Practice Essentials

Exercise-induced asthma is a condition of respiratory difficulty (bronchoconstriction) that is related to histamine release, [1, 2, 3] is triggered by aerobic exercise, and lasts several minutes. Causes include medical conditions, environmental factors, and medications. [4]

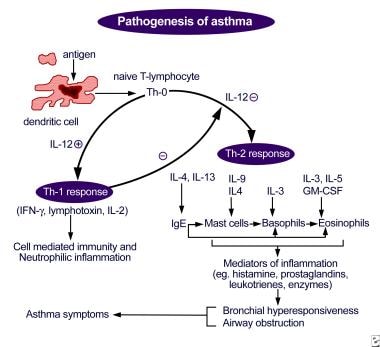

The image below illustrates the pathogenesis of asthma.

Pathogenesis of asthma. Antigen presentation by the dendritic cell with the lymphocyte and cytokine response leading to airway inflammation and asthma symptoms.

Pathogenesis of asthma. Antigen presentation by the dendritic cell with the lymphocyte and cytokine response leading to airway inflammation and asthma symptoms.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of exercise-induced asthma during or following exercise include the following [1, 3] :

-

Chest tightness or pain

-

Cough, shortness of breath, wheezing

-

Underperformance or poor performance on the field of play

-

Fatigue, prolonged recovery time

-

Gastrointestinal discomfort

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

The patient's physical examination is often unremarkable in the clinical setting but may have a higher yield on the field or after an exercise challenge. [5]

Examination should include the following areas:

-

Skin: Note any signs of atopic disease

-

Head, ears, eyes, nose, and throat: Note any evidence of acute infection, chronic infection, or allergic/atopic disease

-

Pharynx: Note any mucus, cobblestoning, and/or erythema

-

Nose: Note presence of enlarged turbinates, erythema, and/or congestion

-

Sinuses: Note presence of tenderness

-

Lungs: Note presence of rales, rhonchi, wheezes, and/or prolonged expiratory phase

-

Heart: Note presence of murmurs and/or an irregular rhythm

Laboratory tests

Exercise-induced asthma is generally a clinical diagnosis. Laboratory evaluation is usually reserved for equivocal cases, for treatment failures, and to narrow the differential diagnosis.

Laboratory studies used to assess for allergy and infection include the following:

-

Complete blood count: To determine likelihood of infection and to evaluate eosinophil counts (for allergy)

-

Immunoglobulin E levels, with/without nasal swab for eosinophils: To determine likelihood of allergic disease

-

Skin allergen testing/radioallergosorbent test: To help identify specific allergens

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein levels: To evaluate for inflammatory and infectious conditions

-

Sputum analysis and culture: To help identify presence of infection and treatment options for strains of resistant organisms

-

Thyroid function tests: To evaluate for thyroid dysfunction if anxiety is suspected of mimicking asthma symptoms

Challenge testing to formalize the diagnosis of exercise-induced asthma includes the following:

-

Treadmill exercise challenges with preexercise and postexercise pulmonary function levels

-

Informal exercise challenge: Substitutes for treadmill exercise challenge; heart rate not monitored, and level of work not reliable

-

Pulmonary function testing: To evaluate baseline pulmonary function or allergic asthma; to categorize pulmonary function as obstructive or restrictive disease

-

Bronchoprovocation testing: Positive results indicative of general asthma rather than specific for exercise-induced asthma

Imaging studies

-

Imaging studies are often not indicated in the evaluation of routine exercise-induced asthma. However, the following radiologic studies may be useful for assessing other possibilities in the differential diagnosis:

-

Chest radiography: To evaluate for signs of chronic lung disease (eg, hyperexpansion, scarring, fibrosis, hilar adenopathy), for congestive heart failure and/or valvular heart disease (eg, chamber enlargement, pulmonary edema, vascular or valvular calcification), and for a foreign body

-

Lateral neck radiography/soft-tissue penetration: To evaluate the upper airway for a foreign body or obstruction

-

Echocardiography: To evaluate for cardiac valvular abnormality or global contractile function, as well as dysrhythmia, cardiomegaly, or other heart disease that may manifest during exercise

Procedures

Laryngoscopy can be performed to evaluate for foreign body or other obstruction in the upper airway. Postexercise laryngoscopy can be used to evaluate for vocal cord dysfunction, a condition often mistaken for exercise-induced asthma.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Treatment of the athlete who is experiencing an acute attack of exercise-induced asthma is the same as in any asthma attack situation and includes immediately removing the patient from competition or play.

