Overview

Cardiovascular disorders and therapies are often associated with a variety of dermatologic manifestations. Frequently, these cutaneous signs can be used in facilitating a diagnosis of the underlying cardiac disease. For example, the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever in patients presenting with acute carditis includes 2 skin signs out of the 5 classic Jones criteria (ie, arthritis, carditis, erythema marginatum, subcutaneous nodules, and chorea). [1] Certain congenital cardiac defects are associated with unique skin manifestations, such as coarctation of the aorta associated with external features of Turner syndrome or atrioventricular (AV) septal defects associated with skin features of Down syndrome. In some patients, the dermatologic manifestations represent a component of a full systemic or vascular disorder that also involves defects in the cardiovascular system as another accompanying component.

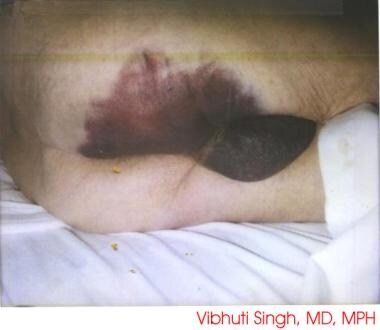

Advanced medical and invasive therapies have led to recognition of many new dermatologic manifestations, for example, angioedema from ACE inhibitors, ankle swelling due to calcium channel blockers, or radiation skin burns following prolonged angioplasty and radiation exposure. [2] Calcium channel blockers and ACE inhibitors have also been reported to cause drug-induced cutaneous lupus erythematosus. [3] The image below illustrates cutaneous bleeding in a patient on warfarin therapy for atrial fibrillation.

In this article, a discussion of some of the more common and clinically relevant dermatologic manifestations encountered in cardiac patients is reviewed, along with plausible differentials as applicable. Knowledge of many of the skin manifestations in the setting of cardiac diseases has become very important and is immensely helpful for proper diagnosis and treatment of patients with cardiovascular disorders.

For excellent patient education resources, visit eMedicineHealth's Heart Health Center and Cholesterol Center. Also, see eMedicineHealth's patient education articles Coronary Heart Disease, High Cholesterol, Cholesterol FAQs, and Atorvastatin (Lipitor).

The Medscape Heart Failure Resource Center may be of interest.

Dermatologic Manifestations in Primarily Cardiac Diseases

Clubbing (Hypertrophic Osteoarthropathy)

Definition

Clubbing represents a localized drumsticklike swelling of the distal segments of fingers and toes, particularly over the extensor surface. It is caused by connective tissue proliferation leading to increases in the sponginess of the soft tissue at the base of the nails due to stimulation by a humoral substance that causes dilation of the vessels of the fingertip or toe tip. [4]

Differential diagnosis

Clubbing, as illustrated below, is seen in persons with cyanotic congenital heart diseases (eg, tetralogy of Fallot, Eisenmenger syndrome). It is also seen in persons with infective endocarditis. The differential diagnosis may include hereditary, idiopathic, constitutional, or acquired conditions. The acquired causes include pulmonary conditions (ie, primary and metastatic lung cancer, bronchiectasis, lung abscess, cystic fibrosis, mesothelioma) or gastrointestinal diseases (ie, regional enteritis, ulcerative colitis, cirrhosis).

Schematic representation of clubbing of a finger in a patient with Eisenmenger syndrome (right-to-left shunt).

Schematic representation of clubbing of a finger in a patient with Eisenmenger syndrome (right-to-left shunt).

Cyanosis

Definition

Cyanosis is a bluish discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes due to an increased amount of reduced hemoglobin in the small blood vessels of the skin. It is most appreciable in the lips, nail beds, earlobes, and cheeks. The mechanism includes either dilatation of cutaneous venules or a reduction in the oxygen saturation of intracapillary blood. Cyanosis manifests when the absolute concentration of reduced hemoglobin exceeds 5 g/dL.

Clinical presentation

Cyanosis may be central or peripheral. In the central type, the desaturation of the arterial blood affects both the mucous membranes and the skin. In peripheral cyanosis, a slowing of blood flow and overextraction of oxygen from blood occurs as a result of vasoconstriction and reduced peripheral blood flow owing to cold exposure, shock, congestive heart failure (CHF), or peripheral vascular disease.

Central cyanosis is caused by the following:

-

Decrease in partial pressure of oxygen in the inspired air

-

Insufficient compensatory alveolar hyperventilation to maintain alveolar oxygen tension

-

A mutant hemoglobin with low affinity for oxygen (eg, hemoglobin-Kansas or Hb Kansas)

-

Serious pulmonary dysfunction (acutely, as in extensive pneumonia or pulmonary edema, or chronically, as in emphysema)

-

Shunting of systemic venous blood into the arterial system, as in certain forms of congenital heart disease causing right-to-left shunt (eg, tetralogy of Fallot, Eisenmenger syndrome)

-

Pulmonary arteriovenous fistulas (congenital or acquired, solitary or multiple, microscopic or massive)

-

Circulating methemoglobin or sulfhemoglobin (sought by spectroscopy)

Peripheral cyanosis generally results from the following:

-

Exposure to cold air or water (a normal response)

-

Low cardiac output states, as in severe CHF or shock (Cutaneous vasoconstriction occurs as a compensatory mechanism.)

