Practice Essentials

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) (see the image below) is the leading cause of lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) in infants and young children. Each year, 4-5 million children younger than 4 years acquire an RSV infection, and more than 125,000 are hospitalized annually in the United States because of this infection. The impact of RSV infection is not limited to only young children. In United States, it is responsible for 177,000 hospitalizations and 14,000 deaths in the elderly ≥ 65 years of age. [1, 2]

Electron micrograph of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). RSV is most common cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia in children younger than 1 year. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Electron micrograph of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). RSV is most common cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia in children younger than 1 year. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Signs and symptoms

Patients with RSV infection may present with the following symptoms:

-

Upper respiratory tract infection (URTI)

Cough

Tachypnea

Cyanosis

Retractions

Wheezing

Rales

-

Fever (typically low-grade)

-

Sepsislike presentation or apneic episodes (in very young infants)

Physical examination of the infant with RSV-related LRTI may reveal the following:

-

Evidence of diffuse small airway disease

-

Associated otitis media (viral, bacterial, or both)

-

Dehydration (assessed by evaluating skin turgor, capillary refill, and mucous membranes)

RSV LRTI in infancy may be linked with subsequent reactive airway disease, although this association remains controversial.

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies generally are not indicated in the infant with bronchiolitis who is comfortable in room air, well hydrated, and feeding adequately. When warranted, nonspecific laboratory studies may include the following:

-

Complete blood cell (CBC) count

-

Serum electrolyte concentrations

-

Urinalysis

-

Oxygen saturation

Specific tests for RSV may be indicated for therapeutic decision making, isolation of patients, and educating parents and staff. Specific diagnostic tests for confirming RSV infection include the following:

-

Culture (human epithelial type-2 [HEp-2])

-

Antigen-revealing techniques (rapid turnaround time [30 mins])

-

Molecular probes (commonly used multiplex PCR assays)

Chest radiography is frequently obtained in children with severe RSV infection, but for the most part, typical findings are neither specific to RSV infection nor predictive of the course or outcome.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Supportive care is the mainstay of therapy for RSV infection. This includes supplemental oxygen when indicated, management of respiratory secretions and maintaining hydration. The Clinical Practice Guidelines published by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2014 does not recommend medications such as bronchodilators, epinephrine and corticosteroids as the available clinical data does not support their use in the treatment of typical RSV bronchiolitis. [3, 4]

Pharmacologic therapies for RSV infection include the following:

-

Bronchodilators – These benefit at least a subset of patients with RSV-related LRTI

-

Alpha agonists – These have been used during acute bronchiolitis episodes, though their efficacy has not been established

-

Ribavirin – This agent is primarily reserved for patients with significant underlying risk factors and severe acute RSV disease (eg, transplant recipients) but has unproven clinical benefit and based on high acquisition cost it is rarely administered

The following agents may be considered for passive immunization to protect against RSV infection:

-

Palivizumab (Synagis) - Indicated for prophylaxis in children at high risk for severe RSV disease

-

Nirsevimab (Beyfortus) - Indicated for prevention of RSV lower respiratory tract disease in neonates and infants born during or entering their first RSV season, and in children up to 24 months of age who remain vulnerable to severe RSV disease through their second RSV season

Another strategy for prevention of RSV infection in infants is through active immunization of pregnant women with the following:

-

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine (Abrysvo) is indicated for maternal vaccination at 32-36 weeks of gestation to help protect infants at birth through 6 months of life from lower respiratory tract disease (LRTD) and severe LRTD due to RSV

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends RSV vaccination for pregnant persons. [5]

According to American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) 2014 guidelines for RSV prophylaxis and renewed in 2018, the following are candidates for palivizumab prophylaxis:

-

Premature infants born before 29 weeks, 0 days’ gestation who are younger than 1 year chronological age at the start of the RSV season

-

Premature infants born before 32 weeks, 0 days’ gestation who are younger than 1 year chronological age at the start of the RSV season with chronic lung disease of prematurity defined as need for greater than 21 % oxygen for at least 28 days after birth

-

In the second year of life, for children who continue to require medical intervention (supplemental oxygen, chronic corticosteroid or diuretic therapy)

-

Infants younger than 24 months who have hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease (cyanotic or acyanotic lesions) requiring medications for heart failure or will need heart transplant or infants with moderate to severe pulmonary hypertension

Other measures proposed for preventive purposes include the following:

-

Vaccination: Improved understanding of the structure of RSV and the importance of the prefusion protein has led to a tremendous increase in RSV vaccine development over the past decade. Today there are 60 vaccine candidates in preclinical and clinical (phase 1-3) trials

-

Vitamin D supplementation (supplementation during pregnancy may ameliorate RSV LRTI during infancy)

-

Breastfeeding may also provide some protection against severe RSV disease

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Infection with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), which manifests primarily as bronchiolitis or viral pneumonia, is the leading cause of LRTIs in infants and young children. The clinical entity of bronchiolitis was described at least 100 years ago. In 1956, Morris and colleagues initially isolated RSV from chimpanzees with upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) and identified the virus as the causative agent of most epidemic bronchiolitis cases. Subsequently, RSV has been associated with bronchiolitis and LRTI in infants. Multiple epidemiologic studies have confirmed the role of this virus as the leading cause of LRTI in infants and young children.

