Practice Essentials

Sexual activities imposed on children represent an abuse of the caregiver's power over the child. The sequence of activities often progresses from noncontact to contact over a period of time during which the child's trust in the caregiver is misused and betrayed.

Pediatricians are often in trusted relationships with patients and families and are in an ideal position to offer essential support to the child and family. Thus, pediatricians need to be knowledgeable about available community resources, such as consultants and referral centers for the evaluation and treatment of sexual maltreatment.

Signs and symptoms

In incidents of child sexual abuse (CSA), the interview with the child is typically the most valuable component of the medical evaluation; the elicited history is frequently the only diagnostic information that is uncovered.

Elements of the history include the following:

-

General approach that is developmentally sensitive (ie, age-appropriate)

-

Initial introduction with efforts to build up trust (including both child and caregiver)

-

Caregiver interview

-

Child interview, focusing on asking simply worded, open-ended, nonleading questions

-

Wrap-up and preparation for the physical examination

The general approach to the physical examination follows the standard head-to-toe approach. Elements of the examination include the following:

-

Determination of structures of interest – Mons pubis, labia majora and minora, clitoris, urethral meatus, hymen, posterior fourchette, and fossa navicularis

-

Choice of positioning for optimal exposure of prepubertal genital structures – Frog-leg supine position, knee-chest position, or left lateral decubitus position

-

Calming the child during examination

-

General observation and inspection of the anogenital area, looking for signs of injury or infection and noting the child’s emotional status

-

Visualization of the more recessed genital structures, using handheld magnification or colposcopy as necessary

-

Collection of specimens for sexually transmitted disease (STD) screening and forensic evidence collection

-

Evaluation of any observable findings – Although most individuals who have been sexually abused present with essentially normal examination findings, observable findings may include (1) those attributable to acute injury or (2) chronic findings that may be residual effects following repeated episodes of genital contact

The Muram diagnostic categorization system classifies prepubertal genital examination findings as follows:

-

Category I - Genitalia with no observable abnormalities

-

Category II - Nonspecific findings that are minimally suggestive of sexual abuse but also may be caused by other etiologies

-

Category III - Strongly suggestive findings that have a high likelihood of being caused by sexual abuse

-

Category IV - Definitive findings that have no possible cause other than sexual contact (eg, seminal products in a prepubertal female child’s vagina, the presence of a nonvertically transmitted gonorrhea or syphilis infection)

Another classification system, developed by Adams et al on the basis of the Muram approach combined with information from other components of the sexual abuse assessment, includes the following 8 categories of findings: [1, 2, 3]

-

Findings documented in newborns or commonly seen in nonabused children (ie, normal variants)

-

Findings commonly caused by other medical conditions

-

Findings with no expert consensus on interpretations with respect to sexual contact or trauma (formerly Indeterminate findings)

-

Findings diagnostic of trauma and/or sexual contact

-

Residual or healing injuries

-

Injuries of blunt force penetrating trauma

-

Infection that confirms mucosal contact with infected bodily secretions (ie, indicating that contact was most likely sexual)

-

Findings diagnostic of sexual contact (ie, pregnancy or sperm directly taken from a child’s body)

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Cultures have traditionally been the criterion standard for cases of possible sexual abuse and are valuable from a forensic evidence standpoint. Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) has been used widely in the sexually active adolescent and adult populations secondary to its higher sensitivity, noninvasive sample collections, and its utility in testing for both Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis with one sample, and its lower cost compared to culture. [4] NAATs can be used as an alternative to culture with vaginal specimens or urine from girls whereas culture remains the preferred method for urethral specimens or urine from boys and for extra-genital specimens for all children. [5]

-

Gram stain of vaginal or anal discharge

-

Genital, anal, and pharyngeal culture for gonorrhea

-

Genital and anal culture for chlamydia

-

See above regarding NAAT (Chlamydia, N. gonorrhea)

-

Serology for syphilis

-

Culture by using Diamond’s or InPouch TV media (most specific method of diagnosing Trichomonas vaginalis) [6]

-

Wet prep of vaginal discharge for Trichomonas vaginalis, other bacteria, candida, etc.

