Practice Essentials

Congenital anomalies of the kidneys include a group of so-called fusion anomalies, in which both kidneys are fused together in early embryonic life. Fusion anomalies of the kidneys can generally be placed into 2 categories: (1) horseshoe kidney and its variants and (2) crossed fused ectopia. Horseshoe kidney is probably the most common fusion anomaly. The term horseshoe kidney refers to the appearance of the fused kidney, which results from fusion at one pole (see some examples in the images below). In more than 90% of cases, fusion occurs along the lower pole. Technically, the term horseshoe kidney is reserved for cases in which most of each kidney lies on one side of the spine. It includes symmetrical horseshoe kidney (midline fusion) or asymmetrical horseshoe kidney (L-shaped kidney). In the latter, the fused part, or isthmus, lies slightly lateral to the midline (lateral fusion). Horseshoe kidney is generally differentiated from crossed fused ectopia, in which both fused kidneys lie on one side of the spine, and the ureter of the crossed kidney crosses the midline to enter the bladder. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

Plain radiograph of the abdomen shows calcific opacities in the region of left lower renal pole. Note the reversed axis of the kidneys, which suggests horseshoe kidney.

Plain radiograph of the abdomen shows calcific opacities in the region of left lower renal pole. Note the reversed axis of the kidneys, which suggests horseshoe kidney.

Intravenous urogram (IVU) demonstrates horseshoe kidney. Note the malrotated collecting systems on both sides. The lower pole calyx of the right kidney lies medial to the ureter.

Intravenous urogram (IVU) demonstrates horseshoe kidney. Note the malrotated collecting systems on both sides. The lower pole calyx of the right kidney lies medial to the ureter.

Axial computed tomography (CT) scan obtained through the abdomen after the intravenous administration of contrast material. Fused kidneys are revealed, with a parenchymal isthmus at the lower poles. Note the malrotated collecting system of the left kidney, facing anterolaterally.

Axial computed tomography (CT) scan obtained through the abdomen after the intravenous administration of contrast material. Fused kidneys are revealed, with a parenchymal isthmus at the lower poles. Note the malrotated collecting system of the left kidney, facing anterolaterally.

About a third of all patients with horseshoe kidneys remain completely asymptomatic and are often found incidentally during imaging. However, horseshoe kidneys predispose individuals to a number of urologic complications due to the associated ureteric obstruction and impaired urinary drainage. Ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJ) is the most common abnormality associated with horseshoe kidneys; affected individuals are also predisposed to hydronephrosis, infection, and vesicoureteral reflux. [6] Kidney stones have a reported incidence of 36% in adult patients with horseshoe kidney. [7] Because of their ectopic position, horseshoe kidneys are also particularly susceptible to blunt abdominal trauma and can be compressed or fractured against the lumbar vertebrae. [6, 5]

Preferred examination

Intravenous urography (IVU), computed tomography (CT) scanning, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and scintigraphy depict horseshoe kidney with a high degree of accuracy. [8, 9, 10, 11, 1, 12] For the purpose of diagnosis, IVU is usually the first-line investigation, followed by CT scanning or scintigraphy in cases with doubtful findings. Ultrasonography is also helpful, but it may have some technical limitations. Most of the time, IVU cannot be used to differentiate between a fibrous isthmus and a parenchymal isthmus. Also, in many cases, the diagnosis of a horseshoe kidney is difficult to make on the basis of only IVU findings. In these instances, CT scanning or scintigraphy may be helpful. On IVUs, a malrotated or an ectopic kidney may sometimes be confused with horseshoe kidney.

Although MRI accurately reveals the anatomy associated with horseshoe kidney, it is not generally used for diagnosis because of its high cost. MR angiography provides additional information about the vascular anatomy. A voiding cystourethrogram is usually required to evaluate associated vesicoureteric reflux. A diuretic renal scintigram is helpful in differentiating obstructed and nonobstructed dilated collecting systems. Angiography is usually reserved for presurgical planning to fully evaluate the arterial supply pattern.

CT angiography scanning with 3-dimensional reconstruction also may reveal the vascular anatomy and collecting system for presurgical planning.

Ultrasonography sometimes has technical limitations, especially in patients with a large body habitus, in whom visualization of the isthmus may be difficult. Also, horseshoe kidney may be missed on routine abdominal scans unless particular attention is paid to ruling out this condition.

On images, differentiation between horseshoe kidney and cross fused ectopia may not always be possible. [13]

Gibbous deformity of the spine may alter the renal axis, which may then resemble horseshoe kidney.