-

Arterial obstruction to an extremity, as with an embolus

-

Arteriolar constriction, as in cold-induced vasospasm (Raynaud phenomenon)

-

Venous obstruction causing stagnation of blood flow

-

Venous hypertension, which may be local (as in thrombophlebitis) or generalized (as in tricuspid valve disease or constrictive pericarditis)

Differential cyanosis

Differential cyanosis occurs in patients with patent ductus arteriosus, pulmonary hypertension, and right-to-left shunt. Differential cyanosis is when cyanosis occurs in the lower but not in the upper extremities.

Mitral Facies

Mild cyanosis of the lips, cheeks, and malar prominences, without clubbing of the fingers, is often seen in patients with mitral stenosis. It results from slight arterial hypoxia due to fibrotic changes in the lungs that develop because of long-standing pulmonary congestion combined with low cardiac output.

Edema

Definition

Edema is defined as a clinically apparent increase in the interstitial fluid volume. A weight gain of several pounds over dry weight occurs before overt manifestations of edema. Edema may be localized or generalized (eg, edema involving the face, trunk, and extremities, termed anasarca). Edema may manifest as puffiness of the face (mainly in the periorbital areas) or as skin swelling that retains an indentation if pressed with a finger (ie, pitting edema). In the early stages, patients report that their rings fit more snugly on their fingers or they are having difficulty putting on shoes, particularly in the evening. The image below illustrates bilateral pitting edema in the lower extremities.

Pathogenesis

Starling forces

These forces regulate the exchange of fluid between the 2 components (vascular and extravascular) of the extracellular compartment. The hydrostatic pressure within the vessels and the colloid oncotic pressure in the interstitial fluid tend to move fluid out of the vessels to the extravascular space. On the other hand, the hydrostatic pressure within the interstitial fluid (tissue tension) and the colloid oncotic pressure within the vascular system (from plasma proteins) promote the movement of fluid into the vascular compartment. These forces are usually balanced. The development of edema depends on one or more changes in the Starling forces such that a net movement of fluid occurs from the vascular system into the interstitium.

Capillary damage

Edema also may result from damage to the capillary endothelium from chemical, bacterial, thermal, mechanical, or immunologic causes, leading to increased permeability and, thus, movement of protein into the interstitial compartment. The extravascular colloid oncotic pressure rises, causing net fluid movement outside of the vessels.

Reduction of effective arterial volume

Patients with reduced effective arterial blood volume respond by increasing salt retention and, therefore, water retention by the proximal tubule, which leads to edema. Causes include CHF, low cardiac output states, nephrotic syndrome, and cirrhosis. The condition is made worse by the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, which responds by acting on the efferent renal arterioles and increasing Na+ reabsorption in the proximal tubule. This system also operates locally. Both circulating and renally produced angiotensin II contribute to renal vasoconstriction and to salt and water retention. Arginine vasopressin and endothelin levels are also elevated in persons with CHF and contribute to renal vasoconstriction, Na+ retention, and edema. In contrast, the atrial natriuretic peptides increase glomerular filtration, inhibit sodium reabsorption in the proximal tubule, and inhibit release of renin and aldosterone, leading to a reduction in sodium retention.

Differential diagnosis

The 2 main cardiovascular causes include CHF and venous insufficiency. Usually, the edema is symmetrical over both ankles in patients with CHF. If CHF patients are bedridden, the edema appears over the sacral area. Edema of venous insufficiency may be associated with hyperpigmentation of the skin due to venous stasis. Ulceration may occur.

The differential diagnoses include the following:

-

Symmetric, dependent pitting edema in CHF or venous insufficiency

-

Asymmetric lower extremity swelling in deep venous thrombosis or postcoronary bypass (on the side from which the vein was harvested)

-

Generalized edema or anasarca in severe heart failure, cirrhosis, or nephrotic syndrome

-

Pretibial edema in myxedema (nonpitting), hypoproteinemia, hereditary angioneurotic edema, or acute glomerulonephritis

-

Upper body edema of the face, arms, and neck in superior vena cava syndrome (from lung mass)

-

Asymmetrical upper extremity edema in mastectomy or thrombophlebitis

-

Edema not associated with dyspnea, which may be due to tricuspid stenosis, constrictive pericarditis, or right atrial tumor

Management

Patients should reduce salt intake, rest in the supine position each day, and wear elastic stockings, which should be put on before arising in the morning. Diuretics are helpful initially. Medications, including ACE inhibitors, progesterone, the dopamine receptor agonist bromocriptine, and sympathomimetic amine dextroamphetamine may be useful when administered to patients with resistant edema.

Ascites

Definition

Ascites is characterized by a tensely distended abdomen with tightly stretched skin, bulging flanks, and everted umbilicus. It is often seen in patients with CHF, tricuspid valve disease, and constrictive pericarditis.

Clinical presentation

Abdominal distension may be noticed first by the patient in the form of a progressive increase in belt or dress size or the appearance of hernias. Progressive abdominal swelling may be associated with a sensation of pulling or stretching of the flanks or groins. Ask the patient with diffuse abdominal swelling about alcohol intake, a past history of jaundice or hematuria, or an alteration in bowel habits. Such historical information may help differentiate the usual causes (eg, cirrhosis, a colonic tumor involving the peritoneum, CHF, nephrosis).

