Practice Essentials

Trochanteric bursitis is characterized by painful inflammation of the bursa located just superficial to the greater trochanter of the femur. [1, 2, 3, 4] Activities involving running and those involving the possibility of falls or physical contact, as well as lateral hip surgery and certain preexisting conditions, are potentially associated with trochanteric bursitis.

Patients typically complain of lateral hip pain, though the hip joint itself is not involved. The pain may radiate down the lateral aspect of the thigh. [5]

Symptoms of trochanteric bursitis

The classic symptom of trochanteric bursitis is pain at the greater trochanteric region of the lateral hip. The pain may radiate down the lateral aspect of the ipsilateral thigh; [5] however, it should not radiate all the way into the foot. Onset may be either insidious or acute. The symptoms are made worse when the patient lies on the affected bursa (that is, when lying in the lateral decubitus position).

Hip movements (internal and external rotation), walking, running, weight-bearing, and other strenuous activities can exacerbate the symptoms. Patients may report that the pain limits their strength and makes their legs feel weak.

Diagnosis of trochanteric bursitis

The most classic physical finding in trochanteric bursitis, also known as greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS), is point tenderness over the greater trochanter, which reproduces the presenting symptoms. Palpation may also reproduce pain that radiates down the lateral thigh. Additionally, it has been reported that tenderness to areas that are either superior or posterolateral to the trochanter can be identified. [6]

Lateral hip pain can often be elicited by carrying out passive external rotation of the hip without provoking such symptoms by internal rotation or performing end-range adduction. [7] In addition, the external rotation can be combined with passive hip abduction. Lateral hip pain can be reproduced with flexion of the hip followed by resisted hip abduction. Groin pain or referred knee pain provoked by passive internal rotation of the hip may indicate hip joint pathology (eg, osteoarthritis). Performing other specific musculoskeletal examinations, such as the Trendelenberg test and Ober test, can help to identify other structural derangements that may lead to lateral hip pain. [7, 8]

Plain radiography of the hip and femur may be performed to assess for possible fracture, underlying degenerative arthritis, or bony lesions, or for inflammation-related calcium deposition in the region of the greater trochanteric bursa (which may be associated with chronic trochanteric bursitis).

Bone scanning, computed tomography (CT) scanning, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to exclude underlying diseases.

Management of trochanteric bursitis

Treatment of trochanteric bursitis may include relative rest, application of ice, injection of corticosteroids and local anesthetics, administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and application of topical, sustained-release local anesthetic patches. [9, 10] Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) is a good alternative to traditional nonoperative therapy.

A physical therapist can instruct the patient in a home exercise program, emphasizing stretching of the iliotibial band (ITB), the tensor fascia lata (TFL), the external hip rotators, the quadriceps, and the hip flexors. The use of phonophoresis and soft-tissue massage also may be helpful. [11]

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) can be considered in cases that prove resistant to the rehabilitation program, and surgical interventions can be useful in refractory cases. [11] When surgery is warranted, longitudinal release of the ITB combined with subgluteal bursectomy appears to be safe and effective for most patients. [12]

Pathophysiology

Acute or repetitive (cumulative) trauma may give rise to inflammation of the affected bursa. Acute trauma includes contusions from falls, contact sports, and other sources of impact.

Other factors that may predispose to trochanteric bursitis include a leg-length discrepancy and lateral hip surgery. [13] Even if no true anatomic leg-length discrepancy is present, running on banked surfaces essentially produces a functional leg-length discrepancy because the contact surface of the downhill foot is lower. In addition, individuals with a broader greater trochanteric width in relation to their iliac crest width appear to be more likely to develop trochanteric bursitis. [14]

A retrospective case-control study by Canetti et al found that in cohort patients with surgical-stage greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS [see the next paragraph]), the mean sacral slope was significantly lower than that in asymptomatic hip patients (33.1° vs 39.6°, respectively). [15]

The term greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS) is now frequently substituted for the term trochanteric bursitis. Ongoing research using ultrasonography, MRI, and histologic analysis suggests that GTPS may be a better label for this condition, in that the regional pain and reproducible tenderness may be associated with myriad causes besides bursitis, such as tendinitis, tendinosis, tendinopathy, muscle tears, trigger points, ITB disorders, and general or localized pathology in surrounding tissues. [2, 16, 17, 18]

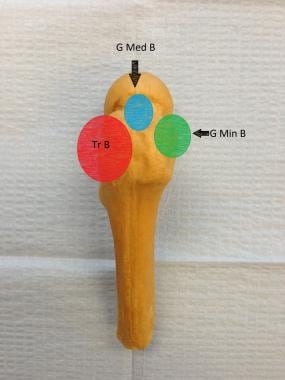

It is also worth noting that there are several other bursae in the vicinity of the trochanteric bursa (as noted in the image below) that may also present with pain. The subgluteus medius bursa lies between the gluteus medius tendon and the anterior-superior aspect of the lateral greater trochanter. The subgluteus minimus bursa lies between the gluteus medius tendon and the anterior facet of the greater trochanter. In addition, the subgluteus maximus bursa is more distally located between the distal attachment of the gluteus maximus and the femur. [19] Despite this, the older term, trochanteric bursitis, is still commonly used to describe most lateral hip pain.

Etiology

Acute trauma (eg, from a fall or tackle) that causes the patient to land on the lateral hip region can result in trochanteric bursitis. More commonly, repetitive (cumulative) trauma is involved. Such trauma is caused by the repetitive contracture of the gluteus medius, the ITB, or both during running or walking.

Conditions that predispose patients to trochanteric bursitis include underlying lower leg gait disturbances, spinal disorders, and sacroiliac disturbances. Osteoarthritis of the hip may also be responsible, though this diagnosis generally manifests as groin or knee pain rather than lateral hip pain. Another predisposing factor is piriformis syndrome, because the piriformis muscle inserts on the greater trochanter.

Trochanteric bursitis can also develop as a complication of arthroscopic surgery of the hip (in an estimated 1.4% of cases). [20, 21, 22] At times, the bursitis develops spontaneously, without apparent precipitating factors.

A study by Fearon et al suggested that the pain of GTPS may be associated with an increased expression of substance P in the trochanteric bursa. The investigators found the presence of substance P in the trochanteric bursa to be significantly greater in patients with GTPS than in the controls, although the neuropeptide’s presence in tendons attaching to the greater trochanter did not differ significantly between the two groups. [23]

A study by Vap et al found a 7% prevalence of chronic trochanteric bursitis in patients with femoroacetabular impingement (FAI). The likelihood of chronic trochanteric bursitis in this group was 5.3 times greater in females than in males and 2.5 times greater in patients over age 30 years. [24]

Epidemiology

Trochanteric bursitis (ie, GTPS) is relatively common among physically active and sedentary patients. The prevalence of unilateral GTPS is 15.0% in women and 8.5% in men, and that of bilateral GTPS is 6.6% in women and 1.9% in men. [25] In a study by Lievense et al, the annual incidence of trochanteric pain in primary care was reported as being 1.8 per 1000 patients. [26]

Trochanteric bursitis can occur in adults of any age. Lievense et al found that trochanteric bursitis appeared to be much more common in females (80%) than in males. [26] No racial predilection has been reported.

Prognosis

No mortality is associated with trochanteric bursitis. Morbidity includes chronic pain, limping, and pain-related sleep disturbances that occur when the patient is lying on the affected side. [27]

A prospective study by Dzidzishvili et al indicated that in trochanteric bursitis, the likelihood of poor clinical outcomes appears to be increased by obesity, smoking, emotional stress, fibromyalgia and hypothyroidism. In contrast, better overall physical function was found to be associated with the use of fewer corticosteroid infiltrations, a shorter length of time between symptom onset and surgery, being a nonsmoker, and the absence of prior lumbosacral fusion. [28]

Most patients with trochanteric bursitis respond very well to a combination of corticosteroid injection, physical therapy, and activity restriction. Some patients may require repetition of the corticosteroid injection.

A retrospective study of 164 patients who presented with trochanteric pain found that at least 36% were still symptomatic after 1 year and 29% were still symptomatic after 5 years; thus, many patients developed chronic pain at this site. [26] Patients with osteoarthritis (OA) in the lower limbs had a 4.8-fold greater risk of persistent symptoms after 1 year than patients without OA. Patients treated with corticosteroid injection were 2.7 times less likely to have chronic pain at this site at 5 years than patients who were not treated in this manner.

A study by Robertson-Waters et al indicated that GTPS occurring after total hip arthroplasty is less responsive to surgery than is idiopathic GTPS, with postoperative satisfaction, Oxford Hip Scores, and visual analogue scale scores having been better for study patients in the idiopathic group. [29]

Patient Education

As with any medical condition, patients should be educated with regard to the nature of the condition, causative factors, and treatment plan. As with any therapy involving injection, patients should be educated to watch for any signs or symptoms of local infection at the injection site.

As with any corticosteroid injection, diabetic patients should be instructed that they may experience a transient increase in their blood glucose levels. All patients should be informed that symptoms usually do not begin to improve until a few days after the corticosteroid injection. Patients should also understand that they may experience a mild, transient increase in symptoms during the window of time during which the local anesthetic has worn off but the corticosteroids have not yet begun to have a therapeutic effect.

-

Tr B = trochanteric bursa; G Med B = subgluteus medius bursa; G Min B = subgluteus minimus bursa.

-

Photo demonstrates method of stretching iliotibial band (ITB) in standing position. One foot is crossed over other, and patient leans away from side being stretched. Exercise is performed by allowing side that will be stretched to lean in toward wall. Patient should feel stretch at lateral aspect of hip that is closest to wall. Stretching should be done in controlled, sustained manner, never a ballistic manner with sudden jerking movements.

-

Photo demonstrates method of stretching iliotibial band (ITB) in supine position. Foot ipsilateral to stretch is crossed over contralateral knee. Next, thigh ipsilateral to stretch is pulled across midline (adduction). Patient should feel stretch at lateral aspect of hip, in area shown by dark line. Stretching should be done in controlled, sustained manner, never in ballistic manner with sudden jerking movements.