Practice Essentials

Alopecia areata is a recurrent nonscarring type of hair loss that can affect any hair-bearing area and can manifest in many different patterns. Although it is a benign condition and most patients are asymptomatic, it can cause emotional and psychosocial distress. See the images below.

Signs and symptoms

Alopecia areata most often is asymptomatic, but some patients (14%) experience a burning sensation or pruritus in the affected area. The condition usually is localized when it first appears, as follows:

-

Single patch - 80%

-

Two patches - 2.5%

-

Multiple patches - 7.7%

No correlation exists between the number of patches at onset and subsequent severity.

Alopecia areata can affect any hair-bearing area, and more than one area can be affected at once. Frequency of involvement at particular sites is as follows:

-

Scalp - 66.8-95%

-

Beard - 28% of males

-

Eyebrows - 3.8%

-

Extremities - 1.3%

Associated conditions may include the following:

-

Atopic dermatitis

-

Vitiligo

-

Thyroid disease

-

Collagen-vascular diseases

-

Down syndrome

-

Psychiatric disorders - Anxiety, personality disorders, depression, and paranoid disorders

-

Stressful life events in the 6 months before onset

Alopecia areata can be classified according to its pattern, as follows:

-

Reticular - Hair loss is more extensive and the patches coalesce

-

Ophiasis - Hair loss is localized to the sides and lower back of the scalp

-

Sisaipho (ophiasis spelled backwards) - Hair loss spares the sides and back of the head

-

Alopecia totalis - 100% hair loss on the scalp

-

Alopecia universalis - Complete loss of hair on all hair-bearing areas

Nail involvement, predominantly of the fingernails, is found in 6.8-49.4% of patients, most commonly in severe cases. Pitting is the most common; other reported abnormalities have included trachyonychia, Beau lines, onychorrhexis, onychomadesis, koilonychias, leukonychia, and red lunulae

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis usually can be made on clinical grounds. A scalp biopsy seldom is needed, but it can be helpful when the clinical diagnosis is less certain.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Treatment is not mandatory, because the condition is benign, and spontaneous remissions and recurrences are common. Treatment can be topical or systemic. [1]

Corticosteroids

Intralesional corticosteroid therapy is usually the treatment with the best response rate. The administration is as follows:

-

Injections are administered subcutaneously (can be intradermal) using a 3-mL syringe and a 30-gauge needle

-

Triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog) is used most commonly; concentrations vary from 2.5-10 mg/mL with similar efficacy

-

The lowest concentration is used on the face

-

Less than 0.1 mL is injected per site, and injections are spread out to cover the affected areas (approximately 1 cm between injection sites)

-

Injections are administered every 4-6 weeks

Topical corticosteroid therapy can be useful, especially in children who cannot tolerate injections. It is administered as follows:

-

Fluocinolone acetonide cream 0.2% (Synalar HP) twice daily or betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05% (Diprosone) has been used

-

For refractory alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis, 2.5 g of clobetasol propionate under occlusion with a plastic film 6 days/wk for 6 months helped a minority of patients

-

Treatment must be continued for a minimum of 3 months before regrowth can be expected, and maintenance therapy often is necessary

Systemic corticosteroids (ie, prednisone) are not an agent of choice for alopecia areata because of the adverse effects associated with both short- and long-term treatment. Some patients may experience initial benefit, but most patients relapse during cortisone tapering or after discontinuation of therapy, and ongoing therapy is often needed to maintain cosmetic growth, with a higher risk of adverse effects.

Immunotherapy

-

Topical immunotherapy [4] is defined as the induction and periodic elicitation of allergic contact dermatitis by topical application of potent contact allergens

-

Commonly used agents include squaric acid dibutylester (SADBE) and diphencyprone (DPCP) [5]

Anthralin

-

Both short-contact and overnight treatments have been used

-

Anthralin concentrations varied from 0.2-1%

Minoxidil

-

Minoxidil may be effective for patchy alopecia areata, but is of little benefit in alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis

-

The 5% solution appears to be more effective

-

No more than 25 drops are applied twice per day regardless of the extent of the affected area

-

Initial regrowth can be seen within 12 weeks, but continued application is needed to achieve cosmetically acceptable regrowth

Psoralen plus UV-A

-

Both systemic and topical PUVA therapies have been used

-

20-40 treatments usually are sufficient in most cases

-

Most patients relapse within a few months (mean, 4-8 months) after treatment is stopped

Other agents

-

Topical cyclosporine has shown limited efficacy

-

Topical tacrolimus

-

Systemic cyclosporine, like systemic corticosteroids, offer initial regrowth, but therapy must be continued to maintain efficacy, with a significant risk of adverse events

-

A randomized, double-blind study showed that both positive and negative results have been published with dupilumab; there have also been reports of cases of alopecia areata occurring during treatment with dupilumab

Cosmetic treatment

-

Dermatography has been used to camouflage the eyebrows of patients with alopecia areata; on average, 2-3 sessions lasting 1 hour each were required for each patient

-

Hairpieces are useful for patients with extensive disease

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Alopecia areata is a recurrent nonscarring type of hair loss that can affect any hair-bearing area. Clinically, alopecia areata can manifest many different patterns. Although medically benign, alopecia areata can cause tremendous emotional and psychosocial distress in affected patients and their families.

