Practice Essentials

Psoriatic arthritis is most commonly a seronegative oligoarthritis found in patients with psoriasis, with less common, but characteristic, differentiating features of distal joint involvement and arthritis mutilans. [1] One in five patients with psoriasis has psoriatic arthritis (see the image below). [2]

Swelling and deformity of the metacarpophalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints in a patient with psoriatic arthritis.

Swelling and deformity of the metacarpophalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints in a patient with psoriatic arthritis.

Go to Psoriatic Arthritis Decision Point for expert commentary on psoriatic arthritis diagnosis and treatment decisions and related guidelines.

Signs and symptoms

Onset of psoriasis and arthritis are as follows:

-

Psoriasis appears to precede the onset of psoriatic arthritis in 60-80% of patients (occasionally by as many as 20 years, but usually by less than 10 years)

-

In as many as 15-20% of patients, arthritis appears before the psoriasis

-

Occasionally, arthritis and psoriasis appear simultaneously

In some cases, patients may experience only stiffness and pain, with few objective findings. In most patients, the musculoskeletal symptoms are insidious in onset, but an acute onset has been reported in one third of all patients.

Findings on physical examination are as follows:

-

Enthesopathy or enthesitis, reflecting inflammation at tendon or ligament insertions into bone, is observed more often at the attachment of the Achilles tendon and the plantar fascia to the calcaneus with the development of insertional spurs

-

Dactylitis with sausage digits is seen in as many as 35% of patients

-

Skin lesions include scaly, erythematous plaques; guttate lesions; lakes of pus; and erythroderma

-

Psoriasis may occur in hidden sites, such as the scalp (where psoriasis frequently is mistaken for dandruff), perineum, intergluteal cleft, and umbilicus

Psoriatic nail changes, which may be a solitary finding in patients with psoriatic arthritis, may include the following:

-

Beau lines

-

Leukonychia

-

Onycholysis

-

Oil spots

-

Subungual hyperkeratosis

-

Splinter hemorrhages

-

Spotted lunulae

-

Transverse ridging

-

Cracking of the free edge of the nail

-

Uniform nail pitting

Extra-articular features are observed less frequently in patients with psoriatic arthritis than in those with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) but may include the following:

-

Synovitis affecting flexor tendon sheaths, with sparing of the extensor tendon sheath

-

Subcutaneous nodules are rare

-

Ocular involvement may occur in 30% of patients, including conjunctivitis in 20% and acute anterior uveitis in 7%; in patients with uveitis, 43% have sacroiliitis

Patterns of arthritic involvement

The patterns of psoriatic arthritis involvement are as follows:

-

Asymmetrical oligoarticular arthritis

-

Symmetrical polyarthritis

-

Distal interphalangeal arthropathy

-

Arthritis mutilans

-

Spondylitis with or without sacroiliitis

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Classification of psoriatic arthritis

The Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) [3] consist of established inflammatory articular disease with at least 3 points from the following features:

-

Current psoriasis (assigned a score of 2)

-

A history of psoriasis (in the absence of current psoriasis; assigned a score of 1)

-

A family history of psoriasis (in the absence of current psoriasis and history of psoriasis; assigned a score of 1)

-

Dactylitis (assigned a score of 1)

-

Juxta-articular new-bone formation (assigned a score of 1)

-

Rheumatoid factor negativity (assigned a score of 1)

-

Nail dystrophy (assigned a score of 1)

Laboratory findings

No specific diagnostic tests are available for psoriatic arthritis. [4] The most characteristic laboratory abnormalities in patients with the condition are as follows:

-

Elevations of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein level

-

Negative rheumatoid factor in 91-95% of patients

-

In 10-20% of patients with generalized skin disease, the serum uric acid concentration may be increased

-

Low levels of circulating immune complexes have been detected in 56% of patients

-

Serum immunoglobulin A levels are increased in two thirds of patients

-

Synovial fluid is inflammatory, with cell counts ranging from 5000-15,000/µL and with more than 50% of cells being polymorphonuclear leukocytes; complement levels are either within reference ranges or increased, and glucose levels are within reference ranges

Radiographic studies

Radiologic features can help distinguish psoriatic arthritis from other causes of polyarthritis. In general, the common subtypes of psoriatic arthritis, such as asymmetrical oligoarthritis and symmetrical polyarthritis, tend to result in only mild erosive disease. Early bony erosions occur at the cartilaginous edge, and cartilage is initially preserved, with maintenance of a normal joint space.