-

Culture of lesions for herpes virus

-

Serology for HIV (based on suspected risk)

Other tests that may be considered include the following:

-

Collection of forensic evidence via rape kit

-

Urine toxicology screen (if the abuse or assault was substance-facilitated)

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Medical treatment of CSA is guided by any conditions uncovered. Recommendations include the following:

-

Treat STDs with appropriate medications

-

In postmenarchal children, consider the possibility of pregnancy

-

Recognize the overriding need for emotional support and attention

-

When sexual abuse is seriously suspected or has been diagnosed, ensure that it is reported to the appropriate child protective services (CPS) agency

-

When sexual abuse is being considered, consider reporting it, depending on the perceived risk to the child

-

Keep well-documented medical records; legal proceedings may occur over long periods, and the health care provider cannot rely solely on memory

Mental health consultation is warranted to evaluate and treat acute stress reaction and, later, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Child sexual abuse (CSA) refers to the use of children (persons younger than 18 years old) in sexual activities when, because of their immaturity and developmental level, they cannot understand or give informed consent. A wide range of activities is included in sexual abuse, including contact and noncontact activities. Contact activities include sexualized kissing, fondling, masturbation, and digital and/or object penetration of the vagina and/or anus, as well as oral–genital, genital–genital, and anal–genital contact. Noncontact activities include exhibitionism, inappropriate observation of child (eg, while the child is dressing, using the toilet, bathing), the production or viewing of pornography, or involvement of children in prostitution.

The sexual activities are imposed on the child and represent an abuse of the caregiver's power over the child. The sequence of activities often progresses from noncontact to contact over a period of time during which the child's trust in the caregiver is misused and betrayed. The image below depicts suture in place at 6-o'clock position to stop bleeding from injury.

Genital examination of girl in frog-leg supine position after genital trauma. Examination reveals suture in place at 6-o'clock position to stop bleeding from injury. Hymenal edge is irregular and asymmetric. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

Genital examination of girl in frog-leg supine position after genital trauma. Examination reveals suture in place at 6-o'clock position to stop bleeding from injury. Hymenal edge is irregular and asymmetric. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

Since the mid-1970s, healthcare professionals have paid serious attention to sexual abuse of children. Despite the recognition of the clinical importance of sexual abuse of children, some pediatricians may not feel adequately prepared to perform medical evaluations. However, pediatricians are often in trusted relationships with patients and families and are in an ideal position to offer essential support to the child and family. Thus, pediatricians need to be knowledgeable about available community resources, such as consultants and referral centers for the evaluation and treatment of sexual maltreatment. One study evaluated residents' and practicing physicians' medical knowledge of child abuse and maltreatment. Using a 30-question survey, the results found an overall average score of 63.3%; these findings highlight the need for increased education in child maltreatment. [7]

Several paradigms have been proposed to help professionals understand the events that surround the sexual maltreatment of children.

Preconditions for sexual abuse

See the list below:

-

Motivation of perpetrator: The perpetrator is willing to act on impulses associated with sexual arousal related to children.

-

Overcoming internal inhibitions: The perpetrator ignores internal barriers against sexually abusing children.

-

Overcoming external inhibitions: The perpetrator is able to bypass the typical barriers in the caregiving environment that normally serve to impede the sexual misuse of children.

-

Overcoming child resistance: The perpetrator is able to manipulate the child to the point of involving the child in the sexual activity. Manipulation often involves either implicit or explicit coercion to ensure that the child keeps the inappropriate activities a secret. [8]

Longitudinal progression of sexual abuse

See the list below:

-

Engagement: The perpetrator begins relating to the child during nonsexual activities to gain the child's trust and confidence.

-

Sexual interaction: The perpetrator introduces sexual activities into the relationship with the child; the perpetrator often begins with noncontact types of activities and, over time, progresses to more invasive forms of contact activities.

-

Secrecy: The perpetrator attempts to maintain access to the child and to avoid disclosure of the abuse by coercing the child to keep the activities hidden. Coercion to keep the secret can be explicit (eg, threatening the child or the child's family's safety) or it can be implicit (eg, manipulation of the child's trust to create a fear of losing the "friendship" or "attention" should the truth become known to others).

