Practice Essentials

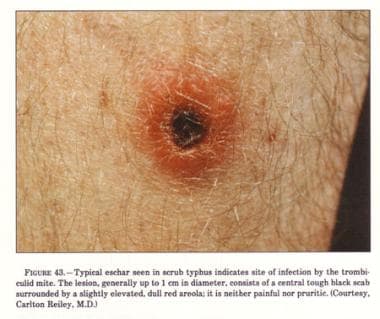

Scrub typhus is an acute, febrile, infectious illness that is caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi. The name derives from the type of vegetation (ie, terrain between woods and clearings) that harbors the vector. The image below depicts a typical eschar seen in scrub typhus.

Signs and symptoms

Elements brought out in the history may include the following:

-

Travel to an area where scrub typhus is endemic

-

Chigger bite (often painless and unnoticed)

-

Incubation period of 6-20 days (average, 10 days)

-

Headaches, shaking chills, lymphadenopathy, conjunctival injection, fever, anorexia, and general apathy

-

Rash; a small, painless, gradually enlarging papule, which leads to an area of central necrosis and is followed by eschar formation

Although many other conditions can present with a high fever, the presentation of the rash, a history of exposure to endemic areas, and the presentation of the sore caused by the bite can be diagnostic of scrub fever.

Physical findings may include the following:

-

Site of infection marked by a chigger bite

-

Eschar at the inoculation site (in about 50% of patients with primary infection and 30% of those with recurrent infection)

-

High fever (40-40.5°C [104-105°F]), occurring more than 98% of the time

-

Tender regional or generalized lymphadenopathy, occurring in 40-97% of cases

-

Less frequently, ocular pain, wet cough, malaise, and injected conjunctiva

-

Centrifugal macular rash on the trunk

-

Enlargement of the spleen, cough, and delirium

-

Pneumonitis or encephalitis

-

Central nervous system (CNS), pulmonary, or cardiac involvement

-

Rarely, acute renal failure, shock, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies in patients with scrub typhus may reveal the following:

-

Early lymphopenia with late lymphocytosis

-

Decreased CD4:CD8 lymphocyte ratio

-

Thrombocytopenia

-

Hematologic manifestations may be confused with dengue infection

-

Elevated transaminase levels (75-95% of patients)

-

Hypoalbuminemia (50% of cases)

Laboratory studies of choice are serologic tests for antibodies, including the following:

-

Indirect immunoperoxidase test

-

Indirect fluorescent antibody test

-

Dot immunoassay

-

Rapid immunochromatographic tests for detection of IgM and IgG

-

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay

-

Rapid diagnostic reagent for scrub typhus

-

Weil-Felix OX-K strain agglutination reaction

Chest radiography may reveal pneumonitis, especially in the lower lung fields.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Current treatment for scrub typhus is based on antibiotic therapy. Relapses may occur if the antibiotics are not taken for long enough. Agents that have been used include the following:

-

Tetracycline derivatives (standard; especially doxycycline)

-

Macrolides (eg, azithromycin, roxithromycin, and telithromycin)

-

Fluoroquinolones (not currently recommended; results have been mixed)

Diet and activity are as tolerated. Inpatient care may be necessary for patients with severe scrub typhus. In such cases, meticulous supportive management is necessary to abort progression to DIC or circulatory collapse.

Preventive measures in endemic areas include the following:

-

Protective clothing

-

Insect repellents

-

Short-term vector reduction using environmental insecticides and vegetation control

Chemoprophylaxis regimens have included the following:

-

A single dose of doxycycline given weekly, started before exposure and continued for 6 weeks after exposure [1]

-

A single oral dose of chloramphenicol (typically not used in the United States) or tetracycline given every 5 days for a total of 35 days, with 5-day nontreatment intervals

No vaccine is available.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Scrub typhus is an acute, febrile, infectious illness that was first described in China in 313 AD. It is caused by Orientia (formerly Rickettsia) tsutsugamushi, an obligate intracellular gram-negative bacterium, which was first isolated in Japan in 1930. Although scrub typhus was originally recognized as one of the tropical rickettsial diseases, O tsutsugamushi differs from the rickettsiae with respect to cell-wall structure and genetic composition.

The term scrub typhus derives from the type of vegetation (ie, terrain between woods and clearings) that harbors the vector. However, this term is not entirely accurate, in that scrub typhus can also be prevalent in areas such as sandy beaches, mountain deserts, and equatorial rain forests.

US cases have been imported from regions of the “tsutsugamushi triangle,” which extends from northern Japan and eastern Russia in the north to northern Australia in the south and to Pakistan and Afghanistan in the west, where the disease is endemic. The range includes tropical and temperate regions, extending to altitudes greater than 3200 meters in the Himalayas. Scrub typhus is often acquired during occupational or agricultural exposures [2] because active rice fields are an important reservoir for transmission. [3]

Western medicine became especially interested in scrub typhus during military campaigns fought in East Asia. During World War II, 18,000 cases were observed in Allied troops stationed in rural or jungle areas of the Pacific theatre. [3] Scrub typhus was the second or third most common infection reported in US troops stationed in Vietnam [4] and still infects troops in the region. [5, 6] The US military continues to work on vector control, more accurate diagnostic tests, better vaccines, and improved surveillance methods. [7]

Currently, it is estimated that about 1 million cases of scrub typhus occur annually and that as many as 1 billion people living in endemic areas may have been infected by O tsutsugamushi at some time. [6] Because of reports of O tsutsugamushi strains with reduced susceptibility to antibiotics, [8] as well as reports of interesting interactions between this bacterium and HIV, a renewed interest in scrub typhus has emerged. [9, 10]

Pathophysiology

O tsutsugamushi, the pathogen that causes scrub typhus, is transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected chigger (see the image below), the larval stage of Leptotrombidium mites. These 6-legged, 0.2-mm larvae are not host specific and feed for 2-10 days on the skin fluids of the host. Wild rats serve as the natural reservoir for the chiggers (and represent a risk factor for human infection [2] ), but they are rarely infected with O tsutsugamushi. [3] When the chiggers feed on humans, infection occurs.

Chigger. Image taken from "Food and Environmental Hygiene Department" Web site and is reproduced under license from the Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

Chigger. Image taken from "Food and Environmental Hygiene Department" Web site and is reproduced under license from the Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

Orientia is also transmitted transovarially in mites and can unbalance the sex ratio of offspring in favor of females, further propagating infection. [3, 11] Chigger activity and subsequent human infection rates are determined by the particular Leptotrombidium species present (eg, akamushi, deliense, or pallidum), as well as by local conditions. Not surprisingly, positive correlations have been noted between chigger population abundance and human cases of scrub typhus. [12]

In tropical regions, scrub typhus may be acquired year round. In Japan, the chigger of Leptotrombidium akamushi is only active between July and September, when the temperature is above 25°C (77°F). In contrast, Leptotrombidium pallidum, which is found over a wide range, is active at temperatures of 18-20°C (64.4-68°F), from spring into early summer and autumn. [3, 13]

Humans acquire scrub typhus when an infected chigger bites them while feeding and inoculates O tsutsugamushi pathogens. The bacteria multiply at the inoculation site, and a papule forms that ulcerates and becomes necrotic, evolving into an eschar, with regional lymphadenopathy that may progress to generalized lymphadenopathy within a few days. In experimental infection, humans developed an acute febrile illness within 8-10 days of the chigger bite. Bacteremia was present 1-3 days before onset of fever. [14]

As in rickettsial diseases, perivasculitis of the small blood vessels occurs. The endothelium is involved; however, the basic histopathologic lesions suggest that macrophages might be more affected. [15]

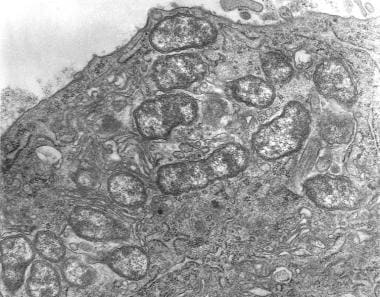

O tsutsugamushi stimulates phagocytosis by the immune cells, and then escapes the phagosome. It replicates in the cytoplasm (see the image below) and then buds from the cell. The bacteria are able to harness the microtubule assembly inside the human cell for movement. Antibody-opsonized bacteria are still able to escape the phagosome but cannot effectively move on the microtubule; as a result, overall infectivity is decreased. [3]

Transmission electron micrograph depicts peritoneal mesothelial cell of mouse that had been experimentally infected intraperitoneally with Orientia tsutsugamushi. Several organisms are visible within mesothelial cell's cytoplasm.

Transmission electron micrograph depicts peritoneal mesothelial cell of mouse that had been experimentally infected intraperitoneally with Orientia tsutsugamushi. Several organisms are visible within mesothelial cell's cytoplasm.

Scrub typhus may disseminate into multiple organs through endothelial cells and macrophages, resulting in the development of fatal complications. [16, 17] In 2009, an apparent association was reported apparent between high O tsutsugamushi blood polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-determined DNA loads and disease severity. [18]

Etiology

Scrub typhus is caused by O tsutsugamushi, an obligate intracellular gram-negative bacterium that lives primarily in L akamushi and L deliense mites . This organism is found throughout the mite’s body but is present in the greatest number in the salivary glands. When the mite feeds on rodents (eg, rats, moles, and field mice, which are the secondary reservoirs) or humans, the parasites are transmitted to the host. Only larval Leptotrombidium mites (chiggers) transmit the disease.

O tsutsugamushi is very similar to the rickettsiae and indeed meets all of the classifications of the genus Rickettsia; this connection is demonstrated by the high degree of homology (90-99%) on 16S ribosomal sequencing. However, the cell walls are quite different, in that those of O tsutsugamushi lack peptidoglycan and lipopolysaccharide. [3] This pathogen does not have a vacuolar membrane; thus, it freely grows in the cytoplasm of infected cells.

There are numerous serotypes, [19] of which 5—Karp, Gilliam, Kawazaki, Boryon, and Kato—are helpful in serologic diagnosis. About half of isolates are seroreactive to Karp antisera, and approximately one-quarter of isolates are seroreactive to antisera against the prototype Gilliam strain. [20]

Risk factors

In 2009, behavioral factors were shown to be associated with scrub typhus during an autumn epidemic season in South Korea. [21] Taking a rest directly on the grass, working in short sleeves, working with bare hands, and squatting to defecate or urinate posed the highest risks. Wearing a long-sleeved shirt while working, keeping work clothes off the grass, and always using a mat to rest outdoors showed protective associations.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Scrub typhus has no significant presence in the United States itself. The only cases of scrub typhus reported in the United States derive from elsewhere—for example, US travelers who have recently been to one of the endemic areas, military personnel who have been stationed abroad, or persons who have emigrated from other countries. [13, 22]

More recently, a study by Chen et al detected Orientia species in free-living Eutrombicula chiggers that were collected at recreational parks in North Carolina. [23]

International statistics

Scrub typhus is endemic in regions of eastern Asia and the southwestern Pacific (Korea to Australia) and from Japan to India and Pakistan. [2, 15, 24, 25, 26, 27] More recently, there have been increased reports of infection in Northern India and Chile. [28, 29]

It is generally a disease of rural villages and suburban areas and is normally not encountered in the cities.

Although most cases are undiagnosed, prospective studies in endemic areas reveal in incidence of 18-23%. [3, 30] Community surveys in Malaysia reported an incidence of 3.2-3.5% per month and a seroprevalence exceeding 80% in those older than 44 years. [31] Surveillance of military personal deployed in southeast Asia demonstrated seroconversion in 484 per 1000 population. [5]

The seasonal occurrence of scrub typhus varies with the climate in different countries because the mites are able to thrive as conditions change. The mites prefer the rainy season and certain areas (eg, forest clearings, riverbanks, and grassy regions). In the past few years, cases have been noted earlier in the season because of increased mite activity as the weather warms. [32] Areas in which mites thrive pose a greater risk to humans. The prevalence of scrub typhus in Japan has been rising, and much of the current research is based in Japan.

Age-, sex-, and race-related demographics

People of all ages are affected equally by scrub typhus. Men and women are affected with equal frequency. No race-related differences in incidence have been documented.

Prognosis

Prognosis varies and depends on the severity of illness, which relates to the different strains of O tsutsugamushi, as well as to host factors. Severe disease is uncommon with antimicrobial treatment. Prognostic indicators for severe disease have not been established. [33] Incomplete immunity and strain heterogeneity open the door to frequent reinfections. Immunity to the same strain is believed to last 3 years, whereas immunity to other strains may last as little as 1 month; however, repeat infections may be attenuated. [3]

In patients who are not treated, mortality ranges from 1% to 60%, depending on the patient’s age, the geographic area, and the particular strain responsible for the infection. In the preantibiotic era, mortality in Japan averaged 30%: 15% in patients aged 11-20 years, 20% in those aged 21-30 years, and 59% in those older than 60 years. In Taiwan, overall mortality was estimated at 11% but was only 5% in children and 45% in the elderly.

With appropriate antibiotic treatment, mortality from scrub typhus is quite rare, and the recovery period is short and usually without complications. [3, 32] However, mortality is still approximately 15% in some areas as a consequence of missed or delayed diagnosis. [34] If severe complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) arise, mortality may still be high. [35]

Complications

Scrub typhus patients who are not treated may develop serious complications and may even die. Mortality ranges from 1% to 60%, depending on the geographic area and the pathogenic strain. Death can occur either from the primary infection or from secondary complications (eg, pneumonitis, encephalitis, or circulatory failure). Most fatalities occur by the end of the second week of infection.

Scrub typhus has an increased potential for complications when patients are older than 60 years, present without eschar, or have white blood cell (WBC) counts higher than 10,000/μL. [36] This condition represents an important cause of fever associated with poor pregnancy outcomes in refugee camps on the Thai-Burmese border. [37] Another study reported that more than a third of pregnant women with murine typhus or scrub typhus infection have poor neonatal outcomes. [38, 39]

A meta-analysis by Alam et al found an overall case fatality ratio (CFR) of 3.8% in patients with central nervous system manifestations of scrub typhus. The investigators reported that the CFR in the pediatric cohorts was 6.1%, and they suggest that mortality may be higher in children than in adults with neurologic complications. [40]

-

Transmission electron micrograph depicts peritoneal mesothelial cell of mouse that had been experimentally infected intraperitoneally with Orientia tsutsugamushi. Several organisms are visible within mesothelial cell's cytoplasm.

-

Eschar on neck.

-

Eschar on scrotum.

-

Typical eschar.

-

Maculopapular rash.

-

Chigger. Image taken from "Food and Environmental Hygiene Department" Web site and is reproduced under license from the Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.