The following radiographic abnormalities are suggestive of psoriatic arthritis:

-

Pencil-in-cup deformity (erosion of the distal end of the phalanx into a sharpened pencil shape, with the proximal surface of the adjoining phalanx worn into a cup shape; see the image below)

-

Joint-space narrowing in the interphalangeal joints, possibly with ankylosis

-

Increased joint space in the interphalangeal joints as a result of destruction

-

Fluffy periostitis

-

Bilateral, asymmetrical, fusiform soft-tissue swelling

-

Unilateral or symmetrical sacroiliitis

-

Large, nonmarginal, unilateral, asymmetrical syndesmophytes (intervertebral bony bridges, seen in the image below) in the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine, often sparing some of the segments

Lateral radiograph of the cervical spine shows syndesmophytes at the C2-3 and C6-7 levels, with zygapophyseal joint fusion. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

Lateral radiograph of the cervical spine shows syndesmophytes at the C2-3 and C6-7 levels, with zygapophyseal joint fusion. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

Magnetic resonance imaging studies:

-

Particularly sensitive for detecting sacroiliitic synovitis, enthesitis, and erosions; can also be used with gadolinium to increase sensitivity

-

May show inflammation in the small joints of the hands, involving the collateral ligaments and soft tissues around the joint capsule, a finding not seen in RA

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Medical treatment regimens include the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). DMARDs include the following [5] :

-

Methotrexate

-

Sulfasalazine

-

Cyclosporine

-

Leflunomide

-

Biologic agents (eg, TNF, PDE4, JAK, or interleukin inhibitors; CD80 binders)

In patients with severe skin inflammation, medications such as methotrexate, retinoic-acid derivatives, and psoralen plus ultraviolet (UV) light should be considered. These agents have been shown to work on skin and joint manifestations. Intra-articular injection of entheses or single inflamed joints with corticosteroids may be particularly effective in some patients. Use DMARDs in individuals whose arthritis is persistent.

Surgical care

-

Arthroscopic synovectomy has been effective in treating severe, chronic, monoarticular synovitis

-

Joint replacement and forms of reconstructive therapy are occasionally necessary

-

Patients in severe pain or with significant contractures may be referred for possible surgical intervention; however, high rates of recurrence of joint contractures have been noted after surgical release, especially in the hand

-

Hip and knee joint replacements have been successful

-

Arthrodesis and arthroplasty have also been used on joints, such as the proximal interphalangeal joint of the thumb

-

The wrist often spontaneously fuses, and this may relieve the patient's pain without surgical intervention

-

For arthritis mutilans, surgical intervention is usually directed toward salvage of the hand; combinations of arthrodesis, arthroplasty, and bone grafts to lengthen the digits may be used

Physical therapy

The rehabilitation treatment program for patients with psoriatic arthritis should be individualized and should be started early in the disease process. Such a program should consider the use of the following:

-

Rest: Local and systemic

-

Exercise: Passive, active, stretching, strengthening, and endurance

-

Modalities: Heat, cold

-

Orthotics: Upper and lower extremities, spinal

-

Assistive devices for gait and adaptive devices for self-care tasks: Including possible modifications to homes and automobiles

-

Education about the disease, energy conservation techniques, and joint protection

-

Possible vocational readjustments

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic inflammatory arthritis that develops in at least 5% of patients with psoriasis. The association between psoriasis and arthritis was first made in the mid-19th century, but psoriatic arthritis was not clinically distinguished from rheumatoid arthritis (RA) until the 1960s.

