Practice Essentials

Pelvic ring fractures typically occur as a result of high-energy trauma, and men are affected more commonly than women. [1] High-energy trauma mechanisms include motorcycle crashes, pedestrian-vehicle crashes, motor vehicle crashes, falls from a height greater than 15 feet, and crush injuries, in descending order of frequency. Motor vehicle crashes are most commonly side-impact collisions when a larger vehicle hits a smaller vehicle. Pelvic ring fractures can also occur from lower-energy mechanisms, including a ground-level fall in elderly osteoporotic patients. [2] Mortality for patients admitted to the hospital with pelvic fractures ranges from 10 to 50%, depending on the presence of life-threatening hemorrhage and associated injuries to the head, chest, and abdomen. [3, 4]

Anatomy and definition

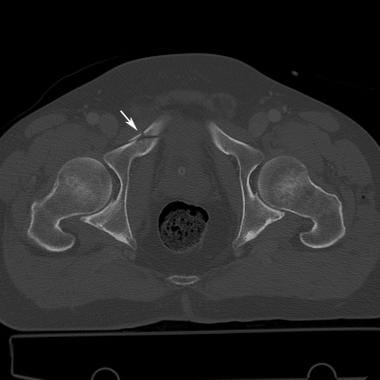

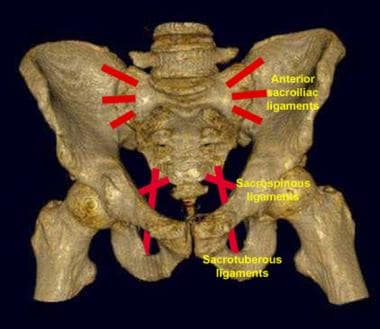

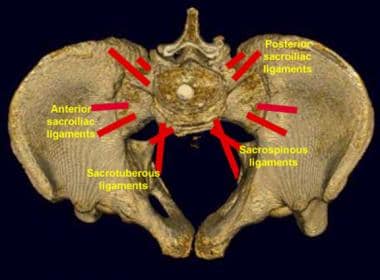

In pelvic ring fractures, the pelvic ring is disrupted anteriorly and posteriorly in 2 or more places. The pelvic ring is composed of 3 bones: the paired innominate bones and the sacrum. The pelvic bones are stabilized by supporting ligaments. These ligaments include ligaments of the symphysis pubis, the anterior and posterior sacroiliac ligaments, the iliolumbar ligaments that attach the transverse processes of L5 to the sacroiliac joint ligaments, the sacrospinous ligaments, and the sacrotuberous ligaments. The ligaments of the symphysis pubis are the weakest, followed by the anterior ligaments of the sacroiliac joints. In unstable injuries, the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments are disrupted and the patient is at risk for vascular and neural injury. [3]

(See the images below.)

Pelvic ligaments as seen on an anterior view of the pelvis. The horizontally oriented anterior sacroiliac and sacrospinous ligaments resist rotation. The vertically oriented sacrotuberous ligaments resist vertical displacement.

Pelvic ligaments as seen on an anterior view of the pelvis. The horizontally oriented anterior sacroiliac and sacrospinous ligaments resist rotation. The vertically oriented sacrotuberous ligaments resist vertical displacement.

Pelvic ligaments as seen on a superior view of the pelvis. The posterior sacroiliac ligaments are the most important structures for pelvic stability.

Pelvic ligaments as seen on a superior view of the pelvis. The posterior sacroiliac ligaments are the most important structures for pelvic stability.

Pelvic ligaments as seen on a posterior view of the pelvis. The short and long posterior sacroiliac ligaments are the most vital structures for the preservation of pelvic ring stability. Note the iliolumbar ligament attachment to the L5 transverse process. An avulsion fracture at this site may be a sign of posterior ligamentous disruption.

Pelvic ligaments as seen on a posterior view of the pelvis. The short and long posterior sacroiliac ligaments are the most vital structures for the preservation of pelvic ring stability. Note the iliolumbar ligament attachment to the L5 transverse process. An avulsion fracture at this site may be a sign of posterior ligamentous disruption.

Clinical and radiologic management

Pelvic ring fractures should be suspected in patients with a suitable mechanism of injury. On physical examination, gentle bilateral compression of the iliac crests reveals tenderness and possibly crepitus. One may observe asymmetry in the alignment of the legs or protrusion of the iliac crests. Some pelvic ring injuries are associated with considerable soft tissue injury over the iliac wings or in the perineum. A pelvic binder or sheet is often placed in the field in at-risk patients to stabilize the pelvis and minimize bleeding. [5, 4]

Initial radiographic examination is a portable pelvic radiograph in the trauma bay. The pelvic binder or sheet may reduce anterior-posterior compression injuries and may be removed briefly for the radiograph at the discretion of the emergency department physician. Evaluation of the sacrum and sacroiliac joints is sometimes limited on portable radiographs. Diastasis of the symphysis pubis of greater than 2.5 cm, obturator ring fractures, and fractures of the transverse processes of L5 that may be associated with avulsion of the iliolumbar ligament are indirect signs of posterior pelvic ring disruption in such cases. [1] On an anteroposterior pelvic radiograph, the normal symphysis pubis measures less than 5 mm. Mild offset of the symphysis pubis of 1-2 mm may be within normal limits. The normal sacroiliac joints measure 2-4 mm. [6, 7]

(See the images below.)

Motorcycle crash. Portable anteroposterior pelvic radiograph demonstrates widening of symphysis pubis 2.8 cm (long arrow) and widening of left sacroiliac joint (short arrow) in keeping with an anterior posterior compression injury (open book). There is also a displaced fracture of the right femoral shaft (arrowhead).

Motorcycle crash. Portable anteroposterior pelvic radiograph demonstrates widening of symphysis pubis 2.8 cm (long arrow) and widening of left sacroiliac joint (short arrow) in keeping with an anterior posterior compression injury (open book). There is also a displaced fracture of the right femoral shaft (arrowhead).

Motorcycle crash with open book injury. Radiograph obtained after application of pelvic binder. There has been reduction of the widened symphysis pubis with mild residual vertical offset (long arrow). Previously identified widening of left sacroiliac joint is no longer seen (short arrow).

Motorcycle crash with open book injury. Radiograph obtained after application of pelvic binder. There has been reduction of the widened symphysis pubis with mild residual vertical offset (long arrow). Previously identified widening of left sacroiliac joint is no longer seen (short arrow).

A hemodynamically unstable patient will also have a focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) ultrasound to look for free intraperitoneal fluid, as well as a diagnostic peritoneal lavage in some trauma centers. [8, 9] If there is gross hemoperitoneum, unstable patients are triaged to the operating room. If there is no gross hemoperitoneum and if there is a pelvic fracture on pelvic radiographs, the patient is triaged to angiography for diagnosis and embolization of bleeding vessels that are assumed to arise from the pelvis.

In a meta-analysis, by Chaijareenont et al, of patients with major pelvic fractures, FAST accurately detected significant intra-abdominal hemorrhage. The pooled sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of FAST in identifying significant intra-abdominal hemorrhage was 79%, 90%, and 93%, respectively. [8] In another study, by Schwed et al, of the use of FAST to detect clinically significant intra-abdominal hemorrhage in over 1200 patients with pelvic fractures, sensitivity was 85.4%, specificity 98.1%, positive predictive value 78.4%, and negative predictive value 98.8%. [9]

Hemodynamically stable patients who are at risk for pelvic ring fracture are evaluated with CT. A whole-body scan, including contrast-enhanced chest, abdomen, and pelvis CT scanning, is performed. A CT cystogram may be performed in stable patients with hematuria, who have a Foley catheter in place.