-

Disclosure: Sexual abuse can become known to others either accidentally, when a symptom from the maltreatment or a third party witnessing the abuse leads to an evaluation, or can be purposeful, as when the child reveals the abuse that is taking place and seeks help.

-

Suppression: The tumult that occurs after the disclosure prompts the people in the child's caregiving environment to think that they are unable to support the child; thus, these people exert pressure on the child to recant what the child has told in order to go back to the perceived "stable" situation that existed prior to the disclosure.

Sexual abuse typically presents as a pattern of maltreatment that occurs over time. Children or their families usually know the perpetrators, because they often are either relatives or acquaintances. [9]

Traumagenic dynamics model

See the list below:

-

Traumatic sexualization: The child's sexual feelings and attitudes are shaped in a developmentally inappropriate and interpersonally dysfunctional manner. The child learns that sexual behavior may lead to rewards, attention, or privileges. Traumatic sexualization may also occur when the child's sexual anatomy is given distorted importance and meaning.

-

Betrayal: The child learns that a trusted individual has caused him or her harm, misrepresented moral standards, or failed to protect him or her properly.

-

Powerlessness: This is a process of disempowerment in which the child's sense of self-efficacy and will are consistently thwarted by the perpetrator's coercion and manipulation. The child manifests symptoms of fear, anxiety, and impaired coping.

-

Stigmatization: The child's self-image incorporates negative connotations and is associated with words such as bad, awful, shameful, and guilty. This stigmatization is consistent with the "damaged goods" mentality originally described by Sgroi et al (1982), in which the child feels deviant and not as whole as he or she felt prior to the abuse. [9, 10]

Pathophysiology

The evaluation for suspected sexual abuse may be complicated and is often not straightforward. Frequently, nonspecific behavioral changes are the presenting symptoms prompting an evaluation and leading the health care provider to consider sexual abuse as a possible diagnosis. These nonspecific behaviors are not diagnostic of sexual maltreatment and may be observed in other situations where the child manifests stress as well. Nonspecific behavior changes that warrant consideration of the possibility of sexual abuse may include (1) sexualized behaviors, (2) phobias, (3) sleep disturbances, (4) changes in appetite, (5) change in or poor school performance, (6) regression to an earlier developmental level, (7) running away, (8) truancy, (9) aggressiveness and acting out behaviors, and/or (10) social withdrawal, sadness, or symptoms of depression.

One study identified a screening tool to identify which prepubertal children (≤ 12 y) should receive an initial evaluation for alleged sexual assault in a nonemergent setting, as opposed to one in the emergency department. [11] A positive screen, which warranted an immediate evaluation, was considered if an affirmative response was received to any of the following questions:

-

Did the incident occur in the past 72 hours, and was there oral or genital to genital/anal contact?

-

Was genital or rectal pain, bleeding, discharge, or injury present?

-

Was there concern for the child's safety?

-

Was an unrelated emergency medical condition present?

This screening tool showed sensitivity of 100% and may help determine which children do not require evaluation in an emergency department for alleged sexual assault. [11]

When physical signs and symptoms are present, the best procedure is to generate an extensive differential diagnosis, progress through a careful workup to exclude the diagnostic options, and, eventually, arrive at a diagnosis. Numerous medical conditions can mimic the possible findings in persons who have been sexually abused; these may be considered as primarily being in the category II nonspecific findings group as proposed in the Clinical section. An organized approach to the diagnostic process is most useful.

For the purposes of this discussion, the differential diagnosis for each of the following 4 genital findings known to be associated with child sexual abuse is discussed.

Genital bleeding

Identification of the source for the blood is necessary to exclude serious injury. Blood-tinged vaginal or urethral discharge initially may be confused with frank bleeding. Differential diagnoses are as follows:

-

Local factors, such as injury (either accidental or nonaccidental) and/or foreign body irritation (eg, small toy parts, clumped toilet tissue [see the images below])

Prepubertal girl with foul-smelling bloody discharge. On examination, a foreign body in the vagina was found just past the hymenal orifice. The foreign body is lodged in vagina and appears to be toilet tissue that is colonized with bacteria, causing a vulvovaginitis. The foreign body was dislodged with gentle water flushing during examination. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