Risk factors for the development of psoriasis in patients with psoriasis include nail, inverse, and scalp psoriasis; family history of psoriatic arthris, and severity of skin disease. An analysis of 120,523 patients with psoriasis found that the overall 5-year prevalence of psoriatic arthritis was 9.9% in patients with mild psoriasis, 35% in patients with moderate psoriasis, and 54.9% in patients with severe psoriasis. [6] However, no evidence indicates that the severity of the psoriasis relates to the pattern of joint involvement. In another study, pustular psoriasis was associated with more severe psoriatic arthritis.

Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic disease of the joints and the entheses, including those of the axial skeleton. It has associated features that most commonly involve the skin, but may also affect the nails. Dactylitis, uveitis, and osteitis can be associated features.

An example of flexion deformity in psoriatic arthritis is shown below. (See Presentation and Workup.)

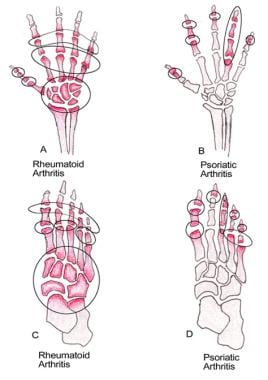

Because of a lack of specific biologic tests, precisely defining psoriatic arthritis remains difficult. The disorder most commonly exists as a seronegative oligoarthritis found in patients with psoriasis. Distal joint involvement and arthritis mutilans are less common, but characteristic, differentiating features. (The first image below compares sites of involvement for psoriatic arthritis with those for RA. The second and third images show distal joint pathology in psoriatic arthritis.)

Comparison between sites of involvements in both hands and feet in psoriatic arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

Comparison between sites of involvements in both hands and feet in psoriatic arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

Because 50% of patients with psoriatic arthritis have evidence of spondyloarthropathy, often human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27 associated, psoriatic arthritis has also been classified among the seronegative spondyloarthropathies. (See Pathophysiology and Etiology.) [7, 8, 9, 10]

Peripheral joint disease occurs in 95% of patients with psoriatic arthritis, while in the other 5%, axial spine involvement occurs exclusively. (See Presentation and Workup.)

Psoriatic arthritis occurring in patients over age 60 years (elderly onset psoriatic arthritis) has a more severe onset and more a destructive outcome than does psoriatic arthritis in younger patients.

The course of psoriatic arthritis is usually characterized by flares and remissions. The patterns of psoriatic arthritis involvement are as follows:

-

Asymmetrical oligoarticular arthritis

-

Symmetrical polyarthritis

-

Distal interphalangeal arthropathy

-

Arthritis mutilans

-

Spondylitis with or without sacroiliitis

Asymmetrical oligoarticular arthritis

This was previously thought to be the most common type of psoriatic arthritis. The digits of the hands and feet are usually affected first, with inflammation of the flexor tendon and synovium occurring simultaneously, leading to the typical "sausage" appearance (dactylitis) of the fingers and toes. A large joint, such as the knee, is also commonly involved. Usually, fewer than 5 joints are affected at any one time. An asymmetrical arthritis pattern is shown below.

Symmetrical polyarthritis

This rheumatoidlike pattern has been recognized as one of the most common types of psoriatic arthritis. The hands, wrists, ankles, and feet may be involved.

It is differentiated from RA by the following:

-

Distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint involvement

-

Relative asymmetry

-

Absence of subcutaneous nodules

-

Negative rheumatoid factor (RF)

-

This condition is also generally milder than RA, with less deformity.

Distal interphalangeal arthropathy

Although DIP joint involvement is considered to be a classic and unique symptom of psoriatic arthritis, it occurs in only 5-10% of patients, primarily men.

Involvement of the nail with significant inflammation of the paronychia and swelling of the digital tuft may be prominent, occasionally making appreciation of the arthropathy more difficult.

Arthritis mutilans

This is a rare form of psoriatic arthritis, being found in only 1-5% of patients (although some reports suggest that arthritis mutilans may occur in as many as 16% of patients and may be as severe as RA).

In arthritis mutilans, resorption of bone (osteolysis), with dissolution of the joint, is observed as the "pencil-in-cup" radiographic finding and leads to redundant, overlying skin with a telescoping motion of the digit. (The effects of arthritis mutilans appear in the images below.)

Arthritis mutilans, a typically psoriatic pattern of arthritis, which is associated with a characteristic "pencil-in-cup" radiographic appearance of digits.