According to American Urological Association, adult patients with gross hematuria and pelvic fracture should undergo CT cystography, and it is also recommended in cases of pelvic fracture and microhematuria if findings indicate a high risk for bladder injury, such as obturator ring displacement or significant symphysis pubis diastasis. However, CT cystography can expose pediatric patients to radiation exposure; therefore routine use is not recommended in these patients. [10, 11, 12, 13]

CT has replaced radiography in classifying pelvic fractures. With modern multidetector CT, sagittal and coronal reconstructions are acquired in addition to the axial source images. Three-dimensional volume-rendered images can be acquired as well as 3-dimensional maximum-intensity projection images that resemble the traditional inlet and outlet views and Judet views. The inlet projection demonstrates rotational injuries and anterior or posterior displacement of pelvic ring fractures. The outlet projection demonstrates vertical displacement of pelvic ring fractures. Judet views are used to evaluate acetabular fractures.

(See the images below.)

A 15-foot fall. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection image reconstructed from pelvis CT scan. Anteroposterior view.

A 15-foot fall. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection image reconstructed from pelvis CT scan. Anteroposterior view.

A 15-foot fall. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection image reconstructed from pelvis CT scan. Outlet view.

A 15-foot fall. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection image reconstructed from pelvis CT scan. Outlet view.

A 15-foot fall. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection image reconstructed from pelvis CT scan. Inlet view demonstrates the lateral compression injury of the right sacrum and obturator ring (arrows).

A 15-foot fall. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection image reconstructed from pelvis CT scan. Inlet view demonstrates the lateral compression injury of the right sacrum and obturator ring (arrows).

A 15-foot fall. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection image reconstructed from pelvis CT scan. Right internal oblique view/left external oblique view (Judet view).

A 15-foot fall. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection image reconstructed from pelvis CT scan. Right internal oblique view/left external oblique view (Judet view).

A 15-foot fall. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection image reconstructed from pelvis CT scan. Left internal oblique view/right external oblique view (Judet view).

A 15-foot fall. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection image reconstructed from pelvis CT scan. Left internal oblique view/right external oblique view (Judet view).

Contrast-enhanced CT also helps diagnose a pelvic hematoma and active extravasation of contrast. The most serious complication of pelvic ring fractures is life-threatening bleeding. The most common source of hemorrhage is small and medium-sized vessels in fractured cancellous bone, and retroperitoneal hemorrhage is most commonly venous in origin. These sources of bleeding stop on their own with stabilization of the fracture. [14, 15, 16, 17, 18]

Retroperitoneal bleeding occasionally comes from arteries, requiring urgent angiography and embolization. Contrast-enhanced CT can demonstrate active contrast extravasation and can predict the need for angioembolization, with a sensitivity of 66-90%, specificity of 85-98%, and accuracy of 87-98%. [19] The most common sites of arterial bleeding in pelvic fractures are branches of the internal iliac artery (also known as the hypogastric artery), most commonly the internal pudendal and superior gluteal arteries. However, bleeding may also occur from the external iliac artery or its branches. [3, 19]

Multidetector CT (MDCT), which has high spatial resolution and sensitivity and short acquisition times, allows for rapid identification and assessment of pelvic hemorrhage. [20]

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not used to evaluate pelvic ring fractures. MRI is helpful in diagnosing occult fractures, particularly in osteoporotic patients. MRI can show bone marrow edema, cauda and plexus complications, and peripelvic soft tissue damage and may also be valuable for pelvic ring injuries in hemodynamically stable children, adolescents, and young women. [7, 21, 22]

In a study of 60 patients with radiographic signs of an anterior pelvic ring injury, MRI detected posterior pelvic ring fracture in 48. According to the study, 8 cases of posterior pelvic ring fracture would have been missed if only CT had been used. MRI of the pelvis was found to be particularly superior in detecting undislocated fractures in patients with a high incidence of osteoporosis. [23]

Ultrasonography is not used to evaluate pelvic ring fractures. Lower-extremity Doppler ultrasonography is used to assess for the presence of lower-extremity deep venous thrombosis.

Angiography is used to diagnose and treat potentially life-threatening hemorrhage secondary to pelvic ring injury. Pelvic arteriography demonstrates the injured vessels responsible for the hemorrhage. The vessels may then be embolized to control or stop the bleeding.

Classification

Tile and Pennal initially introduced a classification scheme for pelvic fractures in 1979 based on the direction of force. [24] They divided pelvic ring fractures into anteroposterior compression injuries, lateral compression injuries, and vertical shear injuries. Anteroposterior compression injuries were termed “open book fractures.” Lateral compression injuries were subdivided into those that involve the ipsilateral posterior ring and obturator ring, the contralateral posterior ring and obturator ring (“bucket handle fractures”), and posterior ring/bilateral obturator ring injuries. The vertical shear injury was initially described by Malgaigne in 1855 and is due to violent forces with complete disruption of the anterior and posterior ring with vertical displacement.

Tile later modified this classification scheme on the basis of fracture stability. Type A fractures were stable injuries and included isolated fractures of the ilium, ischium, sacrum, or coccyx. Type B fractures were rotationally unstable and included open book and lateral compression injuries alone or in combination. Type B fractures were vertically unstable and included unilateral or bilateral vertically unstable injuries, as well as combination injuries that included a vertically unstable component. [1]

The Young-Burgess classification system was introduced after the Tile system in 1990 and is the system that is most commonly used. [25, 26] It is also based on mechanism of injury. In addition, there is the AO (Arbeitsgemeinschaft fur Osteosynthesefragen) classification of pelvic ring and acetabular fractures. [27, 28, 29] Pelvic fracture classification is performed using plain radiographs and CT scans of the pelvis.

Lateral compression injuries

Lateral compression injuries are due to a lateral compression force such as a side-impact motor vehicle collision or a fall from a height onto one side. In all lateral compression injuries, there are transverse fractures through the pubic rami that may be ipsilateral or contralateral to the side of impact or bilateral.

Lateral compression I injuries have a compression fracture of the sacrum on the side of impact. (See the images below.)

Lateral compression injury as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. Note the characteristic left sacral impaction or buckle fracture (long arrow) and the minimally overlapping left pubic rami fractures (short arrow). The sacral fractures may be subtle on radiographs. Pubic rami fractures may be transversely oriented.

Lateral compression injury as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. Note the characteristic left sacral impaction or buckle fracture (long arrow) and the minimally overlapping left pubic rami fractures (short arrow). The sacral fractures may be subtle on radiographs. Pubic rami fractures may be transversely oriented.

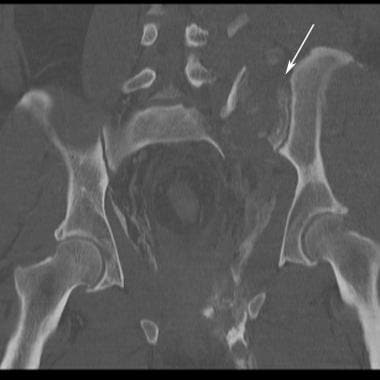

Lateral compression II injuries have a crescent fracture arising from the posterior iliac wing caused by forced internal rotation of the hemipelvis on the affected side with an avulsion fracture of an intact posterior sacroiliac ligament. (See the images below.)

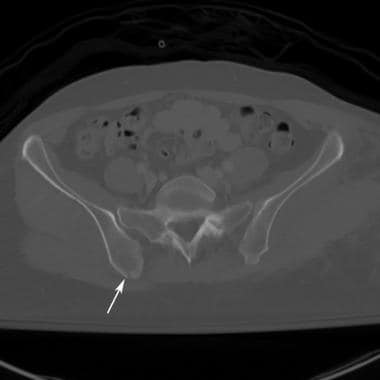

Fall from a horse. Lateral compression II injury. Pelvis CT scan shows a right iliac crescent fracture (arrow).

Fall from a horse. Lateral compression II injury. Pelvis CT scan shows a right iliac crescent fracture (arrow).

Fall from a horse. Lateral compression II injury. CT image a little lower down shows the right iliac crescent fracture entering the sacroiliac joint.

Fall from a horse. Lateral compression II injury. CT image a little lower down shows the right iliac crescent fracture entering the sacroiliac joint.

