Practice Essentials

Epiglottitis is a rapidly developing inflammation of the epiglottis and adjacent tissues, usually due to a bacterial infection, that can cause life-threatening airway obstruction. Historically, epiglottitis was a disease of childhood, and the most common pathogen was Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib). After the introduction of the Hib vaccine in 1985, followed by the recommendation of routine infant vaccination in the United States beginning in 1991, the incidence of epiglottitis dramatically declined in children. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9] Today, there is no predominant pathogen implicated in epiglottitis. Hib epiglottitis is still occasionally seen, accounting for 6 out of 19 cases in a series by Shah and colleagues. [7] It occurs in vaccinated and nonvaccinated patients, because the vaccine is not 100% effective. [10, 11, 12]

Using data from the National Vital Statistics System, Allen et al reported that mortality of acute epiglottitis in the United States decreased from 65 in 1979 (24 adult deaths; 41 pediatric and adolescent deaths) to 15 in 2017 (14 adult deaths; 1 pediatric/adolescent death). [1]

Findings on lateral neck radiographs are frequently diagnostic. A single, lateral, upright view of the neck in extension, preferably with a closed mouth, is usually adequate. The radiograph should be obtained with portable equipment in the emergency department (ED), because acute airway obstruction may occur at any time. [13] In severe cases, radiographs should not be acquired until the airway is secured. In epiglottitis, the epiglottis appears swollen and enlarged (the thumb or thumbprint sign; see the image below). [14, 2, 4, 13, 15]

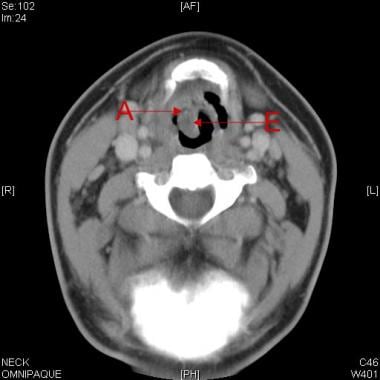

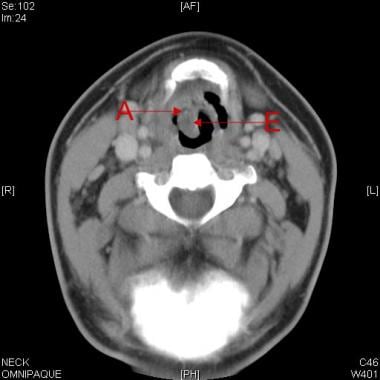

Image in a 66-year-old patient with acute epiglottitis. The epiglottis (E) is swollen and its appearance is thumblike rather than petal-like. The aryepiglottic folds (A) also are swollen and are more radiopaque than normal.

Image in a 66-year-old patient with acute epiglottitis. The epiglottis (E) is swollen and its appearance is thumblike rather than petal-like. The aryepiglottic folds (A) also are swollen and are more radiopaque than normal.

Direct visualization of the epiglottis using nasopharyngoscopy/laryngoscopy is the preferred method of diagnosis, and radiographs are not required when the diagnosis can be made by history and physical examination alone or with direct visualization. [16] Direct nasopharyngolaryngoscopy should be performed only when measures to immediately secure the airway are available in the ED or operating room.

The use of computed tomography (CT) scanning is risky in the diagnosis of epiglottitis, but it may help in the evaluation of complications, such as abscess formation. CT scanning should be approached with caution because the supine position increases the risk of acute respiratory distress. As with CT scanning, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not recommended for initial diagnosis but may be useful for excluding potential mimickers of epiglottitis.

Widespread use of ultrasonography in the ED has led to its use in the diagnosis of acute epiglottitis. [17, 18, 19, 20]

An inability to hyperextend the patient's neck because of irritability may interfere with diagnostic accuracy. An image obtained with the patient's mouth open may decrease the probability of seeing true obliteration of the vallecula.

Direct examination of the pharynx or anxiety caused by diagnostic tests may precipitate acute airway obstruction. If crying occurs, rapid inspiration through the swollen epiglottis can cause the airway to close completely. Finally, a suboptimally low kilovolt setting may cause poor depiction of the soft tissues.

(See the images of acute epiglottitis below.)

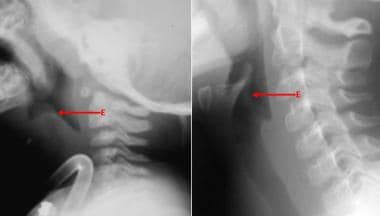

The normal epiglottis in the image on the right is contrasted with the markedly thickened one on the left. Although the epiglottis is swollen, a column of air can still be seen.

The normal epiglottis in the image on the right is contrasted with the markedly thickened one on the left. Although the epiglottis is swollen, a column of air can still be seen.

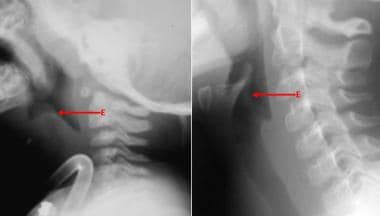

Computed tomography (CT) scan in an adult with acute epiglottitis shows a column of air around the epiglottis (E). The right side is more swollen than the left, and the hypo-attenuating area (A) is suggestive of fluid or the early formation of an abscess.

Computed tomography (CT) scan in an adult with acute epiglottitis shows a column of air around the epiglottis (E). The right side is more swollen than the left, and the hypo-attenuating area (A) is suggestive of fluid or the early formation of an abscess.

In addition to Hib, bacterial culprits include groups A beta-hemolytic streptococci, particularly Streptococcus pyogenes and S pneumoniae, [11] as well as Staphylococcus aureus. Rare causes include H parainfluenzae, influenza B viruses, herpes simplex virus (HSV), and H influenzae (including type A and type F, as well as nontypeable strains). Infrequently, thermal injury from the consumption of hot liquids, corrosive ingestion, and various lymphoproliferative disorders have been implicated as noninfectious causes of epiglottitis.

Epiglottitis in adults differs from that in children. It is typically a less severe because the epiglottis becomes smaller and more rigid in adulthood and susceptibility to obstruction by inflammation is reduced. The predominant presenting complaint in adults is sore throat. [21] Other common symptoms include fever, dysphonia, stridor, dysphagia and dyspnea. Comorbid diabetes mellitus and hypertension were present in nearly a third of patients in one study. [22]

Radiography

Soft-tissue, lateral neck radiography has a sensitivity of 88-100% and a specificity of 87-96% in diagnosing epiglottitis. [23] On plain radiographs, the normal epiglottis is a thin, curved flap of soft-tissue opacity that is separated from the base of the tongue by air in the vallecula. In epiglottitis, the epiglottis appears swollen and enlarged (the thumb or thumbprint sign; see the third image below), typically greater than 8 mm in adults. [14, 2, 4, 13, 15]

An enlarged epiglottis may result from various disorders, including irritation from a foreign body or burn, granulomatous disease (eg, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, Wegener granulomatosis), angioneurotic edema, and tumors, such as epiglottic cysts and neoplasms (eg, lymphomas)

Often, only a pencil-thin airway or no air column is visible in the shadow of the epiglottis. As edema develops, the epiglottis expands, obliterating the vallecula. Loss of the vallecula has been said to be an independently sensitive and specific sign of adult epiglottitis, although further validation is needed. [24]

(See the radiographic images below.)

The normal epiglottis in the image on the right is contrasted with the markedly thickened one on the left. Although the epiglottis is swollen, a column of air can still be seen.

The normal epiglottis in the image on the right is contrasted with the markedly thickened one on the left. Although the epiglottis is swollen, a column of air can still be seen.

Image shows a normal epiglottis in a child; however, the prevertebral space is wide, and retropharyngeal swelling and a retropharyngeal abscess are present. Note the petal-like appearance of the epiglottis and the column of air extending up its midline.

Image shows a normal epiglottis in a child; however, the prevertebral space is wide, and retropharyngeal swelling and a retropharyngeal abscess are present. Note the petal-like appearance of the epiglottis and the column of air extending up its midline.

Image in a 66-year-old patient with acute epiglottitis. The epiglottis (E) is swollen and its appearance is thumblike rather than petal-like. The aryepiglottic folds (A) also are swollen and are more radiopaque than normal.

Image in a 66-year-old patient with acute epiglottitis. The epiglottis (E) is swollen and its appearance is thumblike rather than petal-like. The aryepiglottic folds (A) also are swollen and are more radiopaque than normal.

Thickening of the aryepiglottic folds and thickening of the arytenoids are associated findings in 85% and 70% of cases of epiglottitis, respectively. Aryepiglottic fold thickening greater than 7 mm is a particularly sensitive and specific finding in children and adults. [14]

Prevertebral soft-tissue swelling and hypopharyngeal widening are additional associated findings. In children, ballooning of the hypopharynx, caused by sucking air through an open mouth against an obstruction, is occasionally seen due to laxity of the immature airway. Hypopharyngeal widening and ballooning, however, are nonspecific findings associated with any cause of upper airway obstruction.

The following additional parameters for diagnosing epiglottitis in adults have been proposed: [23, 25]

-

Epiglottic height-to-width ratio >0.6

-

Epiglottic to C4 vertebral body width ratio >0.33

-

Aryepiglottic fold to C3 vertebral body width ratio >0.35

-

Prevertebral soft-tissue to C4 vertebral body width ratio >0.25

-

Hypopharyngeal airway to C4 vertebral body width ratio >1.5

The presence of any of these signs should raise the suspicion that epiglottitis is present, although diagnostic accuracy increases when multiple findings exist.

Computed Tomography

The use of computed tomography (CT) scanning is risky in the diagnosis of epiglottitis, but it may help in the evaluation of complications, such as abscess formation (see the image below), as well as in the exclusion of various conditions, including the presence of a peritonsillar or deep neck space abscess, lingual tonsillitis, or an ingested foreign body. CT scanning should be approached with caution, however, because the supine position increases the risk of acute respiratory distress.

Computed tomography (CT) scan in an adult with acute epiglottitis shows a column of air around the epiglottis (E). The right side is more swollen than the left, and the hypo-attenuating area (A) is suggestive of fluid or the early formation of an abscess.

Computed tomography (CT) scan in an adult with acute epiglottitis shows a column of air around the epiglottis (E). The right side is more swollen than the left, and the hypo-attenuating area (A) is suggestive of fluid or the early formation of an abscess.

The most common CT scan findings include thickening of the epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, platysma muscle, and prevertebral fascia; obliteration of the pre-epiglottic fat planes; and reticulation of the subcutaneous fat. Emphysematous epiglottis is further characterized by soft-tissue lucencies representing gas within a swollen epiglottis. The finding of multiloculated fluid-density collections should raise the suspicion that an abscess exists.

Edema and thickening of the supraglottic tissues with obliteration of the surrounding fat planes can also be seen in patients who have received radiation therapy to the neck. In addition, an enlarged epiglottis can result from a variety of inflammatory and infiltrative disorders, as previously discussed.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

As with CT scanning, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not recommended for initial diagnosis but may be useful for excluding potential mimickers of epiglottitis or for identifying complications. Particular caution should be taken to ensure patient safety, because patients must be supine for a lengthy period of time without direct surveillance.

Few studies have reported MRI findings in acute epiglottitis. T1- and T2-weighted imaging shows thickening of the epiglottis, and there is marked enhancement of the epiglottis and often of the adjacent aryepiglottic folds following gadolinium administration. Areas of nonenhancement may represent necrosis or phlegmon. Cervical lymphadenopathy may also be seen.

Ultrasonography

Recent wide use of ultrasonography in the ED has led to its use in the diagnosis of acute epiglottitis. [17, 18] Studies thus far have been in adults because they have become the much more common patient. Prospectively, using linear phased array, Ko et al have shown that a measurement of the anterior posterior diameter of the epiglottitis was effective in making the diagnosis. [17]

Ultrasound may facilitate exclusion of other diseases, such as peritonsillar abscess, and can help determine results of treatment. The epiglottis is seen as a hypoechoic curvilinear structure, and the thickness of the epiglottis can be measured in a transverse view of the neck just below the hyoid bone. Epiglottitis is strongly indicated If the anterior‐posterior diameters at the right and left edges are greater than 3.6 mm. [19, 20]

-

The normal epiglottis in the image on the right is contrasted with the markedly thickened one on the left. Although the epiglottis is swollen, a column of air can still be seen.

-

Image shows a normal epiglottis in a child; however, the prevertebral space is wide, and retropharyngeal swelling and a retropharyngeal abscess are present. Note the petal-like appearance of the epiglottis and the column of air extending up its midline.

-

Image in a 66-year-old patient with acute epiglottitis. The epiglottis (E) is swollen and its appearance is thumblike rather than petal-like. The aryepiglottic folds (A) also are swollen and are more radiopaque than normal.

-

Computed tomography (CT) scan in an adult with acute epiglottitis shows a column of air around the epiglottis (E). The right side is more swollen than the left, and the hypo-attenuating area (A) is suggestive of fluid or the early formation of an abscess.