The optimal treatment for exercise-induced asthma is to prevent symptomatic onset. After controlling the patient's underlying and contributing factors (eg, respiratory infection, allergy, allergic asthma), a combination of drugs can be used to prevent this condition. [1]

Pharmacotherapy

The basis of treatment for exercise-induced asthma is with preexercise short-acting beta2-agonist administration. [1] There is less of a role for traditional asthma medications (eg, corticosteroids, theophylline) in managing pure exercise-induced asthma.

The following medications are used in the treatment of exercise-induced asthma:

-

Short-acting beta2-adrenergic agonists (eg, albuterol, pirbuterol, levalbuterol)

-

Long-acting beta2-adrenergic agonists (eg, salmeterol, formoterol)

-

Mast cell stabilizers (eg, cromolyn sodium)

-

Inhaled corticosteroids (eg, flunisolide, beclomethasone dipropionate, ciclesonide, fluticasone, budesonide)

-

Xanthine derivatives (eg, theophylline)

-

Leukotriene receptor antagonists (eg, zafirlukast, montelukast)

-

5-Lipoxygenase inhibitors (eg, zileuton)

-

Adrenergic agents (eg, epinephrine)

Other approaches

Nonpharmacologic measures in the treatment of exercise-induced asthma include the following:

-

Sports selection

-

Altering breathing techniques (eg, predominant mouth breathing to nasal breathing)

-

Coordination and timing of warm-up techniques, medication, and competition

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Exercise-induced asthma (EIA) is a condition of respiratory difficulty that is related to histamine release, [1, 2, 3] triggered by aerobic exercise, and lasts several minutes (see Pathophysiology). Causes include medical conditions, environmental factors, and medications (see Etiology). [4]

Symptoms of EIA may resemble those of allergic asthma, or they may be much more vague and go unrecognized, resulting in probable underreporting of the disease (see Clinical Presentation). The optimal treatment for EIA is to prevent the onset of symptoms, and the basis of treatment is with preexercise short-acting β2 -agonist administration. [1] Long-acting β2 -agonists and mast cell stabilizers, as well as antileukotriene drugs have also been shown to be effective (see Treatment and Management). [8, 9]

With proper interventions, the prognosis is excellent for athletes with asthma. Most symptoms can be prevented, and performance should not be limited by EIA with proper treatment (see Prognosis).

Exercise-induced urticaria, or exercise-induced anaphylaxis, is often presumed to be related to EIA, even though this condition is extremely rare and unrelated (see Diagnostic Considerations).

Go to Asthma, Pediatric Asthma, Exercise-Induced Anaphylaxis, Angioedema, and Urticaria for more information on these topics.

Anatomy

The problem with the functional anatomy in exercise-induced asthma (EIA) occurs distal to the glottis, in the lower airway. Bronchoconstriction is involved that is distinguishable from laryngospasm, which can occur in other exercise-related conditions. One such example is the condition known as vocal cord dysfunction in which there is paradoxical narrowing of the vocal cords during inspiration, resulting in stridor that is often misconstrued as audible wheezing. [10, 11] Normally, the vocal cords open with inspiration. (Go to Vocal Cord Dysfunction for more information on this topic.)

Pathophysiology

EIA usually affects individuals who participate in sports that include an aerobic component. The condition can be seen in any sport, but EIA is much less common in predominantly anaerobic activities. This is likely due to the role of consistent and repetitive air movement through the airways (seen in aerobic sports), which affect airway humidity and temperature. EIA triggers an unknown biochemical and neurochemical pathway, resulting in the bronchospasm, which manifests as the symptoms of the disease.

Although the exact mechanism of EIA is unknown, there are 2 predominant theories as to how the symptom complex is triggered. One is the airway humidity theory, which suggests that air movement through the airway results in relative drying of the airway. This, in turn, is believed to trigger a cascade of events that results in airway edema secondary to hyperemia and increased perfusion in an attempt to combat the drying. The result is bronchospasm.

The other theory is based on airway cooling and assumes that the air movement in the bronchial tree results in a decreased temperature of the bronchi, which may also trigger a hyperemic response in an effort to heat the airway. Again, the result is a spasm in the bronchi.