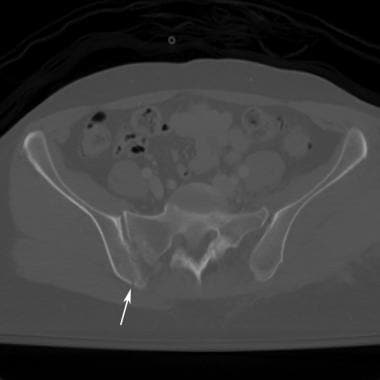

Fall from a horse. Lateral compression II injury. CT lower down shows contralateral obturator ring fracture. This pattern of lateral compression injury may result in marked internal rotation of the right side of the pelvis.

Fall from a horse. Lateral compression II injury. CT lower down shows contralateral obturator ring fracture. This pattern of lateral compression injury may result in marked internal rotation of the right side of the pelvis.

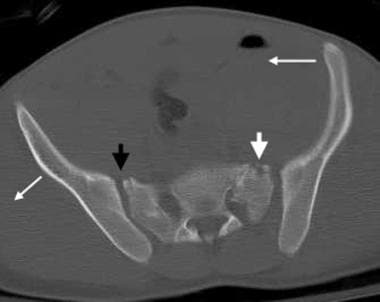

Lateral compression III injuries are the “windswept pelvis.” There is either a compression fracture of the sacrum or an iliac crescent fracture on the side of impact. There is a contralateral anterior compression injury. These injuries typically result from a fall from a height followed by a crush injury, such as a fall from a horse. (See the images below.)

Windswept pelvis or lateral compression III injury as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. The patient had a left lateral compression injury. Note the internal rotation of the left hemipelvis and the overlapping left pubic rami fractures (double arrow). The pubic symphysis diastasis, rightward displacement of the pubic symphysis with external rotation of the right hemipelvis, and right sacroiliac joint diastasis (single arrow) are features of anteroposterior compression. The combination results in the characteristic appearance of the windswept pelvis.

Windswept pelvis or lateral compression III injury as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. The patient had a left lateral compression injury. Note the internal rotation of the left hemipelvis and the overlapping left pubic rami fractures (double arrow). The pubic symphysis diastasis, rightward displacement of the pubic symphysis with external rotation of the right hemipelvis, and right sacroiliac joint diastasis (single arrow) are features of anteroposterior compression. The combination results in the characteristic appearance of the windswept pelvis.

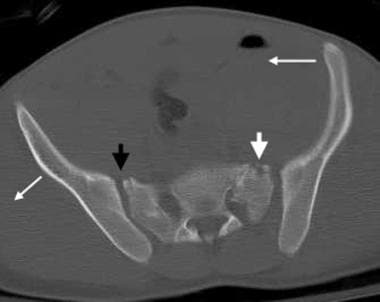

Windswept pelvis or lateral compression III injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. The features of each component of the injury are seen to better advantage with CT. Note the internal rotation of the left hemipelvis and external rotation of the right hemipelvis (long arrows). Note also the left sacral buckle fracture (short white arrow) and the right sacroiliac joint diastasis (short black arrow). The left sacroiliac joint also is disrupted.

Windswept pelvis or lateral compression III injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. The features of each component of the injury are seen to better advantage with CT. Note the internal rotation of the left hemipelvis and external rotation of the right hemipelvis (long arrows). Note also the left sacral buckle fracture (short white arrow) and the right sacroiliac joint diastasis (short black arrow). The left sacroiliac joint also is disrupted.

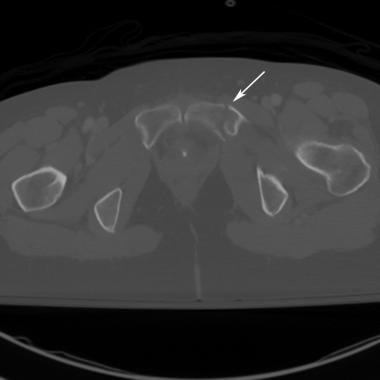

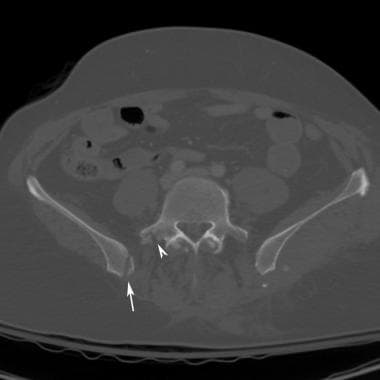

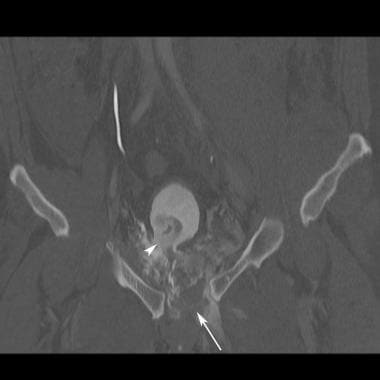

Fall from a horse. Lateral compression III injury. Windswept pelvis. CT of the pelvis shows right iliac crescent fracture (arrow) and fracture of right transverse process of L5 at attachment of iliolumbar ligament (arrowhead).

Fall from a horse. Lateral compression III injury. Windswept pelvis. CT of the pelvis shows right iliac crescent fracture (arrow) and fracture of right transverse process of L5 at attachment of iliolumbar ligament (arrowhead).

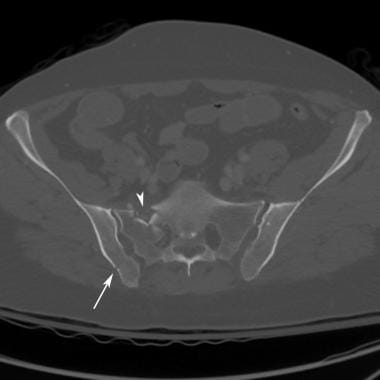

Fall from horse. Lateral compression III injury. Windswept pelvis. CT of the pelvis demonstrates right iliac crescent fracture (arrow) and zone 2 fracture of the right sacral ala that involves the sacral foramen (arrowhead).

Fall from horse. Lateral compression III injury. Windswept pelvis. CT of the pelvis demonstrates right iliac crescent fracture (arrow) and zone 2 fracture of the right sacral ala that involves the sacral foramen (arrowhead).

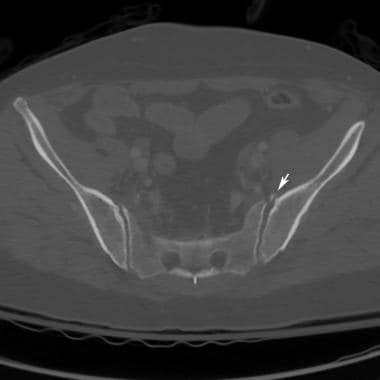

Fall from horse. Lateral compression III injury. Windswept pelvis. CT pelvis demonstrates contralateral widening of anterior left sacroiliac joint with a small avulsion fracture from the sacrum (arrow).

Fall from horse. Lateral compression III injury. Windswept pelvis. CT pelvis demonstrates contralateral widening of anterior left sacroiliac joint with a small avulsion fracture from the sacrum (arrow).

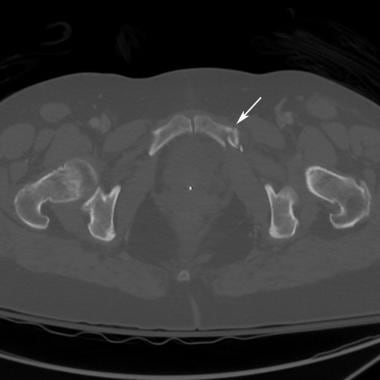

Fall from horse. Lateral compression III injury. Windswept pelvis. CT of the pelvis also demonstrates transverse fracture of left superior pubic ramus (arrow). Fracture of left inferior pubic ramus is not shown.

Fall from horse. Lateral compression III injury. Windswept pelvis. CT of the pelvis also demonstrates transverse fracture of left superior pubic ramus (arrow). Fracture of left inferior pubic ramus is not shown.

Anteroposterior compression injuries

Anteroposterior compression injuries are due to a direct blow to the anterior pelvis or forced external rotation of the legs, as may be seen in motorcycle crashes. In all cases, there is either diastasis of the pubic symphysis or a vertical fracture through the pubic rami. There is increased pelvic volume. The posterior fracture differentiates the subtypes of anteroposterior compression injuries.

Anteroposterior compression I injuries are stretch injuries of the anterior sacroiliac ligament without disruption. There is mild widening of the symphysis pubis, less than 1-2 cm, and there may be mild widening of the anterior sacroiliac joint on one side. These are stable injuries.

Anteroposterior compression II injuries occur with tearing of the anterior sacroiliac ligament and disruption of the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments. They result in an “open book pelvis” that is rotationally unstable but vertically stable because of intact posterior sacroiliac ligaments. There is obvious widening of the anterior sacroiliac joint. The symphysis pubis is typically widened greater than 2.5 cm. [1] (See the image below.)

Anteroposterior compression injury as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. The symphysis pubis is wider than 2.5 cm (double arrow). The right sacroiliac joint is diastatic (single arrow). This is at least an anteroposterior compression II injury.

Anteroposterior compression injury as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. The symphysis pubis is wider than 2.5 cm (double arrow). The right sacroiliac joint is diastatic (single arrow). This is at least an anteroposterior compression II injury.

Anteroposterior compression III injuries result in complete separation of the hemipelvis. There is disruption of the anterior and posterior sacroiliac ligaments, as well as disruption of the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments. The pelvis is rotationally and vertically unstable. However, there is no vertical offset of the hemipelvis, distinguishing this injury from vertical shear injuries. (See the images below.)

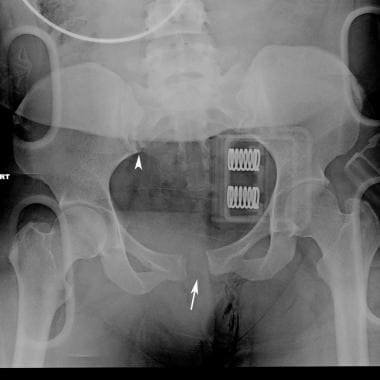

Motor vehicle crash. Car versus guardrail. Portable pelvic radiograph obtained with binder in place demonstrates widening of symphysis pubis (arrow) and widening of right sacroiliac joint (arrowhead). Left sacroiliac joint is difficult to evaluate because of the binder.

Motor vehicle crash. Car versus guardrail. Portable pelvic radiograph obtained with binder in place demonstrates widening of symphysis pubis (arrow) and widening of right sacroiliac joint (arrowhead). Left sacroiliac joint is difficult to evaluate because of the binder.

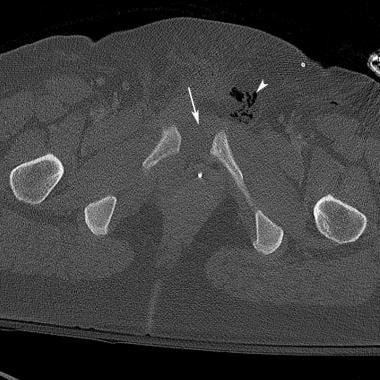

Motor vehicle crash. Car versus guardrail. CT of the pelvis demonstrates widening of bilateral anterior sacroiliac joints (arrowheads). There is posterior offset of the right sacroiliac joint (arrow) that indicates posterior ligament disruption. This is a right anteroposterior compression III and left anteroposterior compression II open book injury.

Motor vehicle crash. Car versus guardrail. CT of the pelvis demonstrates widening of bilateral anterior sacroiliac joints (arrowheads). There is posterior offset of the right sacroiliac joint (arrow) that indicates posterior ligament disruption. This is a right anteroposterior compression III and left anteroposterior compression II open book injury.

Motor vehicle crash. Car versus guardrail. CT pelvis demonstrates widening of the symphysis pubis (arrow). Patient sustained bilateral anteroposterior compression injuries, right anteroposterior compression III and left anteroposterior compression II. Patient also sustained an open soft tissue injury to the left groin (arrowhead).

Motor vehicle crash. Car versus guardrail. CT pelvis demonstrates widening of the symphysis pubis (arrow). Patient sustained bilateral anteroposterior compression injuries, right anteroposterior compression III and left anteroposterior compression II. Patient also sustained an open soft tissue injury to the left groin (arrowhead).

Anteroposterior (AP) compression injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. The location and degree of sacroiliac disruption is better seen on CT scans than on radiographs. The external rotation of the right hemipelvis is a characteristic finding in AP compression. Slight posterior displacement of the iliac side of the right sacroiliac joint suggests ligamentous disruption (arrow). This represents a type III AP compression injury.

Anteroposterior (AP) compression injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. The location and degree of sacroiliac disruption is better seen on CT scans than on radiographs. The external rotation of the right hemipelvis is a characteristic finding in AP compression. Slight posterior displacement of the iliac side of the right sacroiliac joint suggests ligamentous disruption (arrow). This represents a type III AP compression injury.

Vertical shear injuries

Vertical shear injuries are due to a strong vertical force on an unstable pelvis, such as a fall from a height or ejection from a motorcycle. There is either disruption of the symphysis pubis or vertical fractures through pubic rami on one or both sides. The posterior pelvic ring is disrupted vertically, either through the sacroiliac joint or through fractures of the sacrum or iliac wing. There is vertical offset of the hemipelvis. Vertical shear injuries may be unilateral or bilateral.

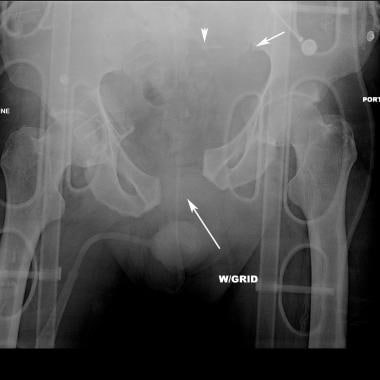

The best way to evaluate for vertical instability is to look at the posterior pelvic ring. Vertical offset of the symphysis pubis may be due to rotation of a leg from lateral compression or anteroposterior compression injuries or a floating symphysis. In particular, the lateral compression II injury can result in shortening of a leg that is corrected by externally rotating the pelvis. On plain radiographs and CT scans, it is best to evaluate the inferior margin of the sacroiliac joint to determine if there is vertical offset. [1] (See the images below.)

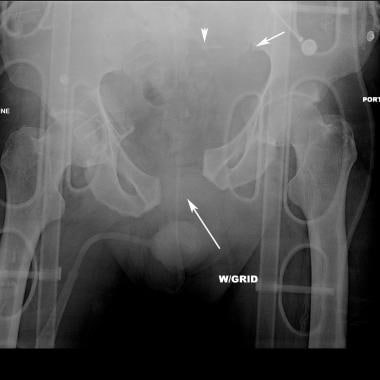

Fall from overpass. Portable pelvic radiograph demonstrates a zone 2 fracture of the left sacrum that involves sacral foramina (arrowhead). There is vertical displacement of the left hemipelvis at the inferior margin of the left sacroiliac joint (short arrow). There is widening of the symphysis pubis with vertical offset (long arrow). This represents a vertical shear injury.

Fall from overpass. Portable pelvic radiograph demonstrates a zone 2 fracture of the left sacrum that involves sacral foramina (arrowhead). There is vertical displacement of the left hemipelvis at the inferior margin of the left sacroiliac joint (short arrow). There is widening of the symphysis pubis with vertical offset (long arrow). This represents a vertical shear injury.

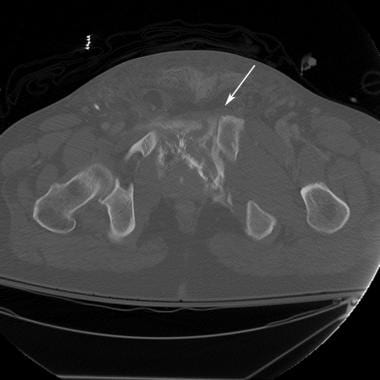

Fall from overpass. CT pelvis demonstrates zone 2 fracture of left sacrum that is widely separated (arrow) in this vertical shear injury.

Fall from overpass. CT pelvis demonstrates zone 2 fracture of left sacrum that is widely separated (arrow) in this vertical shear injury.

Fall from overpass. CT pelvis demonstrates widening of the symphysis pubis with anterior displacement of left hemipelvis in this vertical shear injury (arrow). There is also extravasated contrast from the urinary bladder from extraperitoneal bladder rupture. Patient also has a large pelvic hematoma and bilateral internal iliac arteries were embolized before CT.

Fall from overpass. CT pelvis demonstrates widening of the symphysis pubis with anterior displacement of left hemipelvis in this vertical shear injury (arrow). There is also extravasated contrast from the urinary bladder from extraperitoneal bladder rupture. Patient also has a large pelvic hematoma and bilateral internal iliac arteries were embolized before CT.

Fall from overpass. Coronal reconstructions from CT of the pelvis demonstrate zone 2 fracture of the left sacrum with vertical displacement of the left hemipelvis in this vertical shear injury (arrow).

Fall from overpass. Coronal reconstructions from CT of the pelvis demonstrate zone 2 fracture of the left sacrum with vertical displacement of the left hemipelvis in this vertical shear injury (arrow).

Fall from overpass. Coronal reconstruction from CT of the pelvis demonstrates widening of the symphysis pubis with vertical offset (arrow). There is extraperitoneal bladder rupture with a defect at the right bladder base and extravasated urinary contrast (arrowhead). Hematoma exerts mass effect on the bladder. Patient is catheterized and had a CT cystogram.

Fall from overpass. Coronal reconstruction from CT of the pelvis demonstrates widening of the symphysis pubis with vertical offset (arrow). There is extraperitoneal bladder rupture with a defect at the right bladder base and extravasated urinary contrast (arrowhead). Hematoma exerts mass effect on the bladder. Patient is catheterized and had a CT cystogram.

Fall from overpass. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection in the outlet projection reconstructed from CT of the pelvis demonstrates the vertical displacement of the left hemipelvis in this vertical shear injury (arrow).

Fall from overpass. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection in the outlet projection reconstructed from CT of the pelvis demonstrates the vertical displacement of the left hemipelvis in this vertical shear injury (arrow).

Fall from overpass. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection in the inlet projection reconstructed from CT of the pelvis demonstrates posterior displacement of left hemipelvis in this vertical shear injury (arrow). Extravasated contrast from the urinary bladder from extraperitoneal bladder rupture is also seen (arrowhead). Hematoma exerts mass effect on the bladder.

Fall from overpass. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection in the inlet projection reconstructed from CT of the pelvis demonstrates posterior displacement of left hemipelvis in this vertical shear injury (arrow). Extravasated contrast from the urinary bladder from extraperitoneal bladder rupture is also seen (arrowhead). Hematoma exerts mass effect on the bladder.

Vertical shear injury as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. The left hemipelvis is displaced in a cranial direction with associated sacroiliac joint diastasis (long arrow). The vertically oriented fractures of the pubic rami usually are ipsilateral; however, in this patient, the rami fractures are contralateral (short arrow).

Vertical shear injury as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. The left hemipelvis is displaced in a cranial direction with associated sacroiliac joint diastasis (long arrow). The vertically oriented fractures of the pubic rami usually are ipsilateral; however, in this patient, the rami fractures are contralateral (short arrow).

Vertical shear injury as seen on an outlet radiograph of the pelvis. The vertical (cranial) displacement of the left hemipelvis and pubic symphysis is better visualized by using the outlet view. In addition, a left iliac fracture is more readily apparent (large arrows). Left sacroiliac joint diastasis is seen (small arrow). Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection images constructed from CT now replace inlet and outlet views of the pelvis.

Vertical shear injury as seen on an outlet radiograph of the pelvis. The vertical (cranial) displacement of the left hemipelvis and pubic symphysis is better visualized by using the outlet view. In addition, a left iliac fracture is more readily apparent (large arrows). Left sacroiliac joint diastasis is seen (small arrow). Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection images constructed from CT now replace inlet and outlet views of the pelvis.

Vertical shear injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. A displaced vertically oriented fracture of the ilium extends to the left sacroiliac joint.

Vertical shear injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. A displaced vertically oriented fracture of the ilium extends to the left sacroiliac joint.

Vertical shear injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. A slightly more inferior image demonstrates anterior and posterior disruption of the left sacroiliac joint. The left hemipelvis is rotationally and vertically unstable.

Vertical shear injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. A slightly more inferior image demonstrates anterior and posterior disruption of the left sacroiliac joint. The left hemipelvis is rotationally and vertically unstable.

Vertical shear injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. A vertically oriented fracture of the right superior pubic ramus is depicted with cranial displacement of the pubic symphysis and left hemipelvis.

Vertical shear injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. A vertically oriented fracture of the right superior pubic ramus is depicted with cranial displacement of the pubic symphysis and left hemipelvis.

Combination mechanisms

The combination mechanism category of injury includes those injury subtypes that share features of lateral compression, anteroposterior compression, and vertical shear injuries, such as the lateral compression/vertical shear and the anteroposterior compression/vertical shear combinations.

The Young-Burgess classification scheme for pelvic ring injury enables radiologists to recognize patterns of injury, improving detection of posterior pelvic ring injures. It also serves as a guide for surgical versus conservative therapy. More serious injuries are generally associated with increased mortality from life-threatening hemorrhage and associated injuries.

Complications of pelvic ring fractures

The most serious complication of pelvic ring injuries is life-threatening hemorrhage. Although the risk of hemorrhage increases with increasing injury severity, the Young-Burgess classification scheme for pelvic ring injury cannot be used to guide transfusion requirements and the need for angiography and embolization in individual cases. Some patients with high-grade pelvic ring injuries do not have significant bleeding, whereas other patients with low-grade pelvic ring injuries experience life-threatening hemorrhage. [30, 31] Geriatric patients in particular may experience life-threatening hemorrhage from relatively stable lateral compression injuries following minor trauma, in part due to atherosclerosis resulting in impaired vasoconstriction and somewhat loose periosteum. [31]

Other complications of pelvic ring fractures are nerve injuries, particularly with sacral fractures. Sacral fractures are classified by the system of Denis. [32] Zone 1 fractures of the sacral ala do not involve the neural foramina and may be associated with L5 nerve root injury. Zone 2 fractures involve the sacral foramina and may result in sciatica or, less commonly, bladder dysfunction. Zone 3 fractures involve the sacral spinal canal and may result in cauda equina syndrome with saddle anesthesia and loss of sphincter tone. [32]

Pelvic ring fractures are associated with injury to the bladder or urethra in 15-20% of cases. [3] Men are affected more commonly than women. Ninety-five percent of bladder injuries have gross hematuria, and the remaining 5% have microscopic hematuria. [3] Urethral injury should be suspected in men who have blood at the meatus, perineal bruising, a mobile prostate gland on physical examination, inability to pass urine, or inability to pass a Foley catheter. If urethral injury is suspected, a retrograde urethrogram is performed.

The British Orthopaedic Association Standards for Trauma (BOAST) includes the following recommendations for the treatment of urologic injury associated with pelvic fractures [33] :

-

Intraperitoneal bladder rupture: Direct repair via emergency laparotomy

-

Extraperitoneal bladder rupture: Catheter drainage alone; for patients with unstable pelvic fracture, fracture reduction and fixation should be performed at the time of the primary repair of the bladder.

-

Extraperitoneal rupture of the bladder neck: Primary repair.

-

Bladder injuries identified during pelvic fracture surgery: Immediate repair during surgery with bladder drainage (via urethral or suprapubic catheter, as appropriate).

According to the BOAST guidelines, the indications for primary (within 48 hours) urethral repair are as follows [33] :

-

Associated anorectal injury

-

Perineal degloving

-

Bladder neck injury

-

Massive bladder displacement

-

Penetrating trauma to the anterior urethra.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is another possible complication of a pelvic fracture and is attributed to prolonged period of inactivity, damage to the vascular endothelia, and surgical intervention. [34]

Long-term complications of pelvic ring fractures include chronic pain, painful gait, and sexual dysfunction. Many women who sustain pelvic ring fractures who later become pregnant deliver by cesarean delivery. [5]

Treatment of pelvic fractures

Treatment of pelvic fractures requires an understanding of the injury and pattern of instability. The posterior pelvic ring injury defines ultimate stability.

The pelvic sheet or binder should be removed within 36 hours to prevent pressure necrosis of the skin. An external fixation device may be placed anteriorly, or a pelvic C clamp may be placed posteriorly. Modern surgical methods are enabling percutaneous reduction and fixation of pelvic fractures under fluoroscopic guidance. Percutaneous nails may be placed across the sacroiliac joints and along the anterior column of the acetabulum in some cases. Open reduction and traditional malleable plate and screw fixation are still needed in some cases. [3, 5]

With complete instability of the posterior ring (vertically unstable injuries with disruption of the posterior sacroiliac ligament or complete fractures through the sacrum and sacroiliac joints), patients need posterior stabilization with supplemental anterior stabilization. With partial instability of the pelvic ring (rotationally unstable injuries without disruption of the posterior SI ligament), anterior stabilization alone may be adequate. With posterior iliac crescent injuries, which are essentially an avulsion of the posterior sacroiliac ligament, posterior stabilization is required. [3, 5]

Computed Tomography

All radiographic findings should be further assessed on pelvic CT scans, because subtle fractures and disruptions may be more apparent on CT scans. In particular, sacral fractures may be difficult to detect on radiographs. The spatial relationship of fracture fragments is often easier to assess with CT scans than with radiographs. Axial CT images may be reformatted into the coronal and sagittal planes. Three-dimensional (3-D)images of the pelvis may also be reconstructed. Studies support the use of 3D intraoperative imaging because of decreased rates in misplaced implants, malreduced fractures, complications, and need for revision. [35, 36] Reformatted images are more useful in assessing acetabular fractures than in evaluating pelvic ring fractures.

(See the images below.)

Anteroposterior (AP) compression injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. The location and degree of sacroiliac disruption is better seen on CT scans than on radiographs. The external rotation of the right hemipelvis is a characteristic finding in AP compression. Slight posterior displacement of the iliac side of the right sacroiliac joint suggests ligamentous disruption (arrow). This represents a type III AP compression injury.

Anteroposterior (AP) compression injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. The location and degree of sacroiliac disruption is better seen on CT scans than on radiographs. The external rotation of the right hemipelvis is a characteristic finding in AP compression. Slight posterior displacement of the iliac side of the right sacroiliac joint suggests ligamentous disruption (arrow). This represents a type III AP compression injury.

Lateral compression injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. The left sacral buckle (anterior crush) fracture is more readily apparent on the CT scan than on other images.

Lateral compression injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. The left sacral buckle (anterior crush) fracture is more readily apparent on the CT scan than on other images.

Windswept pelvis or lateral compression III injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. The features of each component of the injury are seen to better advantage with CT. Note the internal rotation of the left hemipelvis and external rotation of the right hemipelvis (long arrows). Note also the left sacral buckle fracture (short white arrow) and the right sacroiliac joint diastasis (short black arrow). The left sacroiliac joint also is disrupted.

Windswept pelvis or lateral compression III injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. The features of each component of the injury are seen to better advantage with CT. Note the internal rotation of the left hemipelvis and external rotation of the right hemipelvis (long arrows). Note also the left sacral buckle fracture (short white arrow) and the right sacroiliac joint diastasis (short black arrow). The left sacroiliac joint also is disrupted.

Vertical shear injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. A displaced vertically oriented fracture of the ilium extends to the left sacroiliac joint.

Vertical shear injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. A displaced vertically oriented fracture of the ilium extends to the left sacroiliac joint.

Vertical shear injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. A slightly more inferior image demonstrates anterior and posterior disruption of the left sacroiliac joint. The left hemipelvis is rotationally and vertically unstable.

Vertical shear injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. A slightly more inferior image demonstrates anterior and posterior disruption of the left sacroiliac joint. The left hemipelvis is rotationally and vertically unstable.

Vertical shear injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. A vertically oriented fracture of the right superior pubic ramus is depicted with cranial displacement of the pubic symphysis and left hemipelvis.

Vertical shear injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. A vertically oriented fracture of the right superior pubic ramus is depicted with cranial displacement of the pubic symphysis and left hemipelvis.

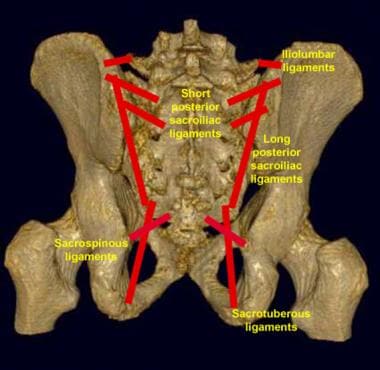

Diastasis of the symphysis pubis, which most commonly indicates an anteroposterior compression injury.

Diastasis of the symphysis pubis, which most commonly indicates an anteroposterior compression injury.

Avulsion fractures of the pelvis (eg, from the anterior inferior aspect of the iliac spine) do not affect the integrity of the pelvic ring. Isolated iliac wing fractures may occur as a result of a direct blow without disruption of the pelvic ring. With iliac crest, anterior iliac spine, and ischial tuberosity avulsion fractures, the integrity of the pelvic ring is also maintained.

Avulsion fractures of the pelvis (eg, from the anterior inferior aspect of the iliac spine) do not affect the integrity of the pelvic ring. Isolated iliac wing fractures may occur as a result of a direct blow without disruption of the pelvic ring. With iliac crest, anterior iliac spine, and ischial tuberosity avulsion fractures, the integrity of the pelvic ring is also maintained.

In addition to the osseous structures, the soft tissues of the pelvis should be examined. The size of a pelvic hematoma secondary to a pelvic ring fracture may be determined. If contrast material is intravenously administered for pelvic CT, active arterial bleeding may be demonstrated, and the information may be used to guide the clinical decision to incorporate angiography into the patient's treatment plan.

Borror et al calculated the total volumetric rate of abdominopelvic bleeding in 29 patients with acute pelvic fractures using CT images and found that an abdominopelvic bleed rate >20 ml/min was associated with a mortality of 80% and a rate < 20 ml/min was associated with a 92% survival rate. [17]

The use of pelvic CT scans with axial source images and coronal and sagittal reformations allows accurate classification of pelvic ring fractures in virtually every patient. Three-dimensional volume-rendered images and 3-dimensional maximum-intensity projection images reconstructed from the CT data further add to the radiologist's ability to accurately classify injuries and assist orthopedic surgeons in operative planning.

Manual detection of pelvic fracture from CT images may be challenging because of low resolution and complex pelvic structures. According to Wu et al, automated fracture detection from segmented bones can help analyze pelvic CT images and detect severity of injuries. [37]

In a study of 72 patients who underwent abdominal CT and pelvic CT within a 2-week period to evaluate pelvic fractures, abdominal CT alone was found in many cases to provide sufficient detection of pelvic fractures. [38]

Radiography

Initial radiographic examination is a portable pelvic radiograph in the trauma bay. The pelvic binder or sheet may reduce anterior-posterior compression injuries and may be removed briefly for the radiograph at the discretion of the emergency department physician. Evaluation of the sacrum and sacroiliac joints is sometimes limited on portable radiographs. Diastasis of the symphysis pubis of greater than 2.5 cm, obturator ring fractures, and fractures of the transverse processes of L5 that may be associated with avulsion of the iliolumbar ligament are indirect signs of posterior pelvic ring disruption in such cases. [1] On an anteroposterior pelvic radiograph, the normal symphysis pubis measures less than 5 mm. Mild offset of the symphysis pubis of 1-2 mm may be within normal limits. The normal sacroiliac joints measure 2-4 mm. [6]

CT has replaced radiography in classifying pelvic fractures. With modern multidetector CT, sagittal and coronal reconstructions are acquired in addition to the axial source images. Three-dimensional volume-rendered images can be acquired as well as 3-dimensional maximum-intensity projection images that resemble the traditional inlet and outlet views and Judet views.

(See the images below.)

Motorcycle crash. Portable anteroposterior pelvic radiograph demonstrates widening of symphysis pubis 2.8 cm (long arrow) and widening of left sacroiliac joint (short arrow) in keeping with an anterior posterior compression injury (open book). There is also a displaced fracture of the right femoral shaft (arrowhead).

Motorcycle crash. Portable anteroposterior pelvic radiograph demonstrates widening of symphysis pubis 2.8 cm (long arrow) and widening of left sacroiliac joint (short arrow) in keeping with an anterior posterior compression injury (open book). There is also a displaced fracture of the right femoral shaft (arrowhead).

Motorcycle crash with open book injury. Radiograph obtained after application of pelvic binder. There has been reduction of the widened symphysis pubis with mild residual vertical offset (long arrow). Previously identified widening of left sacroiliac joint is no longer seen (short arrow).

Motorcycle crash with open book injury. Radiograph obtained after application of pelvic binder. There has been reduction of the widened symphysis pubis with mild residual vertical offset (long arrow). Previously identified widening of left sacroiliac joint is no longer seen (short arrow).

Lateral compression injury as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. Note the characteristic left sacral impaction or buckle fracture (long arrow) and the minimally overlapping left pubic rami fractures (short arrow). The sacral fractures may be subtle on radiographs. Pubic rami fractures may be transversely oriented.

Lateral compression injury as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. Note the characteristic left sacral impaction or buckle fracture (long arrow) and the minimally overlapping left pubic rami fractures (short arrow). The sacral fractures may be subtle on radiographs. Pubic rami fractures may be transversely oriented.

Windswept pelvis or lateral compression III injury as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. The patient had a left lateral compression injury. Note the internal rotation of the left hemipelvis and the overlapping left pubic rami fractures (double arrow). The pubic symphysis diastasis, rightward displacement of the pubic symphysis with external rotation of the right hemipelvis, and right sacroiliac joint diastasis (single arrow) are features of anteroposterior compression. The combination results in the characteristic appearance of the windswept pelvis.

Windswept pelvis or lateral compression III injury as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. The patient had a left lateral compression injury. Note the internal rotation of the left hemipelvis and the overlapping left pubic rami fractures (double arrow). The pubic symphysis diastasis, rightward displacement of the pubic symphysis with external rotation of the right hemipelvis, and right sacroiliac joint diastasis (single arrow) are features of anteroposterior compression. The combination results in the characteristic appearance of the windswept pelvis.

Fall from overpass. Portable pelvic radiograph demonstrates a zone 2 fracture of the left sacrum that involves sacral foramina (arrowhead). There is vertical displacement of the left hemipelvis at the inferior margin of the left sacroiliac joint (short arrow). There is widening of the symphysis pubis with vertical offset (long arrow). This represents a vertical shear injury.

Fall from overpass. Portable pelvic radiograph demonstrates a zone 2 fracture of the left sacrum that involves sacral foramina (arrowhead). There is vertical displacement of the left hemipelvis at the inferior margin of the left sacroiliac joint (short arrow). There is widening of the symphysis pubis with vertical offset (long arrow). This represents a vertical shear injury.

Vertical shear injury as seen on an outlet radiograph of the pelvis. The vertical (cranial) displacement of the left hemipelvis and pubic symphysis is better visualized by using the outlet view. In addition, a left iliac fracture is more readily apparent (large arrows). Left sacroiliac joint diastasis is seen (small arrow). Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection images constructed from CT now replace inlet and outlet views of the pelvis.

Vertical shear injury as seen on an outlet radiograph of the pelvis. The vertical (cranial) displacement of the left hemipelvis and pubic symphysis is better visualized by using the outlet view. In addition, a left iliac fracture is more readily apparent (large arrows). Left sacroiliac joint diastasis is seen (small arrow). Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection images constructed from CT now replace inlet and outlet views of the pelvis.

Iliac wing fracture as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. A fracture of the left iliac wing occurred secondary to a direct blow to the left hemipelvis. The fracture does not involve the pelvic ring; therefore, the pelvis is stable.

Iliac wing fracture as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. A fracture of the left iliac wing occurred secondary to a direct blow to the left hemipelvis. The fracture does not involve the pelvic ring; therefore, the pelvis is stable.

-

Pelvic ligaments as seen on an anterior view of the pelvis. The horizontally oriented anterior sacroiliac and sacrospinous ligaments resist rotation. The vertically oriented sacrotuberous ligaments resist vertical displacement.

-

Pelvic ligaments as seen on a superior view of the pelvis. The posterior sacroiliac ligaments are the most important structures for pelvic stability.

-

Pelvic ligaments as seen on a posterior view of the pelvis. The short and long posterior sacroiliac ligaments are the most vital structures for the preservation of pelvic ring stability. Note the iliolumbar ligament attachment to the L5 transverse process. An avulsion fracture at this site may be a sign of posterior ligamentous disruption.

-

Motorcycle crash. Portable anteroposterior pelvic radiograph demonstrates widening of symphysis pubis 2.8 cm (long arrow) and widening of left sacroiliac joint (short arrow) in keeping with an anterior posterior compression injury (open book). There is also a displaced fracture of the right femoral shaft (arrowhead).

-

Motorcycle crash with open book injury. Radiograph obtained after application of pelvic binder. There has been reduction of the widened symphysis pubis with mild residual vertical offset (long arrow). Previously identified widening of left sacroiliac joint is no longer seen (short arrow).

-

A 15-foot fall. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection image reconstructed from pelvis CT scan. Anteroposterior view.

-

A 15-foot fall. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection image reconstructed from pelvis CT scan. Outlet view.

-

A 15-foot fall. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection image reconstructed from pelvis CT scan. Inlet view demonstrates the lateral compression injury of the right sacrum and obturator ring (arrows).

-

A 15-foot fall. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection image reconstructed from pelvis CT scan. Right internal oblique view/left external oblique view (Judet view).

-

A 15-foot fall. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection image reconstructed from pelvis CT scan. Left internal oblique view/right external oblique view (Judet view).

-

Lateral compression injury as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. Note the characteristic left sacral impaction or buckle fracture (long arrow) and the minimally overlapping left pubic rami fractures (short arrow). The sacral fractures may be subtle on radiographs. Pubic rami fractures may be transversely oriented.

-

A 15-foot fall. Lateral compression I injury. Zone 1 impaction fracture of the right sacral ala.

-

A 15-foot fall. Lateral compression I injury. Transverse fracture of right superior pubic ramus.

-

Fall from a horse. Lateral compression II injury. Pelvis CT scan shows a right iliac crescent fracture (arrow).

-

Fall from a horse. Lateral compression II injury. CT image a little lower down shows the right iliac crescent fracture entering the sacroiliac joint.

-

Fall from a horse. Lateral compression II injury. CT lower down shows contralateral obturator ring fracture. This pattern of lateral compression injury may result in marked internal rotation of the right side of the pelvis.

-

Windswept pelvis or lateral compression III injury as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. The patient had a left lateral compression injury. Note the internal rotation of the left hemipelvis and the overlapping left pubic rami fractures (double arrow). The pubic symphysis diastasis, rightward displacement of the pubic symphysis with external rotation of the right hemipelvis, and right sacroiliac joint diastasis (single arrow) are features of anteroposterior compression. The combination results in the characteristic appearance of the windswept pelvis.

-

Windswept pelvis or lateral compression III injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. The features of each component of the injury are seen to better advantage with CT. Note the internal rotation of the left hemipelvis and external rotation of the right hemipelvis (long arrows). Note also the left sacral buckle fracture (short white arrow) and the right sacroiliac joint diastasis (short black arrow). The left sacroiliac joint also is disrupted.

-

Fall from a horse. Lateral compression III injury. Windswept pelvis. CT of the pelvis shows right iliac crescent fracture (arrow) and fracture of right transverse process of L5 at attachment of iliolumbar ligament (arrowhead).

-

Fall from horse. Lateral compression III injury. Windswept pelvis. CT of the pelvis demonstrates right iliac crescent fracture (arrow) and zone 2 fracture of the right sacral ala that involves the sacral foramen (arrowhead).

-

Fall from horse. Lateral compression III injury. Windswept pelvis. CT pelvis demonstrates contralateral widening of anterior left sacroiliac joint with a small avulsion fracture from the sacrum (arrow).

-

Fall from horse. Lateral compression III injury. Windswept pelvis. CT of the pelvis also demonstrates transverse fracture of left superior pubic ramus (arrow). Fracture of left inferior pubic ramus is not shown.

-

Anteroposterior compression injury as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. The symphysis pubis is wider than 2.5 cm (double arrow). The right sacroiliac joint is diastatic (single arrow). This is at least an anteroposterior compression II injury.

-

Motor vehicle crash. Car versus guardrail. Portable pelvic radiograph obtained with binder in place demonstrates widening of symphysis pubis (arrow) and widening of right sacroiliac joint (arrowhead). Left sacroiliac joint is difficult to evaluate because of the binder.

-

Motor vehicle crash. Car versus guardrail. CT of the pelvis demonstrates widening of bilateral anterior sacroiliac joints (arrowheads). There is posterior offset of the right sacroiliac joint (arrow) that indicates posterior ligament disruption. This is a right anteroposterior compression III and left anteroposterior compression II open book injury.

-

Motor vehicle crash. Car versus guardrail. CT pelvis demonstrates widening of the symphysis pubis (arrow). Patient sustained bilateral anteroposterior compression injuries, right anteroposterior compression III and left anteroposterior compression II. Patient also sustained an open soft tissue injury to the left groin (arrowhead).

-

Anteroposterior (AP) compression injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. The location and degree of sacroiliac disruption is better seen on CT scans than on radiographs. The external rotation of the right hemipelvis is a characteristic finding in AP compression. Slight posterior displacement of the iliac side of the right sacroiliac joint suggests ligamentous disruption (arrow). This represents a type III AP compression injury.

-

Fall from overpass. Portable pelvic radiograph demonstrates a zone 2 fracture of the left sacrum that involves sacral foramina (arrowhead). There is vertical displacement of the left hemipelvis at the inferior margin of the left sacroiliac joint (short arrow). There is widening of the symphysis pubis with vertical offset (long arrow). This represents a vertical shear injury.

-

Fall from overpass. CT pelvis demonstrates zone 2 fracture of left sacrum that is widely separated (arrow) in this vertical shear injury.

-

Fall from overpass. CT pelvis demonstrates widening of the symphysis pubis with anterior displacement of left hemipelvis in this vertical shear injury (arrow). There is also extravasated contrast from the urinary bladder from extraperitoneal bladder rupture. Patient also has a large pelvic hematoma and bilateral internal iliac arteries were embolized before CT.

-

Fall from overpass. Coronal reconstructions from CT of the pelvis demonstrate zone 2 fracture of the left sacrum with vertical displacement of the left hemipelvis in this vertical shear injury (arrow).

-

Fall from overpass. Coronal reconstruction from CT of the pelvis demonstrates widening of the symphysis pubis with vertical offset (arrow). There is extraperitoneal bladder rupture with a defect at the right bladder base and extravasated urinary contrast (arrowhead). Hematoma exerts mass effect on the bladder. Patient is catheterized and had a CT cystogram.

-

Fall from overpass. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection in the outlet projection reconstructed from CT of the pelvis demonstrates the vertical displacement of the left hemipelvis in this vertical shear injury (arrow).

-

Fall from overpass. Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection in the inlet projection reconstructed from CT of the pelvis demonstrates posterior displacement of left hemipelvis in this vertical shear injury (arrow). Extravasated contrast from the urinary bladder from extraperitoneal bladder rupture is also seen (arrowhead). Hematoma exerts mass effect on the bladder.

-

Vertical shear injury as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. The left hemipelvis is displaced in a cranial direction with associated sacroiliac joint diastasis (long arrow). The vertically oriented fractures of the pubic rami usually are ipsilateral; however, in this patient, the rami fractures are contralateral (short arrow).

-

Vertical shear injury as seen on an outlet radiograph of the pelvis. The vertical (cranial) displacement of the left hemipelvis and pubic symphysis is better visualized by using the outlet view. In addition, a left iliac fracture is more readily apparent (large arrows). Left sacroiliac joint diastasis is seen (small arrow). Three-dimensional maximum-intensity projection images constructed from CT now replace inlet and outlet views of the pelvis.

-

Vertical shear injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. A displaced vertically oriented fracture of the ilium extends to the left sacroiliac joint.

-

Vertical shear injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. A slightly more inferior image demonstrates anterior and posterior disruption of the left sacroiliac joint. The left hemipelvis is rotationally and vertically unstable.

-

Vertical shear injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. A vertically oriented fracture of the right superior pubic ramus is depicted with cranial displacement of the pubic symphysis and left hemipelvis.

-

Anteroposterior (AP) compression injury as seen on an AP radiograph of the pelvis. Characteristic features of an AP compression injury include symphyseal and sacroiliac joint diastasis. In this patient, the pubic symphysis and right sacroiliac joint are widened.

-

Windswept pelvis (lateral compression injury) as seen on a pelvic CT scan. The patient sustained a left lateral compression injury with internal rotation of the left hemipelvis and a characteristic sacral buckle fracture. Note the concomitant left sacroiliac joint diastasis. The lateral force vector continued across the pelvis to produce external rotation of the right hemipelvis and diastasis of the right sacroiliac joint. The combination of injuries resulted in a windswept pelvis.

-

Vertical shear injury as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. The left hemipelvis is displaced in a cranial direction with associated sacroiliac joint diastasis (long arrow). The vertically oriented fractures of the pubic rami usually are ipsilateral; however, in this patient, the rami fractures are contralateral (short arrow).

-

Lateral compression injury as seen on a pelvic CT scan. The left sacral buckle (anterior crush) fracture is more readily apparent on the CT scan than on other images.

-

Bilateral anterior inferior iliac spine avulsion fracture as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. Hyperextension of the hip occurred in this patient during a motor vehicle collision. The injury resulted in avulsion fractures at the origins of both rectus femoris muscles. Note that the integrity of the pelvic ring is preserved.

-

Iliac wing fracture as seen on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. A fracture of the left iliac wing occurred secondary to a direct blow to the left hemipelvis. The fracture does not involve the pelvic ring; therefore, the pelvis is stable.

-

Diastasis of the symphysis pubis, which most commonly indicates an anteroposterior compression injury.

-

The combination of a sacral buckle fracture and ipsilateral overlapping pubic rami fractures is characteristic of a lateral compression injury.

-

Avulsion fractures of the pelvis (eg, from the anterior inferior aspect of the iliac spine) do not affect the integrity of the pelvic ring. Isolated iliac wing fractures may occur as a result of a direct blow without disruption of the pelvic ring. With iliac crest, anterior iliac spine, and ischial tuberosity avulsion fractures, the integrity of the pelvic ring is also maintained.