Overview

The dermatologic manifestations of either toxic epidermal necrolysis or Stevens-Johnson syndrome may constitute a true emergency. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis are thought to be a single disease entity with common causes and mechanisms that is a severe cutaneous adverse reaction differentiated by the severity and extent of skin detachment. [1]

Toxic epidermal necrolysis, an acute disorder, is characterized by widespread erythematous macules and targetoid lesions; full-thickness epidermal necrosis, at least focally; and involvement of more than 30% of the cutaneous surface. Commonly, the mucous membranes are also involved. Nearly all cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis are induced by medications, and the mortality rate can approach 40%. [2]

Manifestations of Stevens-Johnson syndrome include purpuric macules and targetoid lesions; full-thickness epidermal necrosis, although with lesser detachment of the cutaneous surface; and mucous membrane involvement. As with toxic epidermal necrolysis, medications are important inciting agents. If medications are the offending agent, symptoms may present within 4-28 days after exposure. In some cases, Mycoplasma infections may induce Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermolysis syndrome, although it may present atypically with no skin lesions and only mucosal involvement, which is known as Fuchs syndrome. [3] The mortality rate associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome is much lower than the rate associated with toxic epidermal necrolysis, approaching 5% of cases.

The prognosis in these diseases is largely a function of the degree of skin sloughing. As the percentage of skin sloughing increases, the mortality rate dramatically worsens. For unknown reasons, however, the disease process in some patients simply stops progressing, and rapid epithelialization ensues. For patients experiencing sloughing over a large area of their skin surface, the mortality rate is much higher. In comparing mortality between adults and children, the mortality rate in children is much lower than in adults. [4]

See the images below.

Together, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis may represent a spectrum of a single disease process. Stevens-Johnson syndrome may also have features of the dermatologic condition erythema multiforme (which has led to confusion in nosology).

Treatment

Treatment mainly consists of supportive and symptom-targeted care, with early transfer to and care in a burn unit for a demonstrated decrease in mortality. [1] Coupled with early withdrawal of offending agents, supportive care is the best treatment that can be offered. [5, 6] Another consideration in treatment is the prevention of long-term sequelae, which are significant causes of morbidity. Aspects of supportive care to consider are infection prevention, sedation and pain management, and psychological support. [1]

Patient History and Physical Examination

Constitutional symptoms, such as fever, anorexia, malaise, myalgias, cough, or sore throat, may appear 1-3 days prior to any cutaneous lesions. Patients may report a burning sensation in their eyes, photophobia, and a burning rash that begins symmetrically on the face and the upper part of the torso. Ocular symptoms present as the initial symptom in up to 45% of cases. [7] Delineation of a drug exposure timeline is essential, especially in the 1-3 weeks preceding the cutaneous eruption.

Primary lesions

The initial skin lesions of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis are poorly defined, erythematous macules with darker, purpuric centers. The lesions differ from classic target lesions of erythema multiforme by having only two zones of color: a central, dusky purpura or a central bulla, with a surrounding macular erythema. A classic target lesion has three zones of color: a central, dusky purpura or a central bulla; a surrounding pale, edematous zone; and a surrounding macular erythema. See the image below.

Lesions, with the exception of central bullae, are typically flat. (Lesions of erythema multiforme are more likely to be palpable.) Less frequently, the initial eruption may be scarlatiniform. See the image below.

Nondenuded areas have a wrinkled paper appearance. A Nikolsky sign is easily demonstrated by applying lateral pressure to a bulla. With regard to the arrangement of lesions, individual macules are found surrounding large areas of confluence. See the image below.

Distribution

Lesions begin symmetrically on the face and the upper part of the torso and extend rapidly, with maximal extension in 2-3 days. In some cases, maximal extension can occur rapidly over hours. Lesions may predominate in sun-exposed areas.

Full detachment is more likely to occur in areas subjected to pressure, such as the shoulders, the sacrum, or the buttocks. Painful, edematous erythema may appear on the palms and the soles. The hairy scalp typically remains intact, but the entire epidermis, including the nail beds, may be affected. See the image below.

Sheetlike desquamation on the foot in a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis. Courtesy of Robert Schwartz, MD.

Sheetlike desquamation on the foot in a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis. Courtesy of Robert Schwartz, MD.

A classification proposes that epidermal detachment in Stevens-Johnson syndrome is limited to less than 10% of the body surface area (BSA). Overlapping Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis has more extensive confluence of erythematous and purpuric macules, leading to epidermal detachment of 10-30% of the BSA. Classic toxic epidermal necrolysis has epidermal detachment of more than 30%.

An uncommon form of toxic epidermal necrolysis (toxic epidermal necrolysis without spots) lacks targetoid lesions, and blisters form on confluent erythema. Greater than 10% epidermal detachment is required for diagnosis of these cases.

In contrast, bullous erythema multiforme, which was previously grouped with Stevens-Johnson syndrome, may have epidermal detachment of less than 10% of the BSA, but typical target lesions or raised atypical targets are localized primarily in an acral distribution.

Areas of denuded epidermis in Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis are dark red with an oozing surface. Mucous membrane involvement is present in nearly all patients and may precede skin lesions, appearing during the prodrome.

Complications

Cutaneous

Cutaneous complications are the most common sequelae of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis and can affect 23-100% of these patients. [8]

Cutaneous complications can include the following:

-

Postinflammatory dyspigmentation (hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation)

-

Abnormal scarring

-

Eruptive nevi

-

Nail changes (onychomadesis, anonychia, pterygium formation, ridging, dystrophy, abnormal pigmentation)

-

Telogen effluvium

-

Alopecia areata

-

Chronic pruritus

-

Hyperhidrosis

-

Photosensitivity

-

Heterotopic ossification

-

Disseminated ectopic sebaceous glands

A 2017 article in the American Journal of Dermatopathology discussed the presence of pseudomelanomas in a young man who developed Stevens-Johnson syndrome. [9] Preexisting nevi prior to his illness were examined and none was deemed atypical. Several months after his discharge, three of his nevi clinically had changed and biopsy revealed a pseudomelanoma phenomenon in each nevus.

Ocular

Keratitis may be the only initial presenting symptom; thus, a careful review of the patient’s history is essential. Ocular lesions are especially problematic because they have a high risk of sequelae. [7] In 20-75% of patients, chronic ocular sequelae can occur and are considered the most disabling. The chronic ophthalmic sequelae occur from multiple pathogenic processes and can lead to vision impairment and loss. [8]

Ocular complications can include the following:

-

Ectropion/entropion formation

-

Trichiasis, districhiasis

-

Dry eyes

-

Lagophthalmos

-

Corneal erosions

-

Corneal ulcerations

-

Corneal thinning

-

Neovascularization

-

Keratinization

-

Infectious keratitis

-

Chronic photosensitivity

Oral and dental

Painful oral erosions cause severe crusting of the lips, increased salivation, and impaired alimentation. Complete mucosal healing can occur in up to 75% of patients, but oral complications can occur. [8]

Oral complications can include the following:

-

Synechiae formation at angle of lips, between the tongue and floor of the mouth, and between gingival surfaces

-

Chronic ulcers

-

Depapillation of the tongue

-

Sjögren-like sicca syndrome

The main risk factor for developing complications is the severity of the mucosal involvement in the acute phase. Long-term buccal complications can ultimately affect mouth mobility, impairing speech and feeding. [8]

Dental complications are mainly reported in pediatric patients and include dental agenesis, root dysmorphia, short root, microdontia, and incomplete root apex closure. These dental sequelae can cause limitations in mastication and predisposition to dental caries. [8]

Pulmonary

Respiratory involvement can occur in up to 40% of patients. [8]

Pulmonary complications can include the following:

-

Epidermal sloughing of the bronchial epithelium

-

Pulmonary edema

-

Atelectasis

-

Infective pneumonitis

-

Bronchiolitis obliterans

-

Interstitial lung disease

-

Respiratory tract obstruction

-

Bronchiectasis

-

Bronchitis

Urogenital/gynecological

Chronic lesions of urogenital tract are less common than at other mucosal sites, with the most common complication being adhesions. Complications of the urogenital tract can also cause painful micturition. [8]

Gastrointestinal and hepatic

Acutely, patients may develop a profuse, protein-rich diarrhea. Gastrointestinal chronic sequelae are rare. [8]

Gastrointestinal and hepatic complications can include the following:

-

Esophageal strictures

-

Chronic intestinal ulcers

-

Vanishing bile duct syndrome (VBDS)

Renal

In approximately 20% of cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis, there have been reports of acute kidney injuries, with proteinuria also being common. Chronic renal insufficiency has been reported in some cases following Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis, but it is uncertain if it is a true sequela. [8]

Psychiatric and psychosocial

Long-term psychiatric and psychosocial complications remain unclear. It is recommended that these sequelae become a research priority. [8]

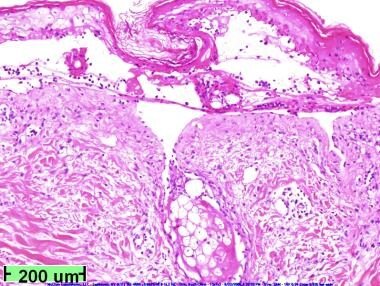

Histopathology

Flaccid blisters are typically present with full-thickness epidermal necrosis, as shown in the slide below.

Frozen sections usually show apoptotic keratinocytes throughout the entire epidermal layer, with lymphocytes and neutrophils in the epidermis. Separation of the epidermis from the dermis is apparent.

Another useful tool for that can be predictive of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis and may be used for early diagnosis is a rapid immunochromatographic test for serum granulysin. [10]

Pharmacologic Therapy

Corticosteroid therapy

The use of corticosteroids in the management of the Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis spectrum is controversial; most publications about their use are case reports and case series. Administration early in the course of disease has been advocated, but multiple retrospective studies demonstrate no benefit or higher rates of morbidity and mortality related to sepsis. This risk is probably proportional to the area of sloughed skin. Corticosteroids are associated with an increased rate of infections, delay of reepithelialization, and prolonged hospital stay durations. [10]

According to the EuroSCAR (European Study of Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions) study, systemic corticosteroids were associated with clinical benefit. Systemic corticosteroids were reported to be the most common treatment for Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in a survey of 50 drug hypersensitivity experts from 20 countries. One of the suggested protocols is intravenous dexamethasone 1.5 mg/kg pulse therapy (given for 30-60 min) for three consecutive days. [10]

Intravenous immunoglobulin

The use of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) has been studied in the treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis with mixed results. Viard et al suggested that keratinocyte apoptotic cell death occurs via activation of a cell-surface death receptor by Fas ligand (FasL). [11] In vitro, target cell death was blocked by a receptor-ligand blocking antibody and by antibodies present in pooled human IVIG. An open trial of IVIG in 10 patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis resulted in a halt of progression within 24-48 hours, with no mortality. Subsequent studies in the early 2000s would substantiate this benefit. A review by French et al in 2006 highlighted eight studies, six of which demonstrated a benefit for IVIG. [12] Analysis suggested a possible dose dependence with a trend towards a benefit for IVIG at doses larger than 2 g/kg on the mortality of toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Further analysis, however, has brought into question the proposed therapeutic mechanism and clinical benefit of IVIG therapy. An in vitro study suggested granulysin, not FasL, is the key cytotoxic molecule leading to keratinocyte cell death, raising the possibility of a new therapeutic target. [13] Clinical studies have also shown mixed benefit. In 2012, Huang et al performed a meta-analysis of 17 clinical studies containing at least eight patients to assess the efficacy of IVIG in toxic epidermal necrolysis. [14] While 12 of 17 of these studies concluded IVIG was effective in the treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis, meta-analysis did not support a clinical benefit of IVIG. However, this analysis did suggest high-dose IVIG exhibited a trend towards improved mortality. A subsequent meta-analysis in 2015 by Barron supported a decrease in mortality at IVIG doses greater than 2 g/kg. [15] While these analyses support a dose-dependent benefit, it should be noted that conflicting data regarding dose dependence exist, including a retrospective, noncontrolled study of 64 patients treated with IVIG, which demonstrated no mortality benefit between patients receiving high- (>3 g/kg) or low-dose (< 3 g/kg) IVIG. [16]

Given the potentially fatal nature of toxic epidermal necrolysis and the ethical issues involved, a randomized, controlled trial will likely never be performed. Given the suggestion of a therapeutic benefit, many centers are incorporating IVIG into their treatment protocols.

Cyclosporine

An open study from the trauma literature demonstrated the efficacy of cyclosporine in the treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Arevalo et al presented 11 patients admitted consecutively to a burn unit, with toxic epidermal necrolysis involving a large BSA (83% ± 17%). [17] Each patient received 3 mg/kg of cyclosporine daily, with the drug administered enterally every 12 hours. This group was compared to a series of six historical control subjects treated with cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids. In the study, the time from the onset of skin signs to arrest of disease progression and to complete reepithelialization was significantly shorter in the cyclosporine group. All patients in the cyclosporine group survived versus 50% surviving in the cyclophosphamide group.

An open-label phase II trial of adults and a retrospective chart review of patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis treated with cyclosporine have also demonstrated a decrease in death and the progression of detachment in adults. [1, 18]

Given a mortality rate of approximately 30% in patients not infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) with toxic epidermal necrolysis, cyclosporine may prove to be a life-saving therapy, but randomized, controlled trials are needed to make definitive recommendations.

Other medications

The tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)‒blocking agent etanercept has demonstrated promising results in case reports and a case series. A single subcutaneous injection of 50 mg of etanercept was administered to 10 patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis, resulting in prompt response in all patients with a median time to healing of 8.5 days. [19]

Cyclophosphamide, N-acetylcysteine, and monoclonal antibodies directed against cytokines have been used in isolated case reports and in small, uncontrolled studies. Thalidomide has been shown to have a deleterious effect on patients' outcomes. [20]

Other Therapies

Wound care

Currently there are no clinical guidelines for wound care and skin care of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Current treatments for erosions include chlorhexidine, octenisept, or polyhexanide solutions that are covered with nonadherent mesh gauze. A 2018 systematic review using the strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT) criteria was used to assess the effects of dressings to aid the clinician in deciding on the best wound care approach. [21]

Dressings can be divided into simple and modern dressings. Topical ointments or creams covered with bandages are classified as simple. Modern dressings include synthetic (Biobrane, Suprathel), biologic (xenografts, allografts), and fiber (nanocrystalline silver, Aquacel, Veloderm, Alginate Fiber) dressings and were found to be more commonly used, especially biologic dressings and silver impregnated (fiber) dressings. [21]

The systematic review concluded that modern dressings should be part of standard therapy over simple dressings, as they were shown to require fewer changes and caused less discomfort to the patients. [21]

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation changes are common and affect most Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis patients. It has been recommended that when an “anti-shear approach is undertaken and the detached skin is left in-situ” that the postinflammatory hyperpigmentation appears less severe. [22]

-

Note early cutaneous slough with areas of violaceous erythema.

-

Extensive sloughing on the face.

-

Note the presence of both 2-zoned atypical targetoid lesions and bullae.

-

Extensive blistering and sloughing on the back.

-

Extensive sloughing on the back.

-

Sheetlike desquamation on the foot in a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis. Courtesy of Robert Schwartz, MD.

-

Note extensive sloughing.

-

Low-power view showing full-thickness epidermal necrosis.