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology of alopecia areata remains unknown. The most widely accepted hypothesis is that alopecia areata is a T-cell–mediated autoimmune condition that is most likely to occur in genetically predisposed individuals. [8]

Autoimmunity

Much evidence supports the hypothesis that alopecia areata is an autoimmune condition. The process appears to be T-cell mediated, but antibodies directed to hair follicle structures also have been found with increased frequency in alopecia areata patients compared with control subjects. Using immunofluorescence, antibodies to anagen-phase hair follicles were found in as many as 90% of patients with alopecia areata compared with less than 37% of control subjects. The autoantibody response is heterogeneous and targets multiple structures of the anagen-phase hair follicle. The outer root sheath is the structure targeted most frequently, followed by the inner root sheath, the matrix, and the hair shaft. Whether these antibodies play a direct role in the pathogenesis or whether they are an epiphenomenon is not known.

Histologically, lesional biopsy findings of alopecia areata show a perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate around anagen-phase hair follicles. The infiltrate consists mostly of T-helper cells and, to a lesser extent, T-suppressor cells. CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes likely play a prominent role because the depletion of these T-cell subtypes results in complete or partial regrowth of hair in the Dundee experimental bald rat (DEBR) model of alopecia areata. The animals subsequently lose hair again once the T-cell population is replete. The fact that not all animals experience complete regrowth suggests that other mechanisms likely are involved. Total numbers of circulating T lymphocytes have been reported at both decreased and normal levels.

Studies in humans also reinforce the hypothesis of autoimmunity. Studies have shown that hair regrows when affected scalp is transplanted onto SCID (severe combined immunodeficiency) mice that are devoid of immune cells. Autologous T lymphocytes isolated from an affected scalp were cultured with hair follicle homogenates and autologous antigen-presenting cells. Following initial regrowth, injection of the T lymphocytes into the grafts resulted in loss of regrown hairs. Injections of autologous T lymphocytes that were not cultured with follicle homogenates did not trigger hair loss.

A similar experiment on nude (congenitally athymic) mice failed to trigger hair loss in regrown patches of alopecia areata after serum from affected patients was injected intravenously into the mice. However, the same study showed that mice injected with alopecia areata serum showed an increased deposition of immunoglobulin and complement in hair follicles of both grafted and nongrafted skin compared with mice injected with control serum, which showed no deposition.

In addition, research has shown that alopecia areata can be induced using transfer of grafts from alopecia areata–affected mice onto normal mice. Transfer of grafts from normal mice to alopecia areata–affected mice similarly resulted in hair loss in the grafts.

Clinical evidence favoring autoimmunity suggests that alopecia areata is associated with other autoimmune conditions, the most significant of which are thyroid diseases and vitiligo (see History). For instance, in a retrospective cross-sectional review of 2115 patients with alopecia areata who presented to academic medical centers in Boston over an 11-year period, comorbid autoimmune diagnoses included thyroid disease (14.6%), diabetes mellitus (11.1%), inflammatory bowel disease (6.3%), systemic lupus erythematosus (4.3%), rheumatoid arthritis(3.9%), and psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (2.0%). Other comorbid conditions found included atopy (allergic rhinitis, asthma, and/or eczema; 38.2%), contact dermatitis and other eczema (35.9%), mental health problems (depression or anxiety; 25.5%), hyperlipidemia (24.5%), hypertension (21.9%), and GERD (17.3%). [9, 10]

In conclusion, the beneficial effect of T-cell subtype depletion on hair growth, the detection of autoantibodies, the ability to transfer alopecia areata from affected animals to nonaffected animals, and the induction of remission by grafting affected areas onto immunosuppressed animals are evidence in favor of an autoimmune phenomenon. Certain factors within the hair follicles, and possibly in the surrounding milieu, trigger an autoimmune reaction. Some evidence suggests a melanocytic target within the hair follicle. Adding or subtracting immunologic factors profoundly modifies the outcome of hair growth.

Genetics

Many factors favor a genetic predisposition for alopecia areata. The frequency of positive family history for alopecia areata in affected patients has been estimated to be 10-20% compared with 1.7% in control subjects. [8] The incidence is higher in patients with more severe disease (16-18%) compared with patients with localized alopecia areata (7-13%). Reports of alopecia areata occurring in twins also are of interest. No correlation has been found between the degree of involvement of alopecia areata and the type of alopecia areata seen in relatives.

Several genes have been studied and a large amount of research has focused on human leukocyte antigen. Two studies demonstrated that human leukocyte antigen DQ3 (DQB1*03) was found in more than 80% of patients with alopecia areata, which suggests that it can be a marker for general susceptibility to alopecia areata. The studies also found that human leukocyte antigen DQ7 (DQB1*0301) and human leukocyte antigen DR4 (DRB1*0401) were present significantly more in patients with alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis. [11, 12, 13]

Another gene of interest is the interleukin 1 receptor antagonist gene, which may correlate with disease severity. Finally, the high association of Down syndrome with alopecia areata suggests involvement of a gene located on chromosome 21.

In summary, genetic factors likely play an important role in determining susceptibility and disease severity. Alopecia areata is likely to be the result of polygenic defects rather than a single gene defect. The role of environmental factors in initiating or triggering the condition is yet to be determined.

Cytokines

Interleukin 1 and tumor necrosis factor were shown to be potent inhibitors of hair growth in vitro. Subsequent microscopic examination of these cultured hair follicles showed morphologic changes similar to those seen in alopecia areata.

Innervation and vasculature

Another area of interest concerns the modification of perifollicular nerves. The fact that patients with alopecia areata occasionally report itching or pain on affected areas raises the possibility of alterations in the peripheral nervous system. Circulating levels of the neuropeptide calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) were decreased in 3 patients with alopecia areata compared with control subjects. CGRP has multiple effects on the immune system, including chemotaxis and inhibition of Langerhans cell antigen presentation and inhibition of mitogen-stimulated T-lymphocyte proliferation.

CGRP also increases vasodilatation and endothelial proliferation. Similar findings were reported in another study, in which decreased cutaneous levels of substance P and of CGRP but not of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide were found in scalp biopsy specimens. The study also noted a lower basal blood flow and greater vasodilatation following intradermal CGRP injection in patients with alopecia areata compared with control subjects. More studies are needed to shed light on the significance of these findings.

Viral etiology

Other hypotheses have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of alopecia areata, but more evidence is needed to support them. Alopecia areata was believed to possibly have an infectious origin, but no microbial agent has been isolated consistently in patients. Many efforts have been made to isolate cytomegalovirus, but most studies have been negative. [14]

Etiology

The true cause of alopecia areata remains unknown. The exact role of possible factors needs to be clarified (see Pathophysiology).

No known risk factors exist for alopecia areata, except a positive family history.

The exact role of stressful events remains unclear, but they most likely trigger a condition already present in susceptible individuals, rather than acting as the true primary cause.

Epidemiology

Frequency

Prevalence in the general population is 0.1-0.2%. The lifetime risk of developing alopecia areata is estimated to be 1.7%. Alopecia areata is responsible for 0.7-3% of patients seen by dermatologists. [15, 16]

Race

All races are affected equally by alopecia areata; no increase in prevalence has been found in a particular ethnic group.

Sex

Data concerning the sex ratio for alopecia areata vary slightly in the literature. In one study including 736 patients, a male-to-female ratio of 1:1 was reported. [17] In another study on a smaller number of patients, a slight female preponderance was seen.

Age

Alopecia areata can occur at any age from birth to the late decades of life. Congenital cases have been reported. Peak incidence appears to occur from age 15-29 years. As many as 44% of people with alopecia areata have onset at younger than 20 years. Onset in patients older than 40 years is seen in less than 30% of patients with alopecia areata.[#IntroductionMortalityMorbidity]

Prognosis

Alopecia areata is a benign condition and most patients are asymptomatic; however, it can cause emotional and psychosocial distress in affected individuals. Self-consciousness concerning personal appearance can become important. Openly addressing these issues with patients is important in helping them cope with the condition.

The natural history of alopecia areata is unpredictable. Most patients have only a few focal areas of alopecia, and spontaneous regrowth usually occurs within 1 year. Estimates indicate less than 10% of patients experience extensive alopecia and less than 1% have alopecia universalis. Patients with extensive long-standing conditions are less likely to experience significant long-lasting regrowth.

Adverse prognostic factors include nail abnormalities, atopy, onset at a young age, and severe forms of alopecia areata.

Patient Education

Patient education is a key factor in alopecia areata. Inform patients of the chronic relapsing nature of alopecia areata. Reassure patients that the condition is benign and does not threaten their general health.

Most patients try to find an explanation about why this is happening to them. Reassure these patients that they have done nothing wrong and that it is not their fault.

Inform patients that expectations regarding therapy should be realistic.

Support groups are available in many cities; it is strongly recommended that patients be urged to contact the National Alopecia Areata Foundation at 710 C St, Suite 11, San Rafael, CA 94901 or view the Web site.

Many patients are reluctant to use hairpieces or take part in support groups because, at first, these often are perceived as last-resort options. Take the time to discuss the options with patients because they are of great benefit.

-

Alopecia areata affecting the beard.

-

Alopecia areata affecting the arms.

-

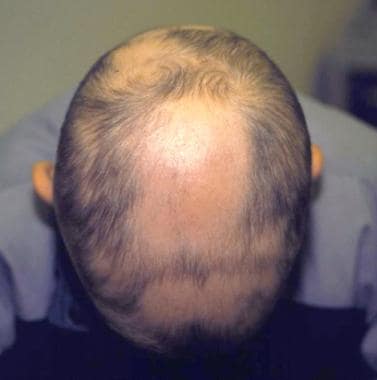

Patchy alopecia areata.

-

Ophiasis pattern of alopecia areata.

-

Sisaipho pattern of alopecia areata.

-

Alopecia totalis.

-

Diffuse alopecia areata.

-

Corticosteroid injection.

-

Treatment algorithm for alopecia areata.