Arthritis mutilans, a typically psoriatic pattern of arthritis, which is associated with a characteristic "pencil-in-cup" radiographic appearance of digits.

Severe psoriatic arthritis showing involvement of the distal interphalangeal joints, distal flexion deformity, and telescoping of the left third, fourth, and fifth digits due to destruction of joint tissue.

Severe psoriatic arthritis showing involvement of the distal interphalangeal joints, distal flexion deformity, and telescoping of the left third, fourth, and fifth digits due to destruction of joint tissue.

This "opera-glass hand" is more common in men than in women and is more frequent in early-onset disease.

Spondylitis with or without sacroiliitis

This occurs in approximately 5% of patients with psoriatic arthritis and has a male predominance.

Clinical evidence of spondylitis and/or sacroiliitis can occur in conjunction with other subgroups of psoriatic arthritis.

Spondylitis may occur without radiologic evidence of sacroiliitis, which frequently tends to be asymmetrical, or sacroiliitis may appear radiologically without the classic symptoms of morning stiffness in the lower back. Thus, the correlation between the symptoms and radiologic signs of sacroiliitis can be poor.

Vertebral involvement differs from that observed in ankylosing spondylitis. Vertebrae are affected asymmetrically, and the atlantoaxial joint may be involved with erosion of the odontoid and subluxation (with attendant neurologic complications). Therapy may limit subluxation-associated disability.

Unusual radiologic features may be present, such as nonmarginal asymmetrical syndesmophytes (characteristic), paravertebral ossification, and, less commonly, vertebral fusion with disk calcification.

SAPHO syndrome

First described by Chamot et al in 1987, synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome is characterized by variable bone changes (hyperostosis, arthritis, aseptic osteomyelitis) of the chest wall, sacroiliac joints, and long bones. Dermatologic manifestations include the following:

-

Palmoplantar pustulosis

-

Hidradenitis suppurativa

-

Pustular psoriasis

-

Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp

-

Sweet syndrome

-

Sneddon-Wilkinson disease

Skin and osseous involvement may occur simultaneously or may be separated by as long as 20 years. [11, 12]

Juvenile psoriatic arthritis

Juvenile psoriatic arthritis accounts for 8-20% of childhood arthritis and is monoarticular at onset.

The median age of onset is 4.5 years in girls and 10 years in boys, and there is a female predominance. The disease is usually mild, although occasionally it may be severe and destructive, with the condition progressing into adulthood.

In 50% of children, the arthritis is monoarticular; DIP joint involvement occurs at a similar rate. Tenosynovitis is present in 30% of children, and nail involvement is present in 71%, with pitting being the most common, but least specific, finding.

In 47% of children, disordered bone growth with resultant shortening may result from involvement of the unfused epiphyseal growth plate in the inflammatory process.

Sacroiliitis occurs in 28% of children and is usually associated with HLA-B27 positivity. Although the presence of HLA-B8 may be a marker of more severe disease, HLA-B17 is usually associated with a mild form of psoriatic arthritis.

Children have a higher frequency of simultaneous onset of psoriasis and arthritis than adults do, with arthritis preceding psoriasis in 52% of children. [13]

Classification of psoriatic arthritis

The simple and highly specific Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR), developed by a large international study group, has a sensitivity and specificity of 98.7% and 91.4%, respectively. [3] The criteria consist of established inflammatory articular disease with at least 3 points from the following features:

-

Current psoriasis (assigned a score of 2)

-

A history of psoriasis (in the absence of current psoriasis; assigned a score of 1)

-

A family history of psoriasis (in the absence of current psoriasis and a history of psoriasis; assigned a score of 1)

-

Dactylitis (assigned a score of 1)

-

Juxta-articular new-bone formation (assigned a score of 1)

-

RF negativity (assigned a score of 1)

-

Nail dystrophy (assigned a score of 1)

Pathophysiology and Etiology

The pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis is still not fully understood. Genetics, environmental factors, and immune-mediated inflammation play complex roles. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis are interrelated disorders, so it is not surprising that they have commonalities in their pathogenesis. However, the fact that some of the new biologics and targeted therapy do not control the joint disease as well as the skin lesions highlights the difference between the two disorders.