Prepubertal girl with foul-smelling bloody discharge. On examination, a foreign body in the vagina was found just past the hymenal orifice. The foreign body is lodged in vagina and appears to be toilet tissue that is colonized with bacteria, causing a vulvovaginitis. The foreign body was dislodged with gentle water flushing during examination. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

Genital examination of prepubertal girl with foul-smelling bloody discharge. On examination, a foreign body in the vagina was found lodged just past the hymenal orifice and appears to be toilet tissue that is colonized with bacteria, causing a vulvovaginitis. The foreign body was dislodged with gentle water flushing during examination. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

Genital examination of prepubertal girl with foul-smelling bloody discharge. On examination, a foreign body in the vagina was found lodged just past the hymenal orifice and appears to be toilet tissue that is colonized with bacteria, causing a vulvovaginitis. The foreign body was dislodged with gentle water flushing during examination. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

Dermatologic conditions, such as lichen sclerosis and/or dermatitis (eg, atopic, contact, seborrhea)

-

Infections, including sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), fungal infections, and/or nonspecific vulvovaginitis

-

Endocrinologic causes, such as estrogen withdrawal as observed in the neonate and/or precocious puberty

-

Neoplastic tissue, such as sarcoma botryoides

-

Structural abnormalities, such as vulvar hemangioma

Vaginal discharge

Normal physiologic clear-white mucoid discharge (ie, leukorrhea) should be differentiated from pathologic discharges. Differential diagnoses are as follows:

-

Local irritation from abusive sexual contact, foreign body, chemical irritants, and restrictive clothing

-

Infections, including STDs, fungal infections, nonspecific vulvovaginitis, group A streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Mycoplasma species

-

Physiologic leukorrhea

-

Structural abnormality, such as ectopic ureter, fistula, and draining pelvic abscess

Anogenital bruising

Bruising in the anogenital area most often represents some type of anogenital trauma, either accidental or abusive in origin. Differential diagnoses are as follows:

-

Local injury, including straddle injury, accidental impaling injury, accidental blunt trauma, and abusive injury

-

Dermatologic conditions, such as mongolian spots, lichen sclerosis, and vascular nevi

-

Systemic manifestations of other disorders, such as bleeding diathesis and vasculitis

Anogenital redness

This finding typically represents the result of inflammation. Differential diagnoses are as follows:

-

Local irritation from sexual abuse, poor hygiene, restrictive clothing, and chemicals

-

Anatomic/structural factors such as perianal fissuring and rectal prolapse

-

Dermatologic conditions, such as lichen sclerosus, psoriasis, and dermatitis (atopic, contact, seborrhea)

-

Infections, such as STDs, nonspecific vulvovaginitis, pinworm, scabies, fungal infections with Candida species, and perianal cellulitis or warts

-

Systemic manifestations of other disorders, such as Crohn disease, Kawasaki syndrome, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome

Frequency

Prevalence

Professionals conservatively use child sexual abuse (CSA) prevalence estimates of 20% in women and 5–10% in men. A classic prevalence study of New England male and female college students done by Finkelhor, which used a definition that included both contact and noncontact abuse with older perpetrators and children younger than 17 years, revealed that 19.2% of female students (1 in 5 women) and 9% of male students (1 in 10 men) reported sexual misuse during their childhoods. [12] These figures are believed to be conservative estimates; other studies using different methodologies support using these figures as reasonable prevalence estimates. Analysis by various experts of 16 prevalence studies of nonclinical North American samples supports setting the upper end of prevalence figures at about 17% for women and 8% for men.

Incidence

According to the US federal government’s official report, Child Maltreatment 2019, approximately 656,000 children were determined to be victims of child abuse and neglect; the overall child maltreatment rate was 8.9 victims per 1000 children in the population. [13] The data show that 74.9% of victims were neglected, 17.5% were physically abused, and 9.3% were sexually abused. For federal fiscal year 2019, approximately 3.5 million children received either an investigation or alternative response at a rate of 47.2 children per 1000 in the population. The number of children who received a CPS response increased nationally by 3.5% from 2015 to 2019.

The Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS-4) was mandated by the Keeping Children and Families Safe Act of 2003 (P.L. 108-36) and aimed to estimate the current national incidence, severity, and demographic distribution of child abuse and neglect in the United States based on standardized research definitions. [14] The NIS-4 collected data from a nationally representative sample of 122 counties in 2 phases (2005 and 2006). The NIS-4 is the single most comprehensive source of information about the current incidence of child abuse and neglect in the United States and is based on a nationally representative sample.

The NIS-4 used 2 sets of standardized definitions of maltreatment. Children identified under the “Harm Standard” were considered to be maltreated only if they had already experienced demonstrable harm or injury from the abuse or neglect. The second set (the “Endangerment Standard”) included those children identified under the Harm Standard as well as those who experienced abuse or neglect that put them at risk of harm.

Compared with the NIS-3 (1993), [15] the NIS-4 (2005/2006) reflected a 26% decline in the rate of overall Harm Standard maltreatment, as the incidence rate fell from 23.1 cases to 17.1 cases per 1000 children in the population. The overall incidence of children who experienced maltreatment, under the Endangerment Standard, displayed no statistical change since the NIS-3. While significant decreases in the incidence of overall abuse and all specific categories of abuse were noted, a significant increase in the incidence of emotional neglect was observed.

The NIS-4 reported an estimated sexual abuse incidence rate of 1.8 cases per 1000 (or a total of 135,300); this represented 24% of the total number of children known to have been abused. The NIS-4 used a definition that subsumed a range of behaviors, including intrusion, child’s prostitution or involvement in pornography, genital molestation, exposure or voyeurism, providing sexually explicit materials, failure to supervise the child’s voluntary sexual activities, attempted or threatened sexual abuse with physical contact, and unspecified sexual abuse.

The 2005/2006 NIS-4 incidence figure of 1.8 cases per 1000 children represents a statistically significant decrease (44%) in the rate of sexual abuse from the 1993 NIS-3, from 3.2 children per 1000 in 1993 to 1.8 children per 1000 in 2005-2006. The incidence of Harm Standard physical abuse and emotional abuse also decreased since the NIS-3, but those decreases did not match the sexual abuse decrease, either in size or in statistical strength. The number of children who experienced physical abuse decreased by 15%, whereas the number who suffered emotional abuse decreased by 27%. The decreases in incidence rates were 23% for physical abuse (from 5.7 cases to 4.4 cases per 1000 children) and 33% for emotional abuse (from 3.0 cases to 2.0 cases per 1000 children).

The NIS-4 Harm Standard estimates for physical, sexual, and emotional abuse do not differ statistically from the NIS-2 Harm Standard (1986) estimates for the component categories of abuse. Thus, the decreases since 1993 in the categories of Harm Standard abuse have returned their incidence rates to levels that are statistically equivalent to what they were at the time of the NIS-2 in 1986.

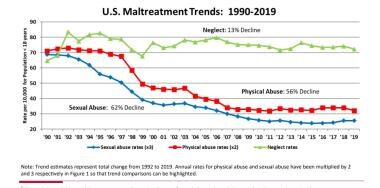

Finkelhor, Saito, and Jones at the Crimes Against Children Research Center have been tracking trends in child maltreatment statistics collected by the US government and have found a national decline in the incidence of both physical and sexual abuse that began in the middle of the 1990s and continued through 2019. [16]

US Maltreatment Trends, 1990-2019. Courtesy of David Finkelhor, PhD [Finkelhor D, Saito K, Jones L. Updated Trends in Child Maltreatment, 2019. Crimes Against Children Research Center, University of New Hampshire. February 2021. Online at: http://unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/CV203%20-%20Updated%20trends%202019_ks_df.pdf.].

US Maltreatment Trends, 1990-2019. Courtesy of David Finkelhor, PhD [Finkelhor D, Saito K, Jones L. Updated Trends in Child Maltreatment, 2019. Crimes Against Children Research Center, University of New Hampshire. February 2021. Online at: http://unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/CV203%20-%20Updated%20trends%202019_ks_df.pdf.].

Child neglect saw a 13% decline in 2019, and sexual abuse substantiations have seen a 62% downward trend from the peak annual incidence observed in 1992. There was an overall decline in physical abuse of 56% in 2019.