Radiography

IVU usually reveals the classic findings associated with horseshoe kidney. Findings on the initial tomogram may be deceptive because of the exclusion of the anteriorly lying isthmus. Renal axis abnormalities are confirmed, as seen on the plain radiographs (see the images below). In midline fusion, the kidneys are symmetrical, with the lower pole calyces lying closer to or actually overlying the spine. The lower calyces are usually medially rotated, and they may actually lie medial to the ureters. Some degree of malrotation of the kidneys is usually present. A renal pelvis is often extrarenal and large.

Plain radiograph of the abdomen shows calcific opacities in the region of left lower renal pole. Note the reversed axis of the kidneys, which suggests horseshoe kidney.

Plain radiograph of the abdomen shows calcific opacities in the region of left lower renal pole. Note the reversed axis of the kidneys, which suggests horseshoe kidney.

Intravenous urogram (IVU) shows an altered renal axis with medially directed lower renal poles, which suggests horseshoe kidney. Also note the dilated collecting system of the left kidney, resulting from a ureteropelvic junction obstruction; this is a frequently associated finding.

Intravenous urogram (IVU) shows an altered renal axis with medially directed lower renal poles, which suggests horseshoe kidney. Also note the dilated collecting system of the left kidney, resulting from a ureteropelvic junction obstruction; this is a frequently associated finding.

Intravenous urogram (IVU) demonstrates horseshoe kidney. Note the malrotated collecting systems on both sides. The lower pole calyx of the right kidney lies medial to the ureter.

Intravenous urogram (IVU) demonstrates horseshoe kidney. Note the malrotated collecting systems on both sides. The lower pole calyx of the right kidney lies medial to the ureter.

Intravenous urogram (IVU) of a male patient displays findings consistent with the presence of horseshoe kidney.

Intravenous urogram (IVU) of a male patient displays findings consistent with the presence of horseshoe kidney.

The degree of malrotation has been associated with the degree of fusion. If the isthmus is narrow, the kidneys are usually less malrotated, with the pelvis lying anteromedially in its near-normal position. In cases of a wide isthmus, the renal pelves lie anteriorly or laterally. Associated UPJ obstruction may be present because of the higher ureteric insertion point, which leads to delayed pelvic emptying. Ureters may have the so-called flower-vase appearance, in which the upper ureters diverge laterally over the isthmus and then converge inferiorly.

The L-shaped kidney's lateral fusion anomaly can also be readily appreciated on IVUs. In this anomaly, one kidney has a relatively vertical position, while the other kidney is relatively horizontal.

Degree of confidence

Plain radiographs may show low-lying renal outlines with an altered renal axis. Usually, the kidneys follow the axis of the psoas muscles, with the lower poles lying at a more lateral position than the upper poles. In horseshoe kidney, this axis is reversed, with the lower poles lying closer to the spine. With plain radiographs alone, however, the degree of confidence in this finding is usually low.

The degree of confidence associated with IVU for the diagnosis of horseshoe kidney is high in most cases. Sometimes, ascertaining the diagnosis on the basis of IVU alone is difficult, and further workup—using CT scanning, MRI, or scintigraphy—may be necessary. IVU is also a good modality for discovering associated findings, such as the presence of stones, scarring, and duplex collecting systems.

Malrotated kidneys can sometimes be mistaken for horseshoe kidneys. IVU does not aid in the differentiation of a parenchymal isthmus from a fibrous isthmus.

Computed Tomography

Contrast-enhanced CT scanning has a high degree of accuracy in defining the structural abnormalities of horseshoe kidney, including the degree and site of fusion, the degree of malrotation, associated renal parenchymal changes (eg, scarring, cystic disease), and collecting system abnormalities (eg, duplex system, hydronephrosis). It can also be used to differentiate a parenchymal isthmus from a fibrous isthmus and to show the relation of the isthmus to surrounding structures. [12]

(See the images below.)

Axial computed tomography (CT) scan obtained through the abdomen after the intravenous administration of contrast material. Fused kidneys are revealed, with a parenchymal isthmus at the lower poles. Note the malrotated collecting system of the left kidney, facing anterolaterally.

Axial computed tomography (CT) scan obtained through the abdomen after the intravenous administration of contrast material. Fused kidneys are revealed, with a parenchymal isthmus at the lower poles. Note the malrotated collecting system of the left kidney, facing anterolaterally.

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen obtained after the intravenous administration of contrast material. The isthmus of a horseshoe kidney, consisting of parenchymal tissue, is clearly demonstrated. Note the cortical continuity of the fused kidneys.

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen obtained after the intravenous administration of contrast material. The isthmus of a horseshoe kidney, consisting of parenchymal tissue, is clearly demonstrated. Note the cortical continuity of the fused kidneys.