Slight differences exist in the vascular patterns of joints in psoriatic arthritis, compared with those of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), suggesting the possibility of different etiologic mechanisms in these diseases. [14]

Genetics

Genetic factors play an important role in susceptibility to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. [15, 16] Approximately 40% of patients with either of those conditions have a family history of them in first-degree relatives. [15, 16]

The recurrence risk ratio for psoriatic arthritis, an estimate of the heritability of the disease, is estimated at 30-55 in first-degree relatives of patients with this condition, while that for psoriasis is 8-10. [17] Diseases with higher heritability have a higher likelihood of having genetic factors underlying disease susceptibility. [18, 19, 20, 21, 22]

The following important genetic susceptibility loci have been found (although the exact mechanism of the association between HLA and psoriatic arthritis is not yet clear) [17, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28] :

-

Early-onset psoriasis: HLA-Cw6, HLA-B57, HLA-DR7, and HLA-B17, with HLA-Cw*0602 variant found to be highly associated

-

Psoriasis: HLA-Cw6 (or psoriasis susceptibility 1 [PSOR1] on chromosome 6) and 6 other psoriasis susceptibility loci (PSOR2, PSOR3, PSOR4, PSOR5, PSOR6, PSOR7), transcription factor RUNX1

-

Psoriatic arthritis: HLA-B7, HLA-B27, HLA-DR4, HLA-38, and HLA-DR7

-

Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: HLA-Cw6, HLA-B13, HLA-B17, HLA-B57, and HLA-B39

-

Predictors of disease progression: HLA-B39; HLA-B27 in the presence of HLA-DR7; HLA-DQ3 in the absence of HLA-DR7

-

Protective: HLA-B22

Comparing psoriasis with psoriatic arthritis, it has been found that in psoriatic arthritis there is a stronger association with HLA-B alleles than with HLA-C alleles, while psoriasis (particularly early onset psoriasis) is associated with HLA-C. [29, 30]

The following associated gene polymorphisms are also thought to be associated with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis [17, 23, 25, 31] :

-

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha promoter [32]

-

Caspase-activating recruitment domain (CARD) 15

Additional loci that demonstrate an association with psoriatic arthritis include microsatellite polymorphisms in the TNF promoter.

In psoriasis, linkages with loci on 17q, 4q, and 6p have been reported in whole-genome scans, with the strongest evidence for linkage on 6p.

Certain immunoglobulin genes may be associated with psoriatic arthritis. Serum levels of immunoglobulin A (IgA) and IgG are higher in psoriatic arthritis patients, whereas IgM levels may be normal or diminished.

Identifying susceptibility genes is likely to aid understanding of disease etiopathogenesis and identify potential therapeutic targets. Although loci identified to date explain only a fraction of the heritability estimates, a model of important pathways in psoriasis pathogenesis is emerging that combines the following [18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 36] :

-

Skin barrier function ( LCE3B, LCE3C)

-

The Th17 pathway ( IL12B, IL23A, IL23R, TRAF3IP2, TYK2)

-

Innate immunity involving receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa beta ligand (RANKL) and interferon signaling ( TNFAIP3, TNIP1, NFKBIA, REL, TYK2, IFIH1, IL23RA)

-

Beta-defensin

-

Th2 ( IL4, IL13)

-

Adaptive immunity involving CD8 T cells ( ERAP1)

A gene-gene interaction between ERAP1 and HLA-C suggesting that ERAP1 variants only influenced psoriasis susceptibility in individuals carrying the HLA-C risk allele further implicates immune dysregulation in psoriasis pathogenesis. [36]

Immunologic factors

Involvement of immunologic mechanisms is suggested by the inflammatory process in psoriatic skin lesions and in the synovial fluid, which can be very similar to the inflammation seen in the synovial fluid in RA. [37] There is an increased level of the proinflammatory cytokines including TNF-alpha, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8 in the synovium and the synovial fluid of psoriatic arthritis patients. Up-regulation of serum IL-10, IL-13, TNF-alpha, and epidermal growth factor also occurs. These changes are similar to those seen in RA patients. [38] Compared with RA patients, however, psoriatic arthritis patients produced less IL-4 and IL-5 in their synovium, had marked vascularity in the synovial lining, and lacked intracellular citrullinated proteins and MHC-Cpg 39 peptides, suggesting that the two diseases have different underlying mechanisms. [39]