The peak incidence of severe RSV disease is at age 2-8 months. Overall, 4-5 million children younger than 4 years acquire an RSV infection each year, and more than 125,000 are hospitalized annually in the United States because of this infection. Virtually all children have had at least 1 RSV infection by the age of 3 years. In view of the prevalence and potential severity of this condition, it is not surprising that the World Health Organization (WHO) has targeted RSV for vaccine development.

This article reviews aspects of the virology, epidemiology, clinical course, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of RSV-related illness.

For patient education resources, see the Cold and Flu Center, as well as Viral Pneumonia and Flu in Children.

Pathophysiology

RSV infection is limited to the respiratory tract. Initial infection in young infants or children frequently involves the lower respiratory tract and most often manifests as the clinical entity of bronchiolitis. Inoculation of the virus occurs in respiratory epithelial cells of the upper respiratory tract. Spread of the virus down the respiratory tract occurs through cell-to-cell transfer of the virus along intracytoplasmic bridges (syncytia) from the upper to the lower respiratory tract.

The illness may begin with upper respiratory symptoms and progress rapidly over 1-2 days to the development of diffuse small airway disease characterized by cough, coryza, wheezing and rales, low-grade fever (< 101°F), and decreased oral intake. A family history of asthma or atopy is frequently obtained. [6, 7] In more advanced disease, retractions and cyanosis may be noted, and as many as 20% of patients may develop higher temperatures.

The incidence of concomitant or secondary serious bacterial infection in association with RSV infection appears to be quite low (< 1%), with the exception of otitis media, which may occur in as many as 40% of cases. In very young infants, apnea out of proportion to respiratory signs and symptoms may be present, and in infants younger than 6 weeks, a relatively nonspecific sepsislike picture has been described. [8]

Reinfection with RSV occurs at all ages; however, with recurrent infection and increasing age, RSV infections are more likely to be limited to the upper respiratory tract. RSV URTI is more severe than the common cold, as evidenced by the 7- to 10-day duration of illness and by the finding from one study of adults with RSV that the mean absence from work is 6 days. Studies have also demonstrated severe RSV disease in elderly persons. [9]

Etiology

In the community setting, a number of factors have been associated with an increased risk of acquiring RSV disease, including the following:

-

Childcare attendance

-

Older siblings in preschool or school

-

Crowding and lower socioeconomic status

-

Exposure to environmental pollutants (eg, cigarette smoke)

-

Multiple birth sets (especially triplets or greater)

-

Minimal breastfeeding

In infants with RSV infection, the following factors have been correlated with more severe disease and the need for hospitalization.

-

Prematurity. Even though the greatest risk for severe disease is in premature infants born at ≤ 29 week gestation, recent data continues to demonstrate increased risk up to 35 weeks gestation. [10]

-

Age younger than 3 months at the time of infection

-

Chronic lung disease

-

Congenital heart disease

-

Congenital immunodeficiency (eg, severe combined immunodeficiency [SCID])

-

Severe neuromuscular disease

-

Toxic appearance at time of presentation

-

Respiratory rate higher than 70 breaths/min on room air

-

Atelectasis or pneumonitis on chest radiography

-

Oxygen saturation lower than 95% on room air

Although infants in these groups are at higher risk for severe RSV disease than are normal full-term infants in terms of percentages, many more children in the normal full-term group are admitted to the hospital; thus, most admissions for RSV disease occur in otherwise normal infants. A family history of asthma and genetic factors are also correlated with more severe RSV disease, though the exact relations and mechanisms have not been elucidated.