Although routine CT scanning may show the variant arterial supply, this is better defined with CT angiography scanning with 3-dimensional reconstruction and volume rendering. In cases of neoplasm associated with horseshoe kidney, the use of 3-dimensional, multisection helical CT scanning has also been advocated, because it further clarifies the structural details. [10]

The degree of confidence associated with the use of CT scanning for diagnosing horseshoe kidney is high. However, associated stone disease may be missed with contrast-enhanced CT scanning alone, and nonenhanced CT scanning, ultrasonography, or plain radiography may be required.

Glodny et al examined the radiologic findings of horseshoe kidneys and crossed fused ectopias in 209 patients to assess the frequency and clinical significance of associated anomalies and diseases. CT scanning was the most reliable imaging modality for both horseshoe kidneys and crossed fusion ectopias, but individual cases with complex anatomic configurations required special examination strategies. Crossed fused ectopias differed anatomically from horseshoe kidneys in having a lower position, greater axial rotation, smaller pelvic width, more caudal origin, and fewer vessels. Children had higher rates of malformations than adults. [14]

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI has an advantage in depicting structural details because of its ability to permit multiplanar imaging, but it is more costly than other examinations. However, an added advantage may be obtained by using MR angiography to delineate the vascular anatomy. MRI is probably the best modality to use in evaluating the extent of renal tumors associated with horseshoe kidney. The degree of confidence connected with the use of MRI for the diagnosis of horseshoe kidney, as well as for the purpose of defining associated structural findings, is high. However, associated small stones may be missed on MRIs.

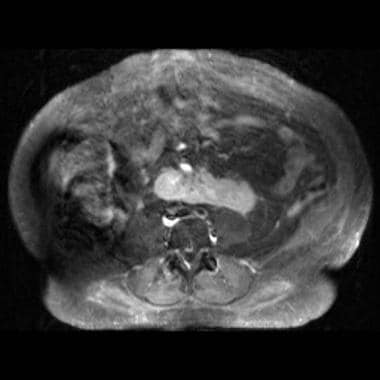

(See the image below.)

Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance image shows the isthmus of a horseshoe kidney; it consists of parenchymal tissue and lies anterior to the spine.

Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance image shows the isthmus of a horseshoe kidney; it consists of parenchymal tissue and lies anterior to the spine.

Ultrasonography

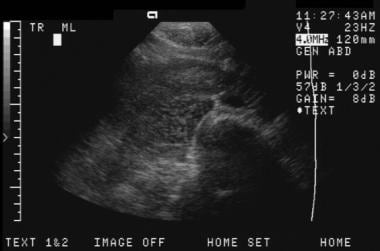

Ultrasonography can be useful for diagnosing horseshoe kidney. To establish the diagnosis, the most important ultrasonographic findings are the presence of the isthmus and its continuity with the lower poles. Other features, such as malrotation and an altered renal axis, may be difficult to assess with ultrasonography. In cases in which the isthmus is composed of only a thin, fibrous band, this midline soft tissue may not be seen. (See the images below.)

Transverse ultrasonogram of the abdomen showing a soft-tissue hypoechoic mass (isthmus) that is anterior to the spine and aorta and that unites the lower renal poles.

Transverse ultrasonogram of the abdomen showing a soft-tissue hypoechoic mass (isthmus) that is anterior to the spine and aorta and that unites the lower renal poles.

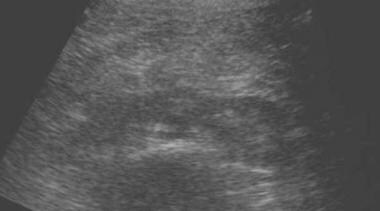

Transverse slightly oblique ultrasonogram of the right kidney, showing the lower pole of the right kidney; the pole crosses over the spine, anterior to the aorta and inferior vena cava.

Transverse slightly oblique ultrasonogram of the right kidney, showing the lower pole of the right kidney; the pole crosses over the spine, anterior to the aorta and inferior vena cava.

Ultrasonogram of a pediatric patient displays a hypoechoic soft-tissue mass anterior to the spine. The finding is consistent with the presence of horseshoe kidney.

Ultrasonogram of a pediatric patient displays a hypoechoic soft-tissue mass anterior to the spine. The finding is consistent with the presence of horseshoe kidney.

Various findings, such as a curved configuration of the lower poles, elongation of the lower poles, and poorly defined lower poles, suggest the presence of horseshoe kidney. Other associated findings, such as stones, hydronephrosis, and cortical scarring, are reliably depicted on sonograms. Ultrasonography has also been useful in the diagnosis of horseshoe kidney in utero. [11]

The degree of confidence depends on the visualization of the isthmus and the proof of its continuity with the lower poles. In many patients, especially those with a large body habitus, overlying bowel gas makes the acquisition of adequate scans difficult for technical reasons. In cases in which the continuity of the poles with the isthmus cannot be clearly demonstrated, the degree of confidence is low.

Occasionally, a midline soft-tissue mass over the spine (eg, a lymphomatous mass) may be mistaken for an isthmus, especially if it extends laterally to the kidneys. If a horseshoe kidney has a thin, fibrous isthmus, ultrasonography may produce a false-negative result.

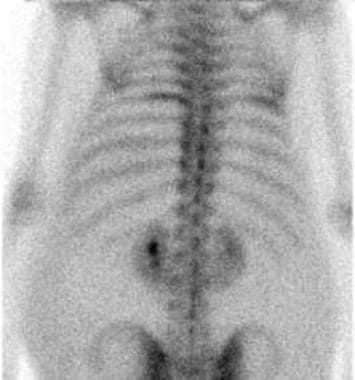

Nuclear Imaging

Scintigraphy best demonstrates the fusion if the isthmus consists of functioning parenchymal tissue, because this imaging modality depends not only on the structure of the tissue but also on the function of the tissue. Technetium-99m (99mTc)–labeled dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) can be used to define the fused segments, as well as the altered axis of both kidneys.

Many reports of horseshoe kidney exist. This condition is incidentally diagnosed on bone scans, 99mTc-labeled red blood cell studies, or other nuclear medicine studies obtained for reasons other than the evaluation of horseshoe kidney. The use of mercaptoacetyltriglycine (MAG-3) with diuresis is helpful in differentiating nonobstructed parts from obstructed parts of the collecting systems.

Horseshoe kidney can be confidently diagnosed with scintigraphy, which reveals the functioning parenchymal isthmus. Occasionally, the hot isthmus of a horseshoe kidney can be mistaken for spinal metastatic disease.

(See the image below.)

Posterior technetium-99m methylene diphosphonate nuclear medicine bone scan shows incidental findings that suggest horseshoe kidney.

Posterior technetium-99m methylene diphosphonate nuclear medicine bone scan shows incidental findings that suggest horseshoe kidney.

Angiography

Angiography is not normally performed to diagnose horseshoe kidney, but it is performed to evaluate the vascular anatomy and its variations in a presurgical setting. Angiograms may show 1, 2, or 3 renal arteries in either of the fused kidneys and can reveal large variations in the blood supply of the isthmus. In cases of associated renal tumors, angiography is used to evaluate tumor vascularity. Angiography is occasionally performed to check renal artery stenosis in hypertensive patients who have horseshoe kidney.

(See the image below.)

-

Plain radiograph of the abdomen shows calcific opacities in the region of left lower renal pole. Note the reversed axis of the kidneys, which suggests horseshoe kidney.

-

Intravenous urogram (IVU) shows an altered renal axis with medially directed lower renal poles, which suggests horseshoe kidney. Also note the dilated collecting system of the left kidney, resulting from a ureteropelvic junction obstruction; this is a frequently associated finding.

-

Intravenous urogram (IVU) demonstrates horseshoe kidney. Note the malrotated collecting systems on both sides. The lower pole calyx of the right kidney lies medial to the ureter.

-

Axial computed tomography (CT) scan obtained through the abdomen after the intravenous administration of contrast material. Fused kidneys are revealed, with a parenchymal isthmus at the lower poles. Note the malrotated collecting system of the left kidney, facing anterolaterally.

-

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen obtained after the intravenous administration of contrast material. The isthmus of a horseshoe kidney, consisting of parenchymal tissue, is clearly demonstrated. Note the cortical continuity of the fused kidneys.

-

Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance image shows the isthmus of a horseshoe kidney; it consists of parenchymal tissue and lies anterior to the spine.

-

Transverse ultrasonogram of the abdomen showing a soft-tissue hypoechoic mass (isthmus) that is anterior to the spine and aorta and that unites the lower renal poles.

-

Transverse slightly oblique ultrasonogram of the right kidney, showing the lower pole of the right kidney; the pole crosses over the spine, anterior to the aorta and inferior vena cava.

-

Posterior technetium-99m methylene diphosphonate nuclear medicine bone scan shows incidental findings that suggest horseshoe kidney.

-

Angiogram shows incidental findings of a horseshoe kidney. The lower poles are connected by a fibrous isthmus.

-

Transverse sonogram of the abdomen demonstrates a soft-tissue isthmus anterior to the spine.

-

Intravenous urogram (IVU) of a male patient displays findings consistent with the presence of horseshoe kidney.

-

Ultrasonogram of a pediatric patient displays a hypoechoic soft-tissue mass anterior to the spine. The finding is consistent with the presence of horseshoe kidney.