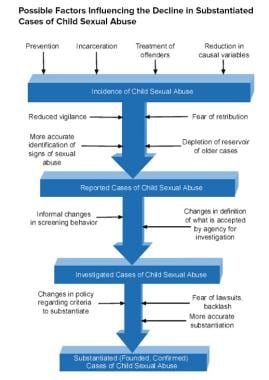

Finkelhor and Jones, over the years, have explored potential reasons for the decline in child sexual abuse and have focused on factors that may be impacting the actual incidence, as well as factors that may be influencing the reporting and investigation of reported cases, which may then downstream the number of substantiated cases. The possibility for the reported decline in child sexual abuse may result from change in attitudes, policies, and standards for reporting and investigating. These changes might account for some of the decline but they would not represent the entire picture. They indicate the need for a more balanced and questioning approach since decreasing trends in child sexual abuse are less clear (see image below). [17]

Possible factors influencing the decline in substantiated cases of child sexual abuse. Courtesy of David Finkelhor, PhD.

Possible factors influencing the decline in substantiated cases of child sexual abuse. Courtesy of David Finkelhor, PhD.

Optimistically, prevention efforts, incarceration, and treatment of perpetrators (along with other societal factors) may actually be decreasing the number of children who are harmed by sexual abuse. On the other hand, more pessimistically, fears of lawsuits and retribution, higher thresholds set for investigation and substantiation, and changes in policies and procedures may be changing the numbers but not impacting the actual amount of children under abuse.

No consensus has been reached about what may be causing the steady decline; Finkelhor and Jones draw attention to the idea that factors such as increasing economic prosperity, increasing numbers of agents of social intervention, and increasing availability of highly effective psychiatric medications may very well be leading to a decline in incidence with a resultant decline in substantiations.

Mortality/Morbidity

Numerous psychological and medical consequences have been described as associated with sexual abuse. Psychological disorders are reported as having an increased incidence in those who have been abused sexually and include depression, eating disorders, anxiety disorders, substance abuse, somatization, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), dissociative disorders, psychosexual dysfunction in adulthood, and numerous interpersonal problems, including difficulties with issues of control, anger, shame, trust, dependency, and vulnerability.

PTSD and its relationship to sexual abuse have received considerable professional attention. The diagnosis of PTSD in the context of sexual abuse requires the occurrence of maltreatment and (1) frequent reexperiences of the event via intrusive thoughts and/or nightmares; (2) avoidance behavior and a sense of numbness toward common events; and (3) increased arousal symptoms, such as jumpiness, sleep disturbance, and/or poor concentration. Note that no universal short-term or long-term impact of sexual abuse has been identified, and the presence or absence of various symptoms or conditions does not indicate nor disprove the occurrence of sexual abuse.

Medical sequelae of sexual abuse include numerous medical conditions, including functional GI disorders (eg, irritable bowel syndrome, dyspepsia, chronic abdominal pain), gynecologic disorders (eg, chronic pelvic pain, genital or anal tears), and various forms of somatization involving neurologic conditions and pain syndromes. Additionally, children may contract STDs via sexual abuse, and postpubertal females may become pregnant.

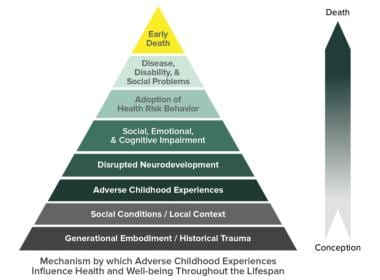

In groundbreaking work, Felitti et al explored the connection of exposure to childhood abuse and household dysfunction to subsequent health risks and the development of illness in adulthood in a series of studies referred to as the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) studies. [18] Of 13,494 adults who completed a standard medical evaluation in 1995 and 1996, 9,508 completed a survey questionnaire that asked about their own childhood abuse and exposure to household dysfunction; the investigators then made correlations to risk factors and disease conditions.

