to quit smoking (see Irritant Contact Dermatitis and Allergic Contact Dermatitis).

Skin Cancer

Despite multiple carcinogens present in tobacco smoke, the relationship between smoking and skin cancer remains controversial. Two more other studies did not show an increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma in smokers. [42, 43] However, a separate meta-analysis showed a clear increased risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in smokers. [44] In addition, there appears to be a correlation between packs per day and smoking years with the development of squamous cell carcinoma, particularly in women. [45] Some evidence supports an increased risk of keratoacanthomas in smokers. [46] Overall, more studies need to be conducted to evaluate the role of smoking in the development of skin cancer.

No clear association has been proven between smoking and the development of basal cell carcinoma. [44] One study by Smith et al did find an increased prevalence between smoking and basal cell carcinoma tumors larger than 1 cm. [47]

No conclusive evidence exists that associates smoking with an increased risk of melanoma.

Smokers are at an increased risk of developing anogenital cancers. In a study evaluating anogenital cancer and smoking, the three sites most highly associated with smoking were the vulva, anus, and penis. [48]

Skin Conditions Improved with Smoking

Smoking appears to decrease the prevalence or lessen the severity of several skin diseases. More extensive research is needed to further evaluate these associations.

-

Aphthous stomatitis: This condition is less common in smokers than nonsmokers. Tobacco causes increased keratinization of oral mucosa, which may offer a protective effect. [49]

-

Pyoderma gangrenosum: Wolf et al has reported the successful treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum using nicotine patches. [52]

-

Pemphigus vulgaris: Mehta et al reported a man with pemphigus vulgaris whose disease flared when he quit smoking and improved when he returned to smoking. [53]

Conclusion

Skin is not exempt from the deleterious effects of smoking. Raising awareness of smoking related conditions and skin changes may provide incentive to patients to quit smoking. Knowledge of the cutaneous manifestations of smoking is important to aid clinicians in smoking prevention and cessation, reducing procedure complications, and lowering the occurrence and severity of smoking-related skin conditions.

-

Facial features consistent with "smoker's face" characterized by prominent facial rhytides, dyschromia, atrophic skin, and prominence of underlying bony contours.

-

Favre-Racouchot syndrome is a condition characterized by deep rhytides and comedone formation linked with smoking and solar damage.