Physical examination

The presence of peritoneal fluid (ascites) is indicated by demonstrating a percussion fluid wave and flank dullness that shifts with a change in position. In patients who are obese, small amounts of fluid may be difficult to demonstrate; on occasion, the fluid may be detected by abdominal percussion with patients on their hands and knees. Small amounts of ascites can often be detected only by ultrasound examination of the abdomen. An abdominal radiograph shows a ground-glass appearance, and a CT scan of the abdomen also may be helpful in the diagnosis. The evaluation of a patient with ascites requires that the cause of the ascites be established. In most cases, ascites appear as a part of a well-recognized illness (ie, cirrhosis, CHF, nephrosis, disseminated carcinomatosis).

Management

Abdominal paracentesis may be required to establish the diagnosis. Exudative ascites should initiate an evaluation for a primary peritoneal process, most importantly infection or tumor. Transudative ascites is frequently due to cirrhosis, right-sided venous hypertension raising the hepatic sinusoidal pressure, or hypoalbuminemic states (eg, nephrosis, protein-losing enteropathy). Strongly consider right-sided valvular diseases of the heart and, in particular, constrictive pericarditis. Establishing a diagnosis may require cardiac imaging and cardiac catheterization.

Pallor

Causes

Patients with a prosthetic metallic aortic valve may exhibit pallor because of the development of anemia from RBC destruction (and production of schistocytes). Pallor and anemia are also observed in those with bacterial endocarditis and in patients with acute coronary syndromes who develop blood loss following treatment with thrombolytic therapy, heparin, or powerful intravenous platelet-inhibiting agents.

Clinical presentation

Pallor, as shown below, of the skin and mucous membranes is loss of the normal red or pink hue when a drop in the hemoglobin level occurs to less than 8-10 g/dL. Pallor may be difficult to identify in patients with CHF or subcutaneous edema, low skin blood flow, or dark-colored skin. Focus the examination on areas where vessels are close to the surface (eg, mucous membranes of conjunctiva, inner surface of lower eyelids, nail beds, palmar creases of the hands).

Laboratory evaluation

A complete blood cell count, reticulocyte count, and measurements of serum iron, total iron-binding capacity, and serum ferritin are needed. In patients with severe anemia and abnormalities in RBC morphology, a bone marrow aspirate and biopsy may be required. In cases of increased RBC destruction or hemolysis, the anemia is easily identified from the increased reticulocyte count, along with normocytic RBC morphology. This indicates the capacity of the erythroid marrow to compensate for a blood loss with an increase in RBC production.

Management

Management begins at the time of assessment. When an anemia is severe enough to threaten survival, immediate steps must be taken to guarantee oxygen delivery to tissues through the appropriate infusion of electrolyte and colloid solutions and RBC transfusions along with supplemental oxygen, and essential vitamins or chemotherapeutic agent(s) should be administered to address a specific cause. In less severe anemia, withhold transfusions and other therapy until the diagnosis is established. The selection of the right therapy should be based on the documented cause. Often, more than one etiologic component must be addressed in management.

Baldness, Thoracic Hairiness, and Earlobe Crease

Baldness, short stature, thoracic hairiness, and diagonal earlobe crease are found in some patients with atherosclerosis. They have been associated with an increased incidence of coronary heart disease. The mechanism is unclear. Genetic abnormalities may be responsible. [5]

Diagonal earlobe crease

Reports based on coronary angiographic studies and postmortem examinations have shown a higher prevalence of diagonal earlobe creases in patients with coronary heart disease. The evidence to date indicates that this ear crease may be a cutaneous sign of coronary heart disease and, therefore, can be used to identify patients at an increased risk for coronary heart disease. [6, 7]

Baldness, thoracic hairiness, hair graying, and earlobe crease

A case-control study [8] examined the association of dermatological signs, such as baldness, thoracic hairiness, hair graying, and diagonal earlobe crease, with the risk of myocardial infarction in male subjects younger than 60 years. It included 842 male subjects admitted for the first nonfatal myocardial infarction; the controls were 712 male subjects admitted with noncardiac diagnoses, without clinical signs of coronary disease.

The relative risks were estimated as odds ratios. Logistic regression was used to control for the confounding variables. Baldness, thoracic hairiness, and earlobe crease were approximately 40% more prevalent in noncontrol subjects. After allowing for age and other established coronary risk factors, the relative risk of myocardial infarction for frontoparietal baldness compared with no hair loss was 1.77 (95% confidence interval 1.27-2.45) and it was 1.83 (95% confidence interval 1.4-2.3) for men with thick, extended thoracic hairiness. The presence of a diagonal earlobe crease yielded a relative risk of 1.37 (95% confidence interval 1.25-1.5), while hair graying was associated with myocardial infarction only in male subjects younger than 50 years.

The authors concluded that baldness, thoracic hairiness, and diagonal earlobe crease indicate an additional risk of myocardial infarction in men younger than 60 years, independent of age and other established coronary risk factors. In a report by Matilainen et al, [9] the presence of insulin resistance that increases coronary disease risk has been shown to be associated with an early onset of male-pattern baldness or alopecia. This may represent a common pathogenetic mechanism for baldness and coronary atherosclerosis.

Petechiae

Petechiae are found most frequently on the conjunctivae, palate, buccal mucosa, and upper extremities. They are found in persons with infective endocarditis.

Splinter Hemorrhages

Splinter hemorrhages are subungual, linear, dark-red streaks that may appear in persons with infective endocarditis.

Roth Spots

Roth spots are oval, retinal hemorrhages with a clear, pale center. Differential diagnoses include connective-tissue disease and severe anemia. They are noted in persons with infective endocarditis. [10]

Osler Nodes

Osler nodes are small, tender nodules that develop on the finger or toe pads in patients with infective endocarditis. They persist for hours to days.

Janeway Lesions

Janeway lesions are small hemorrhages with a slightly nodular appearance that occur on the palms and soles. They are most common in persons with acute infective endocarditis.

Peripheral Emboli

Embolic episodes are common in patients with infective endocarditis, and they may occur during or after therapy. Emboli to large arteries (eg, femoral arteries) are often the result of fungal endocarditis, with its large, friable vegetations. Pulmonary emboli are common in patients with history of drug abuse who develop right-sided endocarditis. They also may be seen in patients with left-sided endocarditis who have left-to-right cardiac shunts. Peripheral arterial septic emboli from valvular bacterial endocarditis are also seen. These may result in digital infarcts.

Definition and clinical presentation

Livedo reticularis is a dermatologic manifestation of atherosclerotic or cholesterol embolization in which localized areas of the extremities develop a mottled or netlike appearance of bluish-to-red discoloration. The mottled appearance becomes particularly more prominent upon exposure to cold. Atheroembolism is a form of acute arterial occlusion in which numerous small debris of fibrin, platelet, and cholesterol embolize distally from proximal atherosclerotic or aneurysmal sites. It may follow intra-arterial procedures. Because the emboli tend to lodge in the smallest vessels, distal pulses in the large vessels usually remain palpable. Patients present with acute pain and tenderness at the site of embolization.

Management

Vascular occlusion in the fingers and toes may result in ischemia (ie, blue toe syndrome). Digital necrosis and gangrene may develop. Skin or muscle biopsy findings may exhibit cholesterol crystals. Ischemia resulting from atheroemboli is difficult to treat because neither surgical revascularization nor thrombolysis is helpful because of their multiplicity, mixed composition, and distal location. Platelet inhibitors may prevent atheroembolism if given prior to the intra-arterial intervention. For recurrent embolization, surgical removal or bypass of the atherosclerotic vessel or aneurysm may be necessary.

Xanthomas and Xanthelasma

Eruptive xanthomas are the most common form of xanthomas, and they are associated with hypertriglyceridemia types I, III, IV, and V. They appear as crops of yellow-orange papules with erythematous halos on the extensor surfaces of the extremities and the buttocks. They usually appear when triglyceride levels are greater than 11 mmol/L (1000 mg/dL), ie, when chylomicronemia is present. At these high levels of triglycerides, the retinal vessels can appear orange-yellow (lipemia retinalis). They can spontaneously diminish with a fall in serum lipid levels.

Tendon, plane, and tuberous xanthomas

Increased beta-lipoprotein levels (primarily types II and III) may be associated with different types of xanthomas, including xanthelasma, tendon xanthomas, and plane xanthomas. Tendon xanthomas are frequently associated with the Achilles and extensor finger tendons. Plane xanthomas are flat and favor the palmar creases, face, upper trunk, and scars. Tuberous xanthomas are frequently associated with hypertriglyceridemia, but they are also seen in patients with type II hypercholesterolemia and are found most frequently over the large joints or hand. [11]

Xanthelasma Palpebrarum

Xanthelasma palpebrarum is found on the eyelids (see the image below).

On average, only half the patients with xanthelasma palpebrarum are hyperlipidemic; their risk for atherosclerosis may be inferred from the associated lipoprotein and apolipoprotein abnormalities. [12] Several studies show decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and other lipoprotein and apolipoprotein abnormalities that are associated with atherosclerosis. Therefore, based on present data, determining the plasma lipoprotein and apolipoprotein levels (especially those associated with an increased risk for atherosclerosis) in each patient with xanthelasma appears to be justified. [13, 14, 15]

Histology

Biopsy specimens of xanthomas show collections of lipid-containing macrophages (foam cells). The lipid compositions of 8 normolipidemic xanthelasma palpebrarum lesions were analyzed in a recent study using thin-layer chromatography, with the adjacent uninvolved skin used as a control. The lesions were found to be composed predominantly of cholesterol, mostly cholesterol ester, whereas phospholipids predominated in the control specimens.

Management

Probucol, bichloracetic acid, or cryotherapy [16] may be effective for eyelid xanthelasmas. The UltraPulse carbon dioxide laser also may be helpful. Excision with healing by secondary intention and microsurgical inverted peeling are surgical options.

Dermatologic Manifestations in Congenital Heart Diseases

Williams Syndrome (Elfin Facies and Supravalvular Aortic Stenosis)

Infants with supravalvular aortic stenosis syndrome (Williams syndrome) exhibit elfin facies. This is characterized by a high prominent forehead, stellate iris patterns, epicanthal folds, underdeveloped mandible and bridge of the nose, overhanging upper lip, strabismus, and dental abnormalities. The mechanism may include problems with regulation of circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D and with metabolism of calcitonin. These patients also may show intellectual disability, facial and skeletal defects, and narrowing of the peripheral and pulmonary arteries.

Marfan Syndrome (Long Extremities, Skin Striae, and Aortic Aneurysm)

Marfan syndrome is an inherited connective-tissue disorder transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait. [17] The patients with severe Marfan syndrome exhibit long, thin extremities with other skeletal changes, ocular lens dislocation (ectopia lentis), and aortic aneurysm. The severe form is caused by a mutation in a single allele of the fibrillin gene (FBN1). Typical facies include dolichocephaly, malar hypoplasia, and enophthalmos.

Molecular defects

Most patients are heterozygotes for mutations in a gene on chromosome 15 that encodes fibrillin, a 350-kd glycoprotein that is a major component of elastin-associated microfibrils. These microfibrils are abundant in large blood vessels and the suspensory ligaments of the lens. Approximately one third of the mutations cause premature termination of translation, and most of the remainder cause single amino acid substitutions in the epidermal growth factor–like domains of the molecule that may be involved in calcium binding.

Differential diagnosis

See the list below:

-

Homocystinuria, which causes ectopia lentis and similar skeletal defects

-

Congenital contractural arachnodactyly due to mutations in another fibrillin gene (FBN2)

-

Familial ectopia lentis

-

Familial aortic aneurysms that result from the autosomal dominant disorder, type IV Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

Clinical presentation

Its incidence is approximately 1 case in 10,000 persons, and it is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. A quarter of patients are affected as a result of new mutations.

Cardiovascular abnormalities are the major source of morbidity and mortality. These include mitral valve prolapse and dilatation of the root of the aorta and the sinuses of Valsalva, causing aortic regurgitation, dissection, and rupture.

With regard to skeletal features, patients are tall with a shorter upper segment (top of the head to top of the pubic ramus) than the lower segment (top of the pubic ramus to the floor). The ratio of these measurements is abnormal by 2 standard deviations. The fingers are long, slender, and spiderlike (arachnodactyly). Patients may have chest deformities (pectus excavatum, pectus carinatum), scoliosis, kyphosis, high-arched palate, and high pedal arches or pes planus.

Ocular features may include dislocation of the lens, myopia, retinal detachment, lattice degeneration, and retinal tears; however, most patients have adequate vision.

Other features are striae over the shoulders and buttocks and the development of spontaneous pneumothorax, inguinal hernias, and incisional hernias.

Management

The diagnosis can be established if the patient has dislocated lenses, aortic dilatation, and long and thin extremities along with kyphoscoliosis or other chest deformities (ie, Marfan habitus). All patients in whom the diagnosis is suggested should undergo a slit-lamp examination and an echocardiogram.

Marfan syndrome has no specific treatment. Propranolol or other beta-adrenergic blocking agents may delay or prevent aortic dilatation. Surgical replacement of the aorta, aortic valve, and mitral valve has been helpful in some patients. All patients should be monitored carefully with echocardiographic and clinical evaluations. Patients should be advised of the risks of severe physical and emotional stress and of pregnancy, all of which worsen the cardiovascular manifestations. Scoliosis can be treated by mechanical bracing and physical therapy if less than 20° or by surgery if it progresses to 20-45°. Dislocated lenses rarely require surgical removal, but patients must be monitored closely for retinal detachment.

Lutembacher Syndrome (Skin Signs of Acute Rheumatic Disease and Mitral Stenosis)

This syndrome encompasses a rare combination of atrial septal defect and mitral stenosis, which is almost always the result of acquired rheumatic valvulitis.

Down Syndrome (Trisomy 21) and Ellis-van Creveld Syndrome (Typical Facies or Ectodermal Dysplasia and AV Canal Defects)

Ellis-van Creveld syndrome includes ectodermal dysplasia and polydactyly. Down syndrome is characterized by typical moon facies. Both are associated with AV septal defects. AV septal defects account for 4-5% of congenital heart defects. Malformations are characterized by varying degrees of incomplete development of the lower portion of atrial septum, the inflow of the ventricular septum, and the AV valves (endocardial cushion defects and AV canal defects). The basic defect is a deficiency of the AV septum, which separates the left ventricular inflow from the right atrium. The anomalies range from a small ostium primum atrial defect to a complete AV malformation involving defects in the interventricular septum and the mitral and tricuspid valves. The common AV valve frequently is abnormal, with 5 or 6 leaflets of variable size.

DiGeorge Syndrome (Cyanosis and Congenital Heart Disease with Left-to-right Shunt; Aortic Arch Interruption, Truncus Arteriosus)

An association of aortic arch interruption is commonly seen with DiGeorge syndrome. Other features include cardiac, parathyroid, thymic, and facial anomalies. Thymic hypoplasia is accompanied by immunological and hypocalcemia problems. The major morbidity is severe CHF due to (1) left ventricular volume overload resulting from the left-to-right shunt and (2) pressure overload from systemic hypertension. Physical findings include cardiomegaly, a systolic ejection sound accompanied by a thrill, a loud single second heart sound, a harsh systolic murmur, a low-pitched middiastolic rumbling murmur, and bounding pulses. Facial dysmorphism; malformations of the limbs, kidneys, and intestines; atrophy or absence of the thymus gland; T-lymphocyte deficiency; and a propensity for infections also may be features of the clinical presentation.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (Skin Changes and Myocarditis and Heart Block)

Congenital heart block is observed in some infants born to mothers with systemic lupus erythematosus. This may be due to various factors, such as fetal myocarditis, idiopathic hemorrhage and necrosis involving conduction tissue, degeneration and fibrosis related in some instances to the transplacental passage of anti-Ro/ss-A antibody, and other immune complexes from mothers.

Neonatal lupus erythematosus and its dermatologic manifestations were reviewed by Neiman et al. [18] They studied 47 mothers (83% white) whose sera contained anti-SSA/Ro, anti-SSB/La, and/or anti-U1-ribonucleoprotein antibodies and their 57 infants (20 boys and 37 girls) diagnosed with cutaneous neonatal lupus erythematosus. The infants' rashes often followed ultraviolet light exposure; the mean age at detection was 6 weeks, and the mean duration was 17 weeks. All had facial involvement (periorbital region most common) followed by the scalp, trunk, extremities, neck, and intertriginous areas. In 37, the rash resolved without sequelae, 43% of which were untreated. A quarter had residual sequelae that included telangiectasia and dyspigmentation. Of 20 subsequent births, 7 children were healthy, 2 had congenital heart block only, 4 had congenital heart block and skin rash, and 7 had skin rash only.

They concluded that future pregnancies should be monitored by serial echocardiograms, given the substantial risk for heart block, and that the affected neonates should be observed for later development of heart disease.

Turner Syndrome (Features of Turner Syndrome and Aortic Coarctation)

Patients with Turner syndrome often show congenital cardiac abnormalities (eg, coarctation of aorta). Patients present with upper extremity hypertension. Early surgical repair in childhood is associated with 89% survival at 15 years and 83% survival at 25 years. Postoperative sequelae are common. Three principal postoperative sequelae include residual systolic hypertension despite the absence of a coarctation gradient, bicuspid aortic valve, and recoarctation.

Surgical resection with end-to-end anastomosis results in the lowest incidence of recoarctation. Balloon dilatation has been helpful in the treatment of recoarctation, but not of the native coarctation.

RAS/MAPK Pathway Disorders

The RAS/MAPK pathway plays an important role in signal transduction of extracellular stimuli. This pathway is important for cellular processes, and germline mutations can interfere with craniofacial, cardiac, ectodermal, hematopoietic, musculoskeletal, and central nervous defects. [19] Cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome, Costello syndrome, and Noonan syndrome are all due to germline mutations in this pathway that make these patients more likely to have congenital heart defects and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome is a congenital syndrome characterized by the presence of a unique facial appearance, the presence of intellectual disability, hyperkeratotic skin and hair abnormalities, and associated congenital heart defects. It may be indistinguishable from Noonan syndrome, which has a familial pattern and does not manifest hyperkeratotic skin lesions and abnormal hair. [20, 21]

Multisystem Diseases With Involvement of Skin and Heart

Many systemic diseases with concomitant cutaneous manifestations also involve the cardiovascular system. Such diseases are discussed in this section.

Rheumatic Fever

Characteristic eruptions as described by Jones (eg, erythema marginatum) and skin nodules may be associated with concomitant acute carditis with valvular disease and CHF. Erythema marginatum is seen primarily on the trunk. Lesions are pinkish red, flat to mildly elevated, and transient.

Kawasaki Disease

Kawasaki disease is an acute febrile vasculitis of childhood that can lead to coronary artery aneurysm if left untreated. [22] The classic diagnosis is based on the presence fever lasting longer than 5 days and 4 of 5 of the following clinical features: edema or reddening of palms and soles, polymorphous rash, oropharyngeal changes, bilateral and painless bulbar conjunctival injection, and acute nonpurulent cervical lymphadenopathy with a lymph node diameter greater than 1.5 cm. [23] First-line treatment includes intravenous immunoglobulin and high-dose aspirin. Recalcitrant cases have traditionally been treated with corticosteroids; however, more recent literature has demonstrated increased rates of coronary artery lesions in patients treated with corticosteroids. [24]

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus may be associated with myocarditis (heart block) and cutaneous lupus stigmata (see the image below).

Systemic lupus erythematosus with lupus anticoagulant has been linked to an increased prevalence of arterial thrombosis.

Neonatal Lupus Erythematosus

Neonatal lupus erythematosus is seen in infants born to mothers with anti-SSA/Ro, anti-SSB/La and/or anti-U1-ribonucleoprotein antibodies. Approximately 50% of mothers are asymptomatic at presentation of the infant. [18, 25] The most common manifestations are skin, hepatic, and cardiac involvement. Cutaneous findings, which typically appear in the first week of life, are similar to subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus with annular, erythematous, scaly plaques in facial central areas, frequently involving the periocular and perioral areas. [25] Patients should be evaluated for congenital heart block using serial echocardiograms. [18]

Amyloidosis

Cardiomyopathy (restrictive) and cutaneous manifestations of primary systemic amyloidosis may coexist. Primary systemic amyloidosis consists of immunoglobulin light chains that accumulate in tissue, resulting in organ dysfunction. Up to 40% of affected individuals have skin findings, which include nonpalpable purpura. Patients may also have macroglossia, alopecia, and waxy papules, nodules and plaques. [26] Cardiac involvement can include heart block, restrictive cardiomyopathy, and heart failure.

Thyroid Disease (Myxedema or Graves Disease)

Cardiomyopathy, supraventricular arrhythmias, or atrial fibrillation in persons with Graves disease can be associated with ocular proptosis.

Sarcoidosis

Skin manifestations, including nodules (erythema nodosum), may be associated with heart block or cardiomyopathy (see the image below). [27, 28]

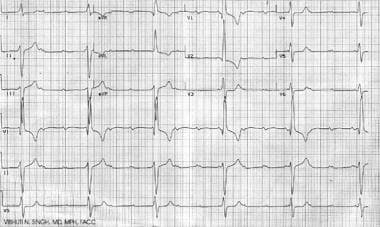

Heart block (second-degree Mobitz type II and third-degree heart block) in a patient with sarcoidosis.

Heart block (second-degree Mobitz type II and third-degree heart block) in a patient with sarcoidosis.

Syphilis

Aortitis and skin manifestations of secondary syphilis often coexist. In secondary syphilis, scattered red-brown papules with thin scaling are noted. The eruption often involves the palms and soles, and it can resemble pityriasis rosea. Associated findings that are helpful in making the diagnosis include annular plaques on the face, nonscarring alopecia, condyloma lata (broad-based and moist), mucous patches, lymphadenopathy, malaise, fever, headache, and myalgias. The interval between the primary chancre and the secondary stage is usually 4-8 weeks, and spontaneous resolution without appropriate therapy can occur.

Lyme Disease

Myocarditis can occur in 4-10% of patients infected with lyme disease. [29] Lyme disease, caused by Borrelia burgdorferi in the United States, begins with a characteristic skin lesion (erythema chronicum migrans). In the initial stage (3-30 d after tick bite), a single annular lesion is usually seen, which can spread to 10 cm in diameter. Within several days, approximately half the patients develop multiple, smaller, erythematous lesions at sites distant from the bite. Associated symptoms include fever, headache, myalgias, photophobia, arthralgias, and malar rash. If left untreated, Lyme disease can progress to stage II, in which systemic organ involvement occurs, including carditis. If recognized, Lyme carditis can be treated with antibiotics, and the cardiac conduction disturbances are generally reversible. [29]

Addison Disease (Hypoadrenalism)

Hypotension is found in patients with hyperpigmentation and other skin manifestations of hypoadrenalism (Addison disease). The form of hyperpigmentation seen with hypoadrenalism includes darkening of the skin, which may be of equal intensity over the entire body or it may be accentuated in sun-exposed areas. The differential diagnoses can be endocrine-, metabolism-, autoimmune-, or drug-related. The endocrinopathies that frequently have associated hyperpigmentation include Addison disease, Nelson syndrome, and ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome.

Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum

Mönckeberg sclerosis of the arteries is found in association with cutaneous features of pseudoxanthoma elasticum.

Sympathetic Dysautonomia

Patients present with myopathic facies and hypotension or syncope.

Acromegaly and Cushing Syndrome

These patients present with skin manifestations of acromegaly (gigantism) and Cushing disease. They develop hypertension and accelerated coronary artery disease.

Dermatomyositis

These patients present with dermatologic features of dermatomyositis. Rarely, they may also develop myocarditis.

Scleroderma

Patients with systemic sclerosis may develop pulmonary hypertension and pericarditis. [30] In scleroderma, the dilated blood vessels have a unique configuration and are known as mat telangiectasias. The lesions are wide macules measuring 2-7 mm in diameter; occasionally, they are larger, polygonal or oval, and uniformly red. The most common locations are the face, oral mucosa, and hands, ie, peripheral sites prone to intermittent ischemia.

The CREST (calcinosis cutis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility disorder, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia) syndrome variant of scleroderma is associated with a chronic course and anticentromere antibodies. Mat telangiectasias are also an important clue to the diagnosis of the CREST syndrome and systemic scleroderma. Hyperpigmentation can be seen in patients with scleroderma. It is accompanied by sclerosis of the extremities, face, and, less commonly, the trunk. Additional clues to the diagnosis of scleroderma are telangiectasias, calcinosis cutis, Raynaud phenomenon, and distal ulcerations.

Mucopolysaccharidosis (Hunter Disease)

Myocarditis and mitral valve involvement are often observed in patients with hepatosplenomegaly, kyphosis, joint disease, and contractures (mucopolysaccharidosis).

Dermatologic Manifestations of Primarily Vascular Diseases

Certain vascular disorders can involve skin and the cardiovascular system, including the following:

-

Arteritis and vasculitides

-

Hair loss and skin changes in patients with Buerger disease

-

Peripheral cyanosis in patients with Raynaud disease

-

Coronary artery inflammation in patients with giant cell arteritis and Kawasaki disease

-

Stasis ulcers in patients with varicose veins (see the image below)

-

Asymmetric leg swelling in deep venous thrombosis

-

Livedo reticularis from such entities as cholesterollike embolization

Arteriovenous Malformations

Patients born with high-flow arteriovenous malformations can develop hemorrhage, pain, and even high-flow congestive heart failure. There are multiple treatment options, including surgery and embolization. [31]

Dermatologic Manifestations Due to Cardiac Therapeutics

Therapeutic interventions often result in adverse skin effects and complications. Some of these are mentioned below:

-

Drug rashes are often seen with the use of penicillins and sulfa drugs for treatment of syphilis, rheumatic fever, and other described infections with cardiac manifestations.

-

Quinidine used for treatment of arrhythmias may cause thrombocytopenic purpura.

-

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia can cause petechiae.

-

Sites of subcutaneous injections of low molecular weight heparins show ecchymoses.

-

Use of calcium blockers and ACE inhibitors may lead to edema.

-

Amiodarone can cause thyroid changes and secondary skin manifestations. Diffuse hyperpigmentation due to drugs or metals can result from one of several mechanisms (eg, induction of melanin pigment formation, complexing of the drug or its metabolites to melanin, deposits of the drug in the dermis). Administration of amiodarone can result in both a phototoxic eruption (exaggerated sunburn) and/or a brown or blue-gray discoloration of sun-exposed skin. Biopsy specimens of the latter show yellow-brown granules in dermal macrophages, which represent intralysosomal accumulations of lipids, amiodarone, and its metabolites.

-

Prolonged radiation exposure in the cardiac catheterization laboratory (during angioplasty or ablations) may lead to fluoroscopic-induced chronic radiation dermatitis, typically over the right scapula. These lesions can appear days to months after preceeding cardiac catheterization and tend to persist. [32]

-

Thrombolytic therapy can cause localized cutaneous necrosis.

-

Spironolactone may cause gynecomastia.

-

Artificial heart valves can cause hemolysis and related anemia or jaundice.

-

Implanted pacemakers or defibrillators cause obvious skin swelling, as shown below, and their presence may be complicated by cutaneous erosion or sepsis.

-

Keloid formation is possible over midsternal scars after coronary bypass procedures.

-

Benign atheroembolic syndrome may occur secondary to systemic fibrinolysis with streptokinase. [33]

-

Livedo reticularis can develop from the use of streptokinase.

-

Administration of warfarin can cause painful areas of erythema that may become purpuric and necrotic with a black eschar. This is more common in women and in areas with abundant subcutaneous fat (eg, breasts, abdomen, buttocks, thighs, calves). The erythema and purpura develop 3-10 days after the onset of therapy. This may be a result of an imbalance in the levels of anticoagulant and procoagulant vitamin K–dependent factors. Continued therapy does not exacerbate preexisting lesions; patients with an inherited or acquired deficiency of protein C are at increased risk for this particular reaction and for purpura fulminans.

-

Ecchymosis, as shown below, may result following anticoagulation with the intravenous glycoprotein IIa/IIIa inhibitor, abciximab, during angioplasty and stenting of the coronary artery.

Summary

Many dermatologic manifestations are found in patients with cardiovascular disease that are either directly or indirectly related to the cardiac involvement or are due to cardiovascular therapeutic interventions. Often, such skin changes assume great importance in making a diagnosis or predicting prognosis.

The diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever in patients presenting with acute carditis includes the presence of erythema marginatum and subcutaneous nodules. Patients presenting with Marfan syndrome may have aortic aneurysm, mitral valve prolapse, tall habitus, arachnodactyly, and a high-arched palate. Many congenital cardiac disorders are associated with unique cutaneous manifestations as part of well-defined syndromes (eg, coarctation of the aorta in patients with external features of Turner syndrome, AV septal defects in patients with Down syndrome). The dermatologic manifestations frequently represent a systemic or vascular disorder that also involves the cardiovascular system.

Furthermore, the institution of medical and surgical or invasive therapies has led to the development of numerous new cutaneous signs, such as angioedema from ACE inhibitors, ankle swelling from calcium channel blockers, and radiation skin burns following prolonged angioplasty or radiographic procedures, just to name a few.

The knowledge of various dermatologic manifestations associated with cardiovascular disorders has the potential to be of tremendous help in making diagnoses and in predicting and recognizing complications associated with the ever-increasing armamentarium of pharmacologic and device therapies.

-

Xanthelasma palpebrarum in a patient with familial hypercholesterolemia.

-

Heart block (second-degree Mobitz type II and third-degree heart block) in a patient with sarcoidosis.

-

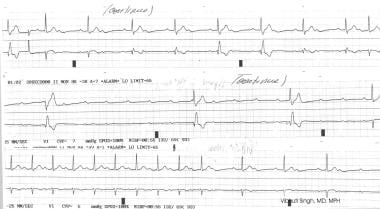

Complete heart block as seen in a patient with neonatal lupus erythematosus.

-

Bilateral pitting edema in a patient with congestive heart failure.

-

Schematic representation of clubbing of a finger in a patient with Eisenmenger syndrome (right-to-left shunt).

-

Ecchymosis following intravenous anticoagulation with the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, abciximab, during angioplasty and stenting of the coronary artery.

-

Dermatologic manifestations of cardiac disease. Sternotomy scar following bypass surgery.

-

Pallor seen in a patient with anemia due to erythrocyte damage from a prosthetic aortic valve.

-

Cutaneous bleeding in a patient on warfarin (Coumadin) therapy for atrial fibrillation.

-

Patient showing pacemaker swelling under the left subclavicular region. He also has a midsternal bypass graft scar.

-

Varicose veins and venous stasis with skin discoloration.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Dermatologic Manifestations in Primarily Cardiac Diseases

- Dermatologic Manifestations in Congenital Heart Diseases

- Multisystem Diseases With Involvement of Skin and Heart

- Dermatologic Manifestations of Primarily Vascular Diseases

- Dermatologic Manifestations Due to Cardiac Therapeutics

- Summary

- Show All

- Media Gallery

- References