The cytokine profile for psoriatic arthritis reflects a complex interplay between T cells and monocyte macrophages. Type 1 helper T-cell cytokines (eg, TNF-alpha, IL-1 beta, IL-10) are more prevalent in psoriatic arthritis than in RA, suggesting that these 2 disorders may have different underlying mechanisms.

T cells play a major role in the development of inflammation in both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. The T cells in the skin are predominantly CD4 positive and CD8 negative, whereas in the synovial fluid they are CD8 positive. Cytokines produced by activated T cells induce the proliferation and activation of fibroblasts in the skin and synovial fluid. Activated T cells may be the cause of arthritis, or it may result from other unknown factors.

Studies suggest that psoriatic arthritis is driven by T helper 17 (Th17) cell activation coupled with TNF-promoted inflammation. This is supported by the disease's clinical response to IL-23/IL-17 inhibitors such ustekinumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab.

TNF-alpha and RANKL upregulation and its effect on osteoclasts are important mechanisms in the pathogenesis of erosive psoriatic arthritis. The mechanism driving peripheral arthritis features such as ankylosis, periostitis, and enthesophyte formation is less understood, but it is thought that prostaglandin E signalling pathways and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) pathways are involved. [40] Finally, mechanically stressed enthesis and local trauma may help drive inflammation in psoriatic arthritis.

Autoantibodies against nuclear antigens, cytokeratins, epidermal keratins, and heat-shock proteins have been reported in persons with psoriatic arthritis, indicating that the disease has a humoral immune component.

Dendritic cells have been found in the synovial fluid of patients with psoriatic arthritis and are reactive in the mixed leukocyte reaction; the inference is that the dendritic cells present an unknown antigen to CD4+ cells within the joints and skin of patients with psoriatic arthritis, leading to T-cell activation. [26]

Psoriatic plaques in skin have increased levels of leukotriene B4. Injections of leukotriene B4 cause intraepidermal microabscesses, suggesting a role for this compound in the development of psoriasis.

Environmental factors

Several environmental factors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. The temporal relationship between certain viral and bacterial infections and the development or exacerbation of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis suggests a possible pathogenetic role for viruses and bacteria, which is theorized to involve the interaction of superantigens with autoantigens.

Pustular psoriasis is a well-described sequela of streptococcal infections. However, the response to streptococcal antigens by cells from patients with psoriatic arthritis is not different from that of cells from patients with RA, making the role of Streptococcus species in psoriatic arthritis doubtful.

Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis have been reported to be associated with HIV infection and to be prevalent in some HIV-endemic areas. Although the prevalence of psoriasis in patients infected with HIV is similar to that in the general population, patients with HIV infection usually have more extensive erythrodermic psoriasis, and patients with psoriasis may present with exacerbation of their skin disease after being infected with HIV.

The Koebner phenomenon (development of new plaques at sites of trauma) is well described with psoriasis, and many patients identified trauma prior to developing joint pain in psoriatic arthritis. Heavy lifting and increased body weight may also confer an increased risk of psoriatic arthritis. There is an inverse association between smoking and psoriatic arthritis, except in HLA-C*06–positive individuals. [41]

Epidemiology

Occurrence in the United States

According to the National Psoriasis Foundation, psoriatic arthritis affects about 1 million people in the United States, or about 30% of all persons with psoriasis. [42] However, prevalence rates vary widely among studies. In one population-based study, less than 10% of patients with psoriasis developed clinically recognized psoriatic arthritis during a 30-year period. A random telephone survey of 27,220 US residents found a 0.25% prevalence rate for psoriatic arthritis in the general population and an 11% prevalence rate in patients with psoriasis. [43] However, the exact frequency of the disorder in patients with psoriasis remains uncertain, with the estimated rate ranging from 5-30%. [44]

Moreover, since the late 20th century, the incidence of psoriatic arthritis appears to have been rising in both men and women. Reasons for the increase are unknown; it may be related to a true change in incidence or to a greater overall awareness of the diagnosis by physicians. [45]

International occurrence

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 28 studies estimated that the global average prevalence of psoriatic arthritis is 133 per 100,000 population (95% confidence interval [CI], 107–164 per 100,000), and the incidence is 83 per 100,000 persons per year (95% CI, 41–167 per 100,000). [46] A systematic review and meta-analysis of 266 studies concluded that worldwide, approximately one in four persons with psoriasis has psoriatic arthritis. [2] However, the prevalence of psoriatic arthritis internationally ranges widely, depending on the population studied. A 2013 German study found the rate of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis to be 30.2%. [47]

In a prospective cohort study from Canada that involved psoriasis patients without arthritis at study entry, 51 of 464 patients developed psoriatic arthritis over the course of 8 years of followup. The annual incidence rate was 2.7 cases of psoriatic arthritis per 100 psoriasis patients. [48] Baseline variables associated with the development of psoriatic arthritis in multivariate analysis included the following:

-

Severe psoriasis (relative risk [RR] 5.4, P = 0.006)

-

Low level of education (college/university vs. high school incomplete, RR 4.5, P = 0.005; high school education vs high school incomplete, RR 3.3, P = 0.049)

-

Use of retinoid medications (RR 3.4, P = 0.02)

There is a high prevalence of previously undiagnosed active psoriatic arthritis among patients with psoriasis who are seen by dermatologists. In a 2009 prospective German study, of 1511 patients with plaque-type psoriasis, 20.6% were found to have psoriatic arthritis, with 85% of the cases having been previously undiagnosed. [7]

The number of diagnosed cases of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has risen dramatically in sub-Saharan Africa in association with the area’s escalating epidemic of HIV infection. Although HIV is not known to affect the incidence of psoriasis, it may significantly exacerbate otherwise limited disease. The evolution of mild psoriasis to erythroderma in the setting of a flare-up of psoriatic arthritis may be a sign of HIV infection.

Race- and age-related demographics

Race predilection in psoriatic arthritis has not been well studied. However, Whites are known to be affected more commonly than are persons of other racial groups. A multiinstitutional study found that although psoriatic arthritis was less frequent in Blacks than in Whites, Blacks had more severe skin involvement. [49]

Psoriatic arthritis characteristically develops in persons aged 35-55 years, but it can occur at almost any age. In the juvenile form, the age of onset is 9-11 years.

Sex-related demographics

The male-to-female ratio for psoriatic arthritis is 1:1, with the exception of some subsets of patients. Females are more commonly affected with symmetrical polyarthritis resembling RA and with the juvenile form. In contrast, the spondylitic form of psoriatic arthritis, which affects the axial spine, has a male-to-female ratio of 3:1.

In a cross-sectional analysis of a large population of patients with psoriatic arthritis, men were found to be more likely to exhibit axial involvement and radiographic joint damage, and women were more likely to experience impaired quality of life and severe limitations in function. [50]

Prognosis

Although psoriatic arthritis was originally thought to be relatively mild, as many as 40% of patients may develop erosive and deforming arthritis. A 1998 study from Switzerland found that about 7% of patients with psoriatic arthritis required musculoskeletal surgery; with the first operation at an average of 13.9 years (range 1-46) after onset of joint disease. [51]

Although a cohort study from the United Kingdom showed no increase in mortality among 453 patients with psoriatic arthritis compared with the general population, [52] a Canadian study reported a significantly greater risk of hypertension, obesity, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular events in patients with psoriatic arthritis than in those with psoriasis without arthritis. Psoriatic arthritis was also associated with infections not treated with antibiotics (presumably viral), neurologic conditions, gastrointestinal disorders, and liver disease. [53]

Labitigan et al reported that the prevalence of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and hypertriglyceridemia was higher in psoriatic arthritis than in RA. Using data from the Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America (CORRONA) registry, the investigators found type 2 diabetes rates in psoriatic arthritis and RA to be 15% and 11%, respectively, and hypertriglyceridemia rates to be 38% and 28%, respectively. [54]

