Practice Essentials

Osteoid osteoma (OO) is a benign skeletal neoplasm of unknown etiology that is composed of osteoid and woven bone. It is typically found in children, adolescents, and young adults, with the age range being 10 to 35 years. Osteoid osteoma accounts for approximately 3% of all primary bone tumors and has a strong male predilection (male to female ratio, 3:1). [1] The tumor is usually smaller than 1.5 cm in diameter. Osteoid osteoma can occur in any bone, but in approximately two thirds of patients, the appendicular skeleton is involved. Although OO is rarely seen in the hand, one small series reported the following distribution of lesion locations: 67% in the proximal phalanx, 22% in the middle phalanx and 11% in the metacarpal. [2] The skull and facial bones are involved exceptionally. [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

Osteoid osteoma accounts for about 10% of all benign bone tumors and frequently affects the long bones of the femur and tibia. The size of the nidus is used to differentiate osteoid osteoma from osteoblastoma, with osteoblastomas typically being larger than 2 cm. [4]

Most patients with osteoid osteoma (demonstrated in the images below) are young. Rarely, an ossification center is affected. The classic presentation is that of focal bone pain at the site of the tumor. The pain worsens at night and increases with activity; it is dramatically relieved with small doses of aspirin. OO can present with a variety of neurologic symptoms, including muscle weakness and atrophy, diminished tendon reflexes, or gait disturbance, and these presentations are often associated with a delayed diagnosis. [8]

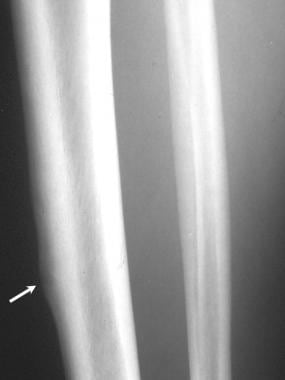

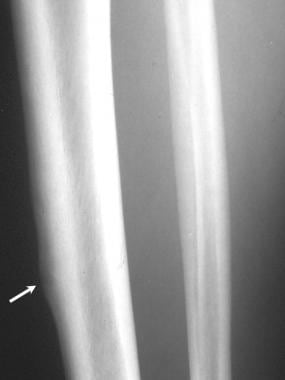

Plain radiograph in a 25-year-old man with cortical osteoid osteoma. Lateral view of the right tibia shows a radiolucent nidus surrounded by fusiform cortical thickening.

Plain radiograph in a 25-year-old man with cortical osteoid osteoma. Lateral view of the right tibia shows a radiolucent nidus surrounded by fusiform cortical thickening.

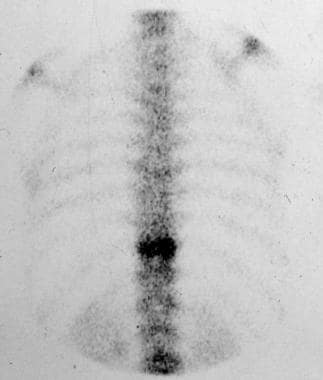

Radionuclide bone scan in a 25-year-old man with cortical osteoid osteoma (same patient as in the previous image) shows focal intense uptake of radioisotope corresponding to the site of radiographic abnormality, which is consistent with osteoid osteoma.

Radionuclide bone scan in a 25-year-old man with cortical osteoid osteoma (same patient as in the previous image) shows focal intense uptake of radioisotope corresponding to the site of radiographic abnormality, which is consistent with osteoid osteoma.

Transaxial CT scan in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain shows the sharply demarcated radiolucent nidus of the osteoid osteoma extending to the left pedicle.

Transaxial CT scan in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain shows the sharply demarcated radiolucent nidus of the osteoid osteoma extending to the left pedicle.

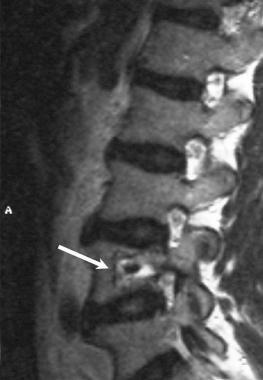

Sagittal T1-weighted MRI in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain. Osteoid osteoma of the L4 vertebral body was diagnosed. The nidus is hyperintense to the bone marrow but less intense than the fat. In this patient, MRI findings do not add to the CT findings.

Sagittal T1-weighted MRI in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain. Osteoid osteoma of the L4 vertebral body was diagnosed. The nidus is hyperintense to the bone marrow but less intense than the fat. In this patient, MRI findings do not add to the CT findings.

The lesion initially appears as a small sclerotic bone island within a circular lucent defect. This central nidus is seldom larger than 1.5 cm in diameter, and it may be associated with considerable overlying cortical and endosteal bone sclerosis. The tumors may regress spontaneously. The mechanism of this involution is not known, but tumor infarction is a possibility.

Shukla et al performed a retrospective review of radiographic, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans in 9 patients with osteoid osteoma of the foot and found that in young patients with chronic hindfoot pain and a normal radiograph, MRI features suggestive of possible osteoid osteoma included extensive bone marrow edema limited to a single bone, with a possible nidus demonstrated in two thirds of cases. The authors noted that the presence or absence of a nidus should be confirmed with high-resolution CT. [9]

In the Shukla study, classic symptoms (ie, night pain, relief with aspirin) were identified in 5 of 8 cases. In 5 patients, the lesion was located in the hindfoot (4 calcaneus, 1 talus), while 4 were in the midfoot or forefoot (2 metatarsal, 2 phalangeal). Radiographs were normal in all patients with hindfoot lesions, and CT identified the nidus in all cases except in a case of terminal phalanx lesion; MRI demonstrated a nidus in 6 of 9 cases.The nidus was of predominantly intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and of intermediate to high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. High-grade bone marrow edema limited to the affected bone and adjacent soft-tissue edema was identified in all cases. [9]

According to von Kalle et al, tailored high-resolution MRI with dynamic contrast enhancement can reliably diagnose osteoid osteomas and pinpoint the nidus. The authors retrospectively correlated the results of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI with histologic and clinical diagnoses in 54 patients with osteoid osteoma who were diagnosed by MRI. In 49 of 54 patients (90.7%), the diagnosis of osteoid osteoma was determined to be certain or highly probable, and 38 of 54 osteoid osteomas were histologically proven. Five MRI diagnoses were regarded as false positives. [10] The authors proposed a stepwise approach to the diagnosis of osteoid osteosarcoma, with short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences, dynamic contrast-enhanced scanning, and high-resolution, postcontrast T1 spin-echo sequences with fat saturation.

Preferred examination

Plain films may suggest the diagnosis, but in complex areas such as the spine, pelvis, wrist, and foot, additional imaging modalities are often required. On plain radiography and CT, a typical nidus surrounded by sclerosis or cortical thickening characterizes osteoid osteoma. MR is the imaging choice for most musculoskeletal disorders. SPECT/CT and PET/CT can help provide an accurate diagnosis and additional information for treatment planning. [5]

Radiography is the initial examination of choice and may be the only examination required. The nidus in spinal involvement may be difficult to detect by using plain radiographs. Intra-articular tumors are difficult to detect on plain radiographs because of the absent or limited sclerosis around the nidus.

CT is used for precise localization of the nidus and may be used for guiding percutaneous ablation. [11, 12, 13] CT has the disadvantage of ionizing radiation. MRI is a useful imaging technique, but CT appears superior for precise localization. On MRIs, tumors are not as conspicuous as they are on CT scans. [3, 5]

Angiography may be useful in differentiating the tumor from a Brodie abscess.

Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scanning is useful in the localization of the tumor when the spinal arch or spinous process is involved. [14, 15, 16, 17]

Radionuclide scanning for technetium-99m diphosphonate uptake shows fairly intense activity at the tumor site. This examination may also be used to localize the tumor preoperatively and to establish complete removal of the nidus by using a handheld radioactivity detector. Radionuclide scanning is a sensitive technique, and findings may be positive before radiographic changes are apparent. [18, 19] The specificity of radionuclide bone scanning is low.

Duplex color Doppler ultrasonography has been used to guide percutaneous localization and biopsy.

Ultrasonography has been used to aid in the diagnosis of intra-articular osteoid osteomas. Some have suggested that the sonographic findings of a cortical irregularity and focal synovitis indicate the possibility of intra-articular osteoid osteoma, prompting the search for characteristic findings on correlative imaging studies. [20, 21]

Radiography

Radiographs remain the mainstay of imaging in an orthopedic workup. Radiographic features of osteoid osteoma (seen in the images below) depend on the site of involvement, the duration of symptoms, and the age of the patient.Usually, radiography is the first examination performed in patients with bone pain. In three quarters of patients, a diagnosis may be suggested on the basis of the plain radiographic findings. However, some areas of the skeleton are difficult to assess by using plain radiographs in patients with a suspected osteoid osteoma. These areas include the spine, the femoral neck, and the small bones of the hands and feet. In the spine, overlapping shadows of the vertebral column can easily obscure the tumor.

Plain radiograph in a 25-year-old man with cortical osteoid osteoma. Lateral view of the right tibia shows a radiolucent nidus surrounded by fusiform cortical thickening.

Plain radiograph in a 25-year-old man with cortical osteoid osteoma. Lateral view of the right tibia shows a radiolucent nidus surrounded by fusiform cortical thickening.

Plain radiograph of the pelvis in a 6-year-old child who presented with left hip pain. The radiograph shows a well-defined area of sclerosis surrounded by a ring of radiolucency in the left femoral neck. Note the absence of periosteal reaction that suggests intramedullary or cancellous osteoid osteoma.

Plain radiograph of the pelvis in a 6-year-old child who presented with left hip pain. The radiograph shows a well-defined area of sclerosis surrounded by a ring of radiolucency in the left femoral neck. Note the absence of periosteal reaction that suggests intramedullary or cancellous osteoid osteoma.

Radiograph of the hip in an 8-year-old child who presented with left hip pain and restriction of movement. An intra-articular osteoid osteoma in the medial aspect of the femoral neck has resulted in periosteal new bone formation.

Radiograph of the hip in an 8-year-old child who presented with left hip pain and restriction of movement. An intra-articular osteoid osteoma in the medial aspect of the femoral neck has resulted in periosteal new bone formation.

Lateral view of the thoracic spine in a 56-year-old woman who presented with abdominal pain. Initial findings of chest radiography, intravenous pyelography, barium enema, and cholecystogram were normal. An isotope bone scan showed focal increased uptake in the vertebral body of the lower thoracic spine. Plain radiograph corresponding to the site of the abnormality shows a radiolucent lesion in the posterior aspect of the T11 vertebral body with surrounding sclerosis that was diagnosed as giant osteoid osteoma and later was confirmed at histologic analysis.

Lateral view of the thoracic spine in a 56-year-old woman who presented with abdominal pain. Initial findings of chest radiography, intravenous pyelography, barium enema, and cholecystogram were normal. An isotope bone scan showed focal increased uptake in the vertebral body of the lower thoracic spine. Plain radiograph corresponding to the site of the abnormality shows a radiolucent lesion in the posterior aspect of the T11 vertebral body with surrounding sclerosis that was diagnosed as giant osteoid osteoma and later was confirmed at histologic analysis.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the lumbar spine in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain. Radiograph shows a well-defined sclerotic lesion in the left side of the L4 vertebral body.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the lumbar spine in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain. Radiograph shows a well-defined sclerotic lesion in the left side of the L4 vertebral body.

Lateral view of the lumbar spine in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain. The radiolucent nidus is seen clearly; a central area of sclerosis consistent with osteoid osteoma is visible.

Lateral view of the lumbar spine in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain. The radiolucent nidus is seen clearly; a central area of sclerosis consistent with osteoid osteoma is visible.

A circular or ovoid lucent defect is seen in 75% of patients. This defect is usually smaller than 1.5 cm in diameter and is associated with a variable degree of cortical and endosteal sclerosis.

The site of the tumor determines the degree of bone sclerosis. In medullary tumors, sclerosis is minimal or absent. Cortical and subperiosteal tumors provoke considerable sclerosis. Long-standing tumors demonstrate more sclerosis. Children also mount more of a sclerotic response than do adults.

In subarticular and intracapsular tumors, reactive sclerosis may be absent or minimal, or it may occur relatively distant to the lesion. This sclerosis usually occurs in tumors of the femoral neck, because no periosteum covered by articular cartilage is present on the surface. However, whatever periosteum exists beyond the areas covered by the articular cartilage cannot be elevated because it is bound down by enhancing Sharpey fibers.

Intra-articular tumors may show joint effusion associated with the premature loss of cartilage. Osteoarthrosis affects approximately one half of patients with intra-articular tumors. Rarely, patients experience regional osteoporosis, presumably as a result of disuse. Regional osteoporosis may appear as an area of osteopenia around a joint.

With spinal involvement, alignment abnormalities may be obvious, such as scoliosis, kyphosis, or hyperlordosis. In children with a long-standing tumor, the involved bone may demonstrate overgrowth.

Supplementary radiographic methods, such as overpenetrated radiographs or thin-section planning radiographs, may be useful in locating tumors in portions of the skeleton with complex anatomy.

A long list of conditions may mimic an osteoid osteoma. If excessive, new bone formation can mask the nidus, resulting in a false-negative diagnosis. When the tumor is in a long bone, a periosteal reaction may occur distant to the lesion or in an adjacent bone; these may cause diagnostic problems. However, this difficulty should not deter the radiologist from making the diagnosis.

Particular pitfalls include a Brodie abscess and a tumor in the long bones of children where overgrowth may occur. Osteoblastoma and osteoid osteoma have a propensity for the posterior elements of the spine. Both are osteoblastic tumors; they are differentiated primarily by their sizes. Osteoblastomas become considerably larger than osteoid osteomas and are better depicted on plain radiographs.

Computed Tomography

CT scanning is the ultimate diagnostic tool for the precise localization of the nidus. The nidus enhances after the intravenous administration of contrast medium. The nidus shows a variable degree of mineralization, which may be amorphous, punctate, ringlike, or, in rare cases, uniformly dense. Reactive sclerosis around the nidus varies from being extremely dense to manifesting no reaction at all. The CT scan features of osteoid osteoma are demonstrated in the images below.

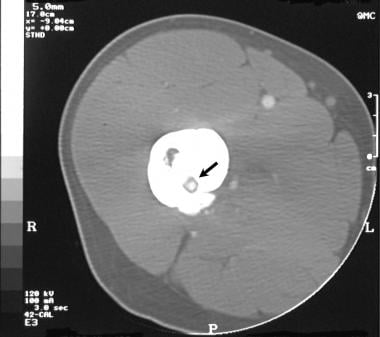

Transaxial CT scan through the proximal shaft of the right femur in a 17-year-old boy. The scan localizes the osteoid osteoma adjacent to the endosteal margin of the cortex. Note a central sclerotic focus in the radiolucent nidus, which is characteristic of osteoid osteoma.

Transaxial CT scan through the proximal shaft of the right femur in a 17-year-old boy. The scan localizes the osteoid osteoma adjacent to the endosteal margin of the cortex. Note a central sclerotic focus in the radiolucent nidus, which is characteristic of osteoid osteoma.

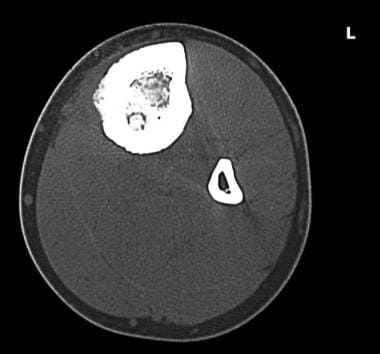

Transaxial CT scan in a 20-year-old man with osteoid osteoma obtained through the mid shaft of the left tibia reveals a radiolucent nidus with a central area of sclerosis. Note the adjacent endosteal and cortical thickening.

Transaxial CT scan in a 20-year-old man with osteoid osteoma obtained through the mid shaft of the left tibia reveals a radiolucent nidus with a central area of sclerosis. Note the adjacent endosteal and cortical thickening.

Transaxial CT scan in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain shows the sharply demarcated radiolucent nidus of the osteoid osteoma extending to the left pedicle.

Transaxial CT scan in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain shows the sharply demarcated radiolucent nidus of the osteoid osteoma extending to the left pedicle.

Interventional radiology is now considered first-line treatment for osteoid osteoma either as needle-guided radiofrequency ablation or needleless technique (magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound surgery). [3] Under CT guidance, the tumor can be percutaneously ablated by using radiofrequency, ethanol, laser, or thermocoagulation therapy. In spinal tumors, complete ablation or resection of the tumor is desirable but not always feasible. Percutaneous RF ablation is performed under CT guidance by using general or spinal anesthesia. After localization of the nidus with 1- to 3-mm CT sections, an osseous access is established with either a 2-mm coaxial drill system or an 11-gauge Jamshidi needle. [22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 6, 7]

In a study by Chahal et al of 87 patients with appendicular osteoid osteoma who underwent CT-guided radiofrequency ablation, the primary success rate after a single session was 86.2%(75/87 patients), and overall success rate after one/two sessions was 96.6%(84/87). [6]

Nijland et al studied the treatment results of osteoid osteoma in 86 patients and found that CT-guided radiofrequency ablation had a clinical success rate of 81.4%, with complete ablation achieved in 79% of procedures. [7]

Degree of confidence

CT is the ultimate tool for the detection and the precise localization of the nidus. It is particularly effective in areas with complex anatomy, such as the spinal pedicles, laminae, and femoral neck.

Excellent long-term results have been reported following CT-guided radiofrequency ablation of osteoid osteomas. There is no correlation of the CT and MRI patterns with the clinical outcome. Rehnitz et al suggested that treatment decisions not be based solely on the imaging findings and that investigators be familiar with the variety of imaging patterns after radiofrequency ablation. [31]

As a result of the partial volume effect in small lesions, problems can occur with CT scanning. Rarely, osteoid osteoma may be confused with a Brodie abscess. False-negative CT results may occur with extracortical tumors. CT scans may not help in diagnosing osteoid osteoma when the nidus is in a cancellous location because of a lack of changes in attenuation around the nidus.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI reliably demonstrates the nidus, which has a variable appearance related to its position relative to the cortex of the bone. Compared with other techniques, MRI is better in the diagnosis of cancellous osteoid osteomas, whereas difficulty may be encountered by using plain radiography and CT. The nidus is isoechoic to muscle on T1-weighted MRI. The signal intensity increases with T2-weighted sequences, but it remains low. Bone marrow edema is depicted around the nidus in approximately 60% of patients. Soft tissue edema is depicted adjacent to the tumor in slightly fewer than one half of patients. Perinidal edema is more pronounced in young patients. Intra-articular lesions cause synovial thickening or inflammation and joint effusion, which may be readily apparent on MRIs. [15, 17, 32]

(See the images below.)

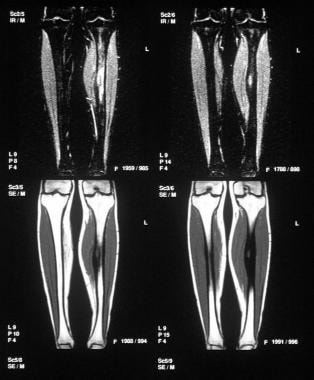

Coronal short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) and T1-weighted MRIs in a 20-year-old man with osteoid osteoma. The nidus is isointense to the muscle on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on the STIR images. Note the perinidal marrow edema, which is depicted better with the STIR sequence.

Coronal short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) and T1-weighted MRIs in a 20-year-old man with osteoid osteoma. The nidus is isointense to the muscle on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on the STIR images. Note the perinidal marrow edema, which is depicted better with the STIR sequence.

Sagittal T1-weighted MRI in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain. Osteoid osteoma of the L4 vertebral body was diagnosed. The nidus is hyperintense to the bone marrow but less intense than the fat. In this patient, MRI findings do not add to the CT findings.

Sagittal T1-weighted MRI in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain. Osteoid osteoma of the L4 vertebral body was diagnosed. The nidus is hyperintense to the bone marrow but less intense than the fat. In this patient, MRI findings do not add to the CT findings.

Sagittal T2-weighted MRI in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain shows increased signal intensity in the nidus. The central area of sclerosis shows low signal intensity on both images.

Sagittal T2-weighted MRI in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain shows increased signal intensity in the nidus. The central area of sclerosis shows low signal intensity on both images.

MRI is not as effective in the diagnosis of intracortical tumors as it is in the diagnosis of cancellous bone tumors. Differences in MR perfusion parameters have been reported in patients who have had successful treatment and those patients with recurrent osteoid osteoma. Teixeira et al identified an early and steep enhancement with short time to peak and a short delay between the arterial and nidus peaks on MR perfusion in the postoperative setting as highly indicative of an osteoid osteoma recurrence. [33]

Nuclear Imaging

Radionuclide bone scanning of uptake of technetium-99m phosphonates shows intense activity at the site of the tumor. Occasionally, a double-density sign is seen in which a small focus of radioactivity in the nidus is superimposed on a larger area of radioactivity. (The radionuclide scan features of osteoid osteoma are seen in the images below.) [14, 16]

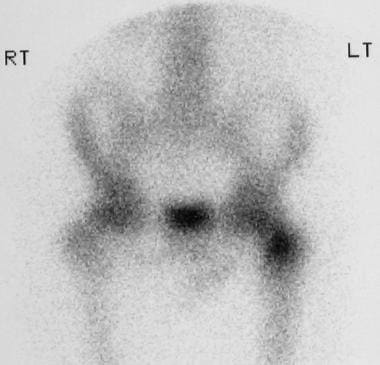

Radioisotope bone scan in a 6-year-old child who presented with left hip pain demonstrates intense uptake in the left proximal femur.

Radioisotope bone scan in a 6-year-old child who presented with left hip pain demonstrates intense uptake in the left proximal femur.

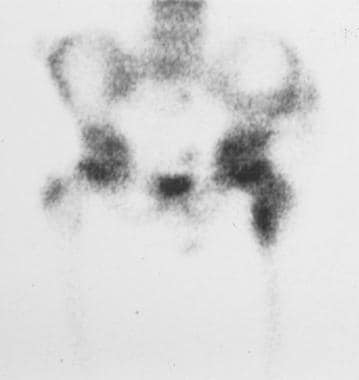

Radionuclide bone scan of the hip in an 8-year-old child who presented with left hip pain and restriction of movement shows avid uptake in the left femoral neck, which is consistent with osteoid osteoma.

Radionuclide bone scan of the hip in an 8-year-old child who presented with left hip pain and restriction of movement shows avid uptake in the left femoral neck, which is consistent with osteoid osteoma.

Radioisotope scan of the thoracic spine in a 56-year-old woman with giant osteoid osteoma who presented with abdominal pain shows increased uptake in the T11 vertebral body.

Radioisotope scan of the thoracic spine in a 56-year-old woman with giant osteoid osteoma who presented with abdominal pain shows increased uptake in the T11 vertebral body.

SPECT scanning may be useful in areas with complex anatomy, such as the posterior elements of the spine. Radionuclide imaging may be used preoperatively and intraoperatively as well, to localize the tumor and to establish complete removal of the nidus by using a handheld radioactivity detector.

Positron-emission tomography (PET) scanning with 18-fluorodeoxyglucose has also been used in the diagnosis of osteoid osteoma. [34]

Degree of confidence

The average time from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis is reported to be 28 months with spinal tumors. Radionuclide bone scanning has been found to reduce the time to diagnosis in 66% of patients. The sensitivity of radionuclide bone scans is extremely high. A radionuclide bone scan is considered mandatory in patients with painful scoliosis. A radionuclide bone scan can demonstrate the tumor before abnormal radiographic findings are apparent.

No false-negative results have been recorded in osteoid osteoma. However, the specificity of isotope bone scans does not match its sensitivity, and a variety of infective, neoplastic, metabolic, and traumatic lesions show increased activity.

Angiography

An osteoid osteoma is highly vascular, which is a feature that can be demonstrated angiographically. The nidus is the most vascular part of the tumor, with an intense circumscribed blush that appears in the early arterial phase and that persists into the venous phase.

Blush persisting into the venous phase during angiography is believed to be diagnostic of osteoid osteoma.

A Brodie abscess may be difficult to distinguish from osteoid osteoma radiologically. Hypervascularity may also be observed with a Brodie abscess, but the characteristic blush seen in the venous phase in osteoid osteoma usually does not occur in a Brodie abscess.

-

Plain radiograph in a 25-year-old man with cortical osteoid osteoma. Lateral view of the right tibia shows a radiolucent nidus surrounded by fusiform cortical thickening.

-

Radionuclide bone scan in a 25-year-old man with cortical osteoid osteoma (same patient as in the previous image) shows focal intense uptake of radioisotope corresponding to the site of radiographic abnormality, which is consistent with osteoid osteoma.

-

Transaxial CT scan through the proximal shaft of the right femur in a 17-year-old boy. The scan localizes the osteoid osteoma adjacent to the endosteal margin of the cortex. Note a central sclerotic focus in the radiolucent nidus, which is characteristic of osteoid osteoma.

-

Nonenhanced and intravenous gadolinium-enhanced axial T1-weighted MRIs in a 17-year-old boy with osteoid osteoma. The images demonstrate the nidus, with a central low-signal-intensity dot corresponding to the sclerotic area on the previous image, a CT scan. Note the enhancement of perilesional soft tissue edema.

-

Transaxial CT scan in a 20-year-old man with osteoid osteoma obtained through the mid shaft of the left tibia reveals a radiolucent nidus with a central area of sclerosis. Note the adjacent endosteal and cortical thickening.

-

Coronal short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) and T1-weighted MRIs in a 20-year-old man with osteoid osteoma. The nidus is isointense to the muscle on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on the STIR images. Note the perinidal marrow edema, which is depicted better with the STIR sequence.

-

Plain radiograph of the pelvis in a 6-year-old child who presented with left hip pain. The radiograph shows a well-defined area of sclerosis surrounded by a ring of radiolucency in the left femoral neck. Note the absence of periosteal reaction that suggests intramedullary or cancellous osteoid osteoma.

-

Radioisotope bone scan in a 6-year-old child who presented with left hip pain demonstrates intense uptake in the left proximal femur.

-

Radiograph of the hip in an 8-year-old child who presented with left hip pain and restriction of movement. An intra-articular osteoid osteoma in the medial aspect of the femoral neck has resulted in periosteal new bone formation.

-

Radionuclide bone scan of the hip in an 8-year-old child who presented with left hip pain and restriction of movement shows avid uptake in the left femoral neck, which is consistent with osteoid osteoma.

-

Radiograph of the right great toe in a 24-year-old woman shows a partly calcified lesion in the medulla of the distal phalanx, with no periosteal new bone formation suggestive of osteoid osteoma.

-

Radioisotope bone scan of the right great toe in a 24-year-old woman demonstrates focal intense uptake at the site corresponding to the abnormal findings found in the previous image, a radiograph.

-

Lateral view of the thoracic spine in a 56-year-old woman who presented with abdominal pain. Initial findings of chest radiography, intravenous pyelography, barium enema, and cholecystogram were normal. An isotope bone scan showed focal increased uptake in the vertebral body of the lower thoracic spine. Plain radiograph corresponding to the site of the abnormality shows a radiolucent lesion in the posterior aspect of the T11 vertebral body with surrounding sclerosis that was diagnosed as giant osteoid osteoma and later was confirmed at histologic analysis.

-

Radioisotope scan of the thoracic spine in a 56-year-old woman with giant osteoid osteoma who presented with abdominal pain shows increased uptake in the T11 vertebral body.

-

Anteroposterior radiograph of the lumbar spine in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain. Radiograph shows a well-defined sclerotic lesion in the left side of the L4 vertebral body.

-

Lateral view of the lumbar spine in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain. The radiolucent nidus is seen clearly; a central area of sclerosis consistent with osteoid osteoma is visible.

-

Transaxial CT scan in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain shows the sharply demarcated radiolucent nidus of the osteoid osteoma extending to the left pedicle.

-

Sagittal T1-weighted MRI in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain. Osteoid osteoma of the L4 vertebral body was diagnosed. The nidus is hyperintense to the bone marrow but less intense than the fat. In this patient, MRI findings do not add to the CT findings.

-

Sagittal T2-weighted MRI in a 52-year-old man who had a biopsy-proven giant osteoid osteoma (osteoblastoma) and who presented with severe low back pain shows increased signal intensity in the nidus. The central area of sclerosis shows low signal intensity on both images.