In order to assess exposure to child abuse and neglect, the ACE questionnaire asked about categories of child maltreatment, specifically psychological, physical, and sexual abuse. When asking about sexual abuse, the questionnaire asked the patients if an adult or person at least 5 years older then had ever (1) touched or fondled them in a sexual way; (2) made them touch the adults or older person’s body in a sexual way; (3) attempted oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse with them; or (4) actually had oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse with them. In order to assess exposure to household dysfunction the ACE questionnaire asked questions by category of dysfunction, such as having a household member who had problems with substance abuse (eg, problem drinker, drug user), mental illness (eg, psychiatric problem), or criminal behavior (eg, incarceration) and having a mother who was treated violently.

In addition to the questionnaire information, the standardized medical examination of the adult assess risk factors and actual disease conditions. The risk factors included smoking, severe obesity, physical inactivity, depressed mood, suicide attempts, alcoholism, any drug abuse, a high lifetime number of sexual partners, and a history of STDs. The disease conditions included ischemic heart disease, cancer, stroke, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, diabetes, hepatitis, and skeletal fractures. Once all of the data were collected and analyzed, Felitti et al reported that the most prevalent ACE was substance abuse (25.6%), the least prevalent ACE was criminal behavior (3.4%), and the prevalence of sexual abuse was 22%. In total, 52% of the respondents to the questionnaire had one or more exposure, and 6.2% of respondents had 4 or more exposures. The following were findings in respondents who experienced 4 or more ACEs compared with those who had none:

See the list below:

-

Risk of alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, and suicide attempt increased 4-12 fold

-

Rates of smoking, poor self-rated health, and high number of sexual partners and STDs increased 2-4 fold

-

Physical inactivity and severe obesity increased 1.4-1.6 fold

The major finding of the ACE studies was a graded relationship between the number of exposures to maltreatment and household dysfunction during childhood to the presence in later life of multiple risk factors and several disease conditions associated with death in adulthood. The image below graphically depicts the hypothesized connection between ACEs and later risk-taking behaviors and the development of life-threatening conditions.

Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Pyramid. Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html].

Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Pyramid. Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html].

Race

White and black children differed significantly in their rates of experiencing overall maltreatment during the 2005-2006 NIS-4 study year. An estimated 12.6 per 1000 white children experienced maltreatment, compared with 24.0 per 1000 black children. The incidence rate for black children was nearly 2 times the rate for white children. The rate for black children was also significantly higher than that for Latino children (14.2 per 1000), with black children 1.7 times more likely to experience maltreatment than Latino children. An estimated 2.6 per 1000 black children were sexually abused, which is nearly 2 times the rate of 1.4 per 1000 white children. The difference between black and white children in their rates of sexual abuse is statistically marginal.

Changes in the incidence rate of abuse were significantly related to race/ethnicity. There was a significant change in overall abuse since the NIS-3 related to the child’s race and ethnicity. The differential decreases were 43% for white children, 27% for Latino children, and 17% for black children.

Sex

Sex-related differences are noted in the reported incidence of sexual abuse. In the NIS-4, a statistically significant difference was noted, with girls experiencing sexual abuse at more than 5 times the rate of boys (3.0 per 1000 girls compared with 0.6 per 1000 boys). The Child Maltreatment 2014 report does not separately report the number of sexual abuse cases by sex, however, it does report that the victimization rates for younger boys (< 1 and 1-5 years) are consistently higher than girls of the same age. At the same time, the victimization rates for older girls (6-10 and 11-17 years) are consistently higher than boys the same age. This is especially true for girls ages 11-17; the victimization rate is 35% higher for girls in this age group. [13] Douglas and Finkelhor have conducted extensive studies on child sexual abuse incidence rate trends and conclude that the overwhelming majority of rigorous studies report a higher incidence of sexual abuse among girls, with females typically representing 78-89% of cases. [16]

Age

Age distribution for child sexual abuse was not reported in a detailed manner in the NIS-4. The Child Maltreatment 2014 report shows that the youngest children are the most vulnerable to all types of maltreatment. In FFY 2014, 27.4% of victims of all types of maltreatment were younger than 3 years of age. Victimization of all types of abuse for children younger than 1 year was 24.4% per 1,000 children in the population of the same age. [13]

Prognosis

For recovery from the emotional trauma associated with child sexual abuse (CSA), prognosis varies depending on a number of abuse-specific and individual and environmental factors. These factors include the following:

-

The child's inherent coping mechanisms and response to trauma and its aftermath

-

Response evident in the child's environment to the victimization

-

Age when the abuse occurred

-

Relationship of the perpetrator to the child

-

Length of time over which the abuse occurred

-

Pattern of the abuse

The response within the caregiving environment to the victimization appears to have an important impact on the ability of the child to work through the difficult issues raised by the sexual abuse.