A multicenter SENTINEL 1 study by Anderson et al reported that preterm infants 29 to 35 weeks gestational age are at high risk for severe respiratory syncytial virus. In the study, of the 702 infants who were hospitalized with community-acquired RSV disease, 42% were admitted to the ICU and 20% required invasive mechanical ventilation. Sixty-eight percent of the infants 29 to 32 weeks gestational age and under 3 months of age required ICU admission and 44% required invasive mechanical ventilation. [11]

Epidemiology

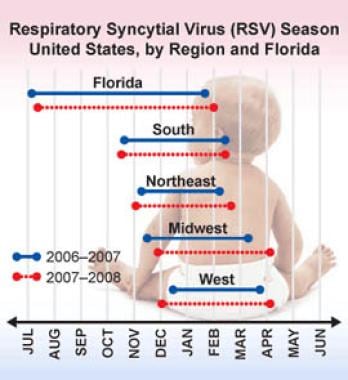

RSV LRT infection develops annually in 4-5 million children, and more than 125,000 children are admitted per year for RSV-related illness. The burden of RSV infection is not limited to only young children. In United States, it is responsible for 177,000 hospitalizations and 14,000 deaths in elderly ≥ 65 years of age. [1, 2] Seasonal variations in incidence are observed (see the image below). Reinfection occurs throughout life, with the disease generally limited to the upper respiratory tract in persons older than 3 years. RSV infection is primarily seen in the winter months throughout United States except in the state of Florida where it extends throughout much of the year. Nationally the onset of RSV season ranges from mid-September to mid-November, peaks from mid-December to mid-February, and the off-season occurs mid-April to mid-May. In tropical climates peak RSV activity correlates with the rainy season.

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the typical patterns of circulation for RSV. Starting in the southern United States, RSV circulation increased during the spring of 2021 and peaked in the summer. [12]

Severe RSV disease has been reported in older children and adults with SCID (eg, bone marrow transplantation), and RSV disease of the lower respiratory tract has been reported in elderly persons. RSV infection can also be severe in adults with COPD, those with immunodeficiency, and those ≥ 65 years of age.

Respiratory syncytial virus infection season, United States, by region and Florida. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Respiratory syncytial virus infection season, United States, by region and Florida. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Worldwide, RSV infection is prevalent, with clinical manifestations and early occurrence of RSV LRTI comparable to those seen in the United States. [2] Each year RSV infection causes more than 100,000 deaths among children younger than 5 years throughout the world. Nearly half of those deaths occur in infants younger than 6 months old. In addition, RSV infection accounts for an estimated 3.6 million hospital admissions globally each year. [13, 14]

Severe RSV disease is primarily a disease of young infants and children, with a peak occurrence at the age of 2-8 months. Reinfection with RSV occurs throughout life, with disease becoming increasingly limited to the upper respiratory tract with advancing age. Although boys and girls are equally affected by milder RSV disease, males are approximately twice as likely to be hospitalized for RSV disease. All races appear to be susceptible to RSV, showing similar disease patterns.

Prognosis

Children hospitalized secondary to RSV infection typically recover and are discharged in 3-4 days. High-risk infants remain hospitalized longer and have higher rates of admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and of mechanical ventilation.

Morbidity/mortality

Even in children hospitalized with RSV infection, mortality is less than 1%, and fewer than 500 deaths per year are attributed to RSV in the United States. However, in select groups of high-risk patients, appreciable mortality and increased morbidity still may result from this infection. [15, 16, 17]

Infants with chronic lung disease of infancy (ie, bronchopulmonary dysplasia), congenital heart disease, or marked prematurity when hospitalized for this disease may have a 3-5% mortality rate. Additionally, such infants and patients with immunodeficient states have been shown to spend, on average, twice as long in the hospital as other patients with RSV infection (7-8 days vs 3-4 days in normal full-term infants).

Additionally, children hospitalized for RSV disease during infancy have higher rates of subsequent wheezing than age-matched controls not hospitalized for this condition over the next 10 or more years. Whether RSV itself leads to alterations of airways or immune responses contributing to these subsequent events or is just a marker for children at risk for reactive airway disease remains incompletely understood.

Complications

Infants hospitalized for RSV LRTI in infancy are at higher risk for subsequent wheezing and abnormal pulmonary function tests than age-matched control subjects who did not have such an admission, and this increased risk may persist for up to 10 years or longer.

RSV’s role in causing subsequent reactive airway disease remains controversial. Several small studies have suggested that infants who are hospitalized with RSV infection and treated with ribavirin have better pulmonary function on follow-up than infants who are not. If this finding is confirmed, it should help elucidate the link between RSV LRTI in infancy and subsequent reactive airway disease. Analyses comparing recipients of RSV prophylaxis with nonrecipients may also help answer this clinically important question. [18, 19]

A study by Kitsantas et al that included the records of 1,542 infants reported that approximately 10% of the children developed asthma and more than 9% developed hay fever or respiratory allergy by age 6. [20]

-

Respiratory syncytial virus infection season, United States, by region and Florida. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Electron micrograph of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). RSV is most common cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia in children younger than 1 year. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.