Many authors believe there may be a combination of the above 2 theories that takes place, but the biochemical or physical pathways that mediate these responses are unclear. Evidence may even exist to support the idea that the resulting cascades are not the inflammatory pathways to which we attribute allergic asthma.

Likewise, certain sports and their environments predispose individuals with asthma to experience EIA. Sports played in cold and dry environments usually result in more symptom manifestation for athletes with this condition. On the other hand, when the environment is warm and humid, the incidence and severity of EIA decrease.

Also see the figure below.

Etiology

The causes of EIA can be divided into the categories of medical, environmental, and drug related. Eliminating some causes can diminish—but may not eliminate—the athlete's symptoms. EIA may also exist without the presence of any of these causes.

Medical conditions

Poorly controlled asthma results in increased patient symptoms with exercise. Maximizing control of the patient's baseline asthma, when present, is critical in the treatment of EIA. [1] In addition, poorly controlled allergic rhinitis also results in increased patient symptoms with exercise, and secretions resulting from hay fever can aggravate both allergic asthma and EIA.

Viral, bacterial, and other forms of upper respiratory tract infections also aggravate the symptoms of EIA. Controlling the secretions of these illnesses, as with allergic rhinitis, can make the EIA symptoms much more tolerable.

Environmental factors

Excess of pollens or other allergens in the air can exacerbate the allergic and exercise-induced forms of asthma. Pollutants in the air are irritants to the airways and can lower the threshold for symptomatic bronchospasm.

The chemicals used in certain sports for environmental maintenance can predispose individuals to wheezing and worsen EIA symptoms. These chemicals include the following:

-

Chlorination in pools

-

Insecticides and pesticides used to maintain playing fields

-

Fertilizers and herbicides used to maintain playing fields

-

Paints and other decorative substances to enhance the appearance of playing fields

Asthmogenic agents

Certain medication classifications and specific drugs can provoke or exacerbate bronchial reactivity in EIA, such as the following:

-

β-blockers

-

Aspirin

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

-

Diuretics

-

Zanamivir

Epidemiology

EIA affects 12-15% of the population. Ninety percent of asthmatic individuals and 35-45% of people with allergic rhinitis experience EIA, but even when those with rhinitis and allergic asthma are excluded, a 3-10% incidence of EIA is seen in the general population. [3, 12]

EIA seems to be more prevalent in some winter or cold-weather sports. [13] Some studies have demonstrated rates as high as 35% or even 50% in competitive-caliber figure skaters, ice hockey players, and cross-country skiers. [14, 6, 15] EIA is also more common among swimmers. [16]

An observational cohort study of 149 pediatric asthma patients found that exercise-induced bronchoconstriction was present in 52.5% of these children. [17]

Prognosis

The prognosis is excellent for athletes with asthma. With proper interventions, most symptoms can be prevented, and performance should not be limited by EIA if this condition is treated properly. Newly diagnosed young athletes need to be educated that this condition should not be perceived as an insurmountable disability. Using examples of the numerous elite athletes (eg, Jackie Joyner-Kersee [track and field Olympian]; Amy Van Dyken [Olympic swimmer]; Jerome Bettis [former running back for the Pittsburgh Steelers]) with this condition can help young impressionable athletes continue in their endeavors without fear of failure or medical distress.

Patient Education

Patient education is a critical part of the treatment of EIA. Once the diagnosis is made, athletes should be encouraged to continue in their activities with the reassurance that proper treatment can allow for an unhampered performance for most individuals.

In addition to reassurance, it is also important to teach individuals to recognize the signs of an impending attack. Once recognized, individuals should be taught to remove themselves from the aggravating activity and initiate treatment as necessary. This includes education about the proper choice of agents to abort an acute attack (ie, albuterol), but not cromolyn, salmeterol, or an inhaled steroid.

Teaching the proper mechanics of inhalant medication administration is also important, along with, if needed, teaching and demonstrating the proper use of a spacer device to the patient; without the proper mechanics in using such devices, the medication does not reach the area of pathology and does not benefit the athlete.

Education of the coaching staff is also crucial, because coaches need to know that shortness of breath in athletes does not always indicate poor conditioning and that the consequences of ignoring an asthma attack can be serious.

-

Pathogenesis of asthma. Antigen presentation by the dendritic cell with the lymphocyte and cytokine response leading to airway inflammation and asthma symptoms.