Looking at children 5 years after presentation for sexual abuse and comparing them to a similarly aged group of children who were not abused, one study found that the children who were sexually abused displayed the following:

-

More disturbed behavior

-

Lower self-esteem

-

Increased tendency for depression

-

Increased tendency for anxiety

Retrospective studies of adults with severe personality disorders characterized by dissociation, impaired interpersonal relationships, and self-mutilation have found a high and significant correlation with histories of sexual abuse.

Prognosis related to any physical injury or infection resulting from the sexual abuse is expected to follow a typical healing course and respond to standard medical interventions.

Paolucci et al's meta-analysis of 37 studies involving 25,367 individuals reported no universal response to child sexual abuse; however, they did confirm that in most cases the experience is negative and that clear evidence proves a link between child sexual abuse and subsequent negative short-term and long-term developmental effects. [24] Paolucci et al conclude that, rather than thinking about a single, specific child sexual abuse response syndrome, the data support a much more complex, multifaceted model of traumatization.

-

Possible factors influencing the decline in substantiated cases of child sexual abuse. Courtesy of David Finkelhor, PhD.

-

Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Pyramid. Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html].

-

Infant girl in frog-leg supine position. Genital examination reveals translucent hymenal membrane with significant redundant tissue making hymenal orifice difficult to appreciate in this photo. With further traction applied to both labia majora, the hymenal orifice could be observed. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

Infant girl in frog-leg supine position. Hymenal orifice is crescentic (little tissue is present at 12-o'clock posterior). Hymen is thin and translucent with vessels visible. Hymenal edge is regular and without interruption. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

Girl in knee-chest position. Hymenal orifice is crescentic, thin, translucent, and without interruption or scarring. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

Infant girl in frog-leg supine position. Hymenal orifice is annular, with tissue present around entire opening. Some redundancy is present. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

Infant girl in frog-leg supine position. Hymenal orifice is annular with a "bump" at 1-o'clock position and a small "notch" at 10-o'clock position. Hymenal membrane is thin and translucent, with no interruption or scarring. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

Girl in frog-leg supine position, exhibiting annular hymenal orifice. Tissue is thin and translucent without disruption or scarring. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

Girl in frog-leg supine position exhibiting hymenal orifice, which is crescentic and has symmetric attenuation at lateral margins. No scarring is present. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

Girl in frog-leg supine position exhibiting hymen. Hymen is septate; a band of tissue crosses the hymenal orifice. Tissue is thin with no scarring present. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

Adolescent girl in supine position demonstrating estrogenized tissue. Hymen is thicker, pink, and fairly opaque with no vessels visible. Tissue is redundant. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

Genital examination of adolescent girl revealing estrogenized hymenal tissue that is pink, thick, and opaque. Orifice appears irregular, secondary to significant redundancy of tissue. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

Genital examination of adolescent girl demonstrating estrogenized hymenal tissue that is pink, thick, and opaque. Orifice is irregular due to areas of redundancy, especially at the 9-o'clock position. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

Prepubertal girl with foul-smelling bloody discharge. On examination, a foreign body in the vagina was found just past the hymenal orifice. The foreign body is lodged in vagina and appears to be toilet tissue that is colonized with bacteria, causing a vulvovaginitis. The foreign body was dislodged with gentle water flushing during examination. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

Genital examination of prepubertal girl with foul-smelling bloody discharge. On examination, a foreign body in the vagina was found lodged just past the hymenal orifice and appears to be toilet tissue that is colonized with bacteria, causing a vulvovaginitis. The foreign body was dislodged with gentle water flushing during examination. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

Infant girl with imperforate hymen and absence of a hymenal orifice. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

Genital examination of girl revealing bruising on medial aspects of labia minora, hymenal trauma with disruption of hymenal tissue, and fresh blood. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

Infant girl with significant bruising that involved labia minora and labia majora, hymenal trauma with disruption of hymen, and fresