Practice Essentials

Advances in the medical and surgical treatments of intestinal failure have led to a decrease in the number of transplants over the past decade. Patient survival has improved and morbidity associated with parenteral nutrition, including liver failure, has declined. Nevertheless, intestine transplant still plays an important role in the treatment of intestinal failure. [1] Short gut syndrome (SGS)—congenital and non-congenital—and functional gastrointestinal pathologies (eg, pseudo-obstruction) are the most common causes leading to an intestine or intestine-liver transplant. [2]

Intestine transplantation may be performed in isolation, with liver transplant, or as part of a multi-visceral transplant including any combination of liver, stomach, pancreas, and/or colon. There are notable differences in patient and transplant outcomes for intestine transplants with and without liver. [1]

Background

As with the transplantation of other organs, the history of intestinal transplantation begins with Carrel and his description of a method of performing vascular anastomosis. [3, 4] In 1959, the first canine model of intestinal transplantation was reported by Lillihei and coworkers at the University of Minnesota. [5] The first intestinal transplant in humans was performed by Deterling in Boston in 1964 (unpublished data). The first reported human intestinal transplant was performed by Lillihei and coworkers in 19677. Before 1970, eight clinical cases of small-intestine transplantation were reportedly performed worldwide; maximum graft survival time was 79 days, and all patients died of technical complications, sepsis, or rejection.

In 1988 Deltz and coworkers in Kiel, Germany, performed what is considered to be the first successful intestinal transplant. [6] Soon after, other successful outcomes were reported by the groups headed by Goulet and coworkers in Paris [7] and Grant and coworkers in London, Canada, who had established the first intestinal transplant programs. [8, 9] A total of 15 isolated small-intestine transplantations were performed from 1985-1990 using cyclosporine.

Waitlist and Patient Profile

As of February 2021, the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (OPTN) listed 214 patients awaiting intestinal transplantation. [10] At the end of 2019, 20.6% of candidates had been on the waiting list for less than 1 year, 15.4% for 1 to less than 2 years, 28.6% for 2 to less than 5 years, and 35.3% for 5 or more years. [1] Among candidates listed in 2018‐2019, median time to transplant was 9.7 months for intestine candidates and 6.2 months for intestine‐liver candidates. [1]

In 2019, 30.9% of patients on the intestine transplant waiting list were in medical urgency status 1 (ie, at risk of imminent death); 52.2% of patients awaiting intestine-liver transplant were in status 1. The pretransplant mortality rate on the waiting list in 2019 was higher 15.5 deaths per 100 waitlist‐years for adult candidates and 3.1 deaths per 100 waitlist‐years for pediatric candidates. Pretransplant mortality was higher for intestine‐liver candidates than for intestine transplant candidates (13.0 versus 2.9 deaths per 100 waitlist years, respectively). [1]

Non-congenital short gut syndrome (SGS) was the most common reason for transplantation in 2019, accounting for 48.8% of intestine transplants and 30.0% of intestine-liver transplants. Other etiologies included necrotizing enterocolitis, congenital SGS, pseudo-obstruction, and enteropathies. [1]

In 2019, a total of 81 intestine transplants were performed in the United States, 41 intestine without liver and 40 intestine-liver.Over the past decade, the age distribution of candidates in the waitlist for intestine and intestine-liver transplant shifted from primarily pediatric to increasing proportions of adults. Adults accounted for 41% of candidates on the list at any time during the year, with a stable proportion of those aged 18-34 years and a decrease in those aged 35 years or older. In 2012‐2014, the 1‐ and 5‐year graft survival for intestine transplants with or without a liver was 81.1% and 60.8%, respectively, for recipients aged younger than 18 years and 68.9% and 44.7% for recipients aged 18 years or older. [1]

Problem

Intestinal failure is characterized by the inability to maintain protein energy, fluid, electrolyte, or micronutrient balance due to GI disease when on a normal diet. Intestinal failure ultimately leads to malnutrition and even death if the patient does not receive parenteral nutrition or receives an intestinal transplant.

In the United States in 2019, necrotizing enterocolitis and pseudo-obstruction were more common among candidates listed for intestine transplant, while non-congenital short gut syndrome (SGS) and enteropathies were more common among intestine-liver candidates. Congenital SGS was about equally common in intestine and intestine-liver candidates. [1] Worldwide, the leading cause of intestinal failure is SGS (68%) followed by functional bowel patholgies (15%). [11]

In children, the following are the main causes of intestinal failure:

-

Gastroschisis

-

Microvillus involution disease

-

Midgut volvulus

-

Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction

-

Massive resections secondary to tumor or other pathologies

The following are the leading causes of intestinal failure in adults:

-

Crohn disease

-

Massive small bowel infarct due to superior mesenteric artery and/or vein thrombosis

-

Trauma

-

Desmoid tumor including the root of the mesentery

-

Volvulus

-

Pseudo-obstruction

-

Multiple gastrointestinal resections for surgical complications

-

Radiation enteritis

Parenteral nutrition is the current standard of care for patients with intestinal failure. Nevertheless, the long-term use of parenteral nutrition is often associated with potentially life-threatening complications, including the following [12] :

-

Catheter-related sepsis

-

Catheter-related thrombosis

-

Severe dehydration

-

Metabolic derangements

-

Loss of sites for vascular access

-

Intestinal failure–associated liver disease (IFALD)

IFALD is partly caused by omega-6 fatty acids in parenteral nutrition formulas, which can be synthesized into inflammatory molecules. IFALD can range from steatohepatitis, cholestasis, or hepatic fibrosis to end-stage liver disease. Children are more likely to have cholestatic liver disease than steatohepatitis. [13] Severe liver injury has been reported in as many as 50% of patients with intestinal failure who receive parenteral nutrition for longer than 5 years; this is typically fatal. If patients have life-threatening infections, IFALD, or lose their venous access, 1 year mortality is 70% without intestinal transplantation. [14] .

As an early alternative to transplantation or total parenteral nutrition (TPN) for patients with short bowel syndrome, surgical bowel lengthening without transplant may be attempted. This requires the serial transverse enteroplasty (STEP) or longitudinal intestinal lengthening and tailoring (LILT) procedures. [15, 16]

STEP and LILT are particularly successful in patients with decreased transit times and dilated bowel. If successful, it may reduce the amount of TPN required, or obviate its use altogether. In one study of 22 children who underwent STEP and/or LILT, 50% were weaned off parenteral nutrition and there were no surgical complications or deaths. [17]

Indications

Intestinal transplantation should be recommended for patients on TPN with associated problems listed below:

-

Impending or overt liver failure secondary to IFALD

-

Thrombosis of two or more central veins

-

Two or more episodes per year of systemic sepsis secondary to line infections, or a single episode of fungal sepsis [18]

-

Frequent episodes of severe dehydration

Additional indications for intestinal transplantation include the following:

-

Severe short bowel syndrome (gastrostomy, duodenostomy, residual small bowel [< 10 cm in infants, < 20 cm in adults])

-

Intestinal failure with frequent hospitalizations, narcotic dependency, or pseudoobstruction

-

Patient unwillingness or inability to resume long-term parenteral nutrition

-

In highly selected patients, multivisceral organ transplantation may have a role in the treatment of slow-growing abdominal cancers that are deemed non-resectable [19]

Relevant Anatomy

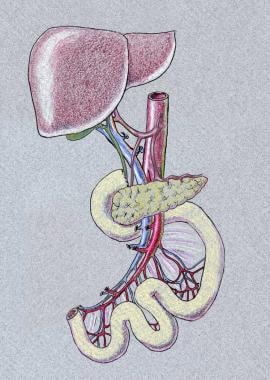

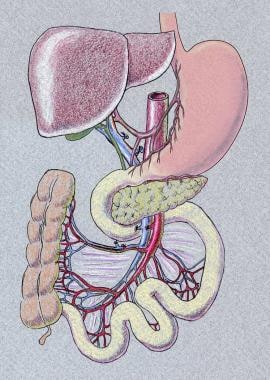

Isolated intestinal transplant entails ileum and jejunum transplantation. Liver-intestine transplant entails transplantation of liver, pancreas, duodenum, and intestine en bloc. When recipient foregut is preserved, a portocaval shunt needs to be performed. Another version is multivisceral transplantation, which also includes the stomach in addition to liver, pancreas, and intestine. The need for colon graft varies, depending on the patient's underlying disease and anatomy.

Below are images representing liver-bowel and multivisceral transplantation.

Vascular inflow and outflow varies by graft type. Isolated intestine graft is procured with the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and these are anastomosed to either the recipient's SMA and SMV or to the aorta and vena cava. If vascular conduit is necessary, donor iliac vesels or carotid artery can be used. If liver-intestine or multivisceral transplantation is performed, graft inflow would be donor abdominal aorta, and donor thoracic aorta is used for extension. Suprahepatic vena cava would serve as outflow.

Contraindications

The contraindications to intestinal transplantation are essentially the same as those in other types of transplants. Examples include the following:

-

Severe cardiopulmonary conditions (eg, severe pulmonary hypertension, advanced cardiac failure) precluding major operation

-

Active or uncontrolled infection or active malignancy

-

Psychosocial factors (ie, the lack of capability to assume the responsibilities of the day-to-day management following the transplant or the absence of social support)

-

Isolated small bowel graft.

-

Liver-small bowel graft, including the pancreas.

-

Multivisceral graft, including stomach-liver-pancreas-small bowel and right colon.

-

Isolated intestinal transplant. A gastrostomy tube, jejunostomy tube, and loop ileostomy are in place.