A pooled analysis of two large interventional lipid-lowering trials indicated that intensive statin treatment is effective in inflammatory joint disease, including rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriatic arthritis. Furthermore, statin treatment reduced the risk of cardiovascular disease by 20% in patients with and without inflammatory joint disease. [55]

A Norwegian study of 108 pregnancies in 103 women with psoriatic arthritis found that disease activity decreased in pregnancy and increased within 6 months postpartum. Women who used tumor necrosis factor inhibitors during in pregnancy had significantly lower postpartum disease activity than women who did not use those drugs. [56]

A study from The Netherlands of 708 patients with newly diagnosed psoriatic arthritis concluded that early diagnosis and treatment may improve outcome. Study patients with a diagnostic delay of less than 1 year were more likely to achieve Disease Activity index for PSoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA) remission and Minimal Disease Activity (MDA). Patients with a delay of less than 12 weeks had better outcomes in the first year than those with a delay of 12 weeks to 1 year, but that effect was not sustained over time. [57]

Patient Education

Education is an important component of the psoriatic arthritis treatment plan, because patients must be able to manage their symptoms and be comfortable with self-treatment strategies. Physical therapists can provide education and an exercise program developed individually for each patient. The wrong kind of exercise or overexertion can be harmful to patients with psoriatic arthritis.

Instructing patients with psoriatic arthritis in methods of joint protection is a necessary part of therapy. Patients need to pace themselves and take adequate rest breaks from activity. Other examples of joint protection include the following:

-

Wearing splints on the affected joints

-

Using proper body mechanics and lifting techniques

-

Incorporating assistive devices or adaptive equipment into activities of daily living

For patient education information, see the Psoriatic Arthritis Resource Center and the National Psoriasis Foundation's psoriatic arthritis webpage.

-

Severe fixed flexion deformity of the interphalangeal joint.

-

Comparison between sites of involvements in both hands and feet in psoriatic arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

-

Psoriatic arthritis involving the distal phalangeal joint.

-

Swelling and deformity of the metacarpophalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints in a patient with psoriatic arthritis.

-

Psoriatic arthritis involving the distal phalangeal joint.

-

Psoriatic arthritis involving the distal phalangeal joint.

-

Asymmetrical arthritis pattern of psoriatic arthritis (fixed flexion deformity).

-

Arthritis mutilans, a typically psoriatic pattern of arthritis, which is associated with a characteristic "pencil-in-cup" radiographic appearance of digits.

-

Psoriatic arthritis involving the distal phalangeal joint.

-

Arthritis mutilans (ie, "pencil-in-cup" deformities).

-

Severe psoriatic arthritis showing involvement of the distal interphalangeal joints, distal flexion deformity, and telescoping of the left third, fourth, and fifth digits due to destruction of joint tissue.

-

Psoriatic arthritis showing nail changes, distal interphalangeal joint swelling, and sausage digits.

-

Left, typical appearance of psoriasis, with silvery scaling on a sharply marginated and reddened area of skin overlying the shin. Right, thimblelike pitting of the nail plate in a 56-year-old woman who had suffered from psoriasis for the previous 23 years. Nail pitting, transverse depressions, and subungual hyperkeratosis often occur in association with psoriatic disease of the distal interphalangeal joint. Courtesy of Ali Nawaz Khan, MBBS.

-

Lateral radiograph of the cervical spine shows syndesmophytes at the C2-3 and C6-7 levels, with zygapophyseal joint fusion. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

-

A 37-year-old man presents with a 1-year history of an erythematous and intensely pruritic rash at the bilateral soles of feet. He has mild dryness and fissuring at his hands, but no overlying scale, intense erythema, or itching like that at his feet. Diagnosis: Psoriatic arthritis (PsA), with palmoplantar pustulosis variant of psoriasis. Courtesy of Jason Kolfenbach, MD, and Kevin Deane, MD, Division of Rheumatology, University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine.

-

Patient with psoriatic arthritis involving the joints and skin displays features of arthritis mutilans with distal interphalangeal joint destruction causing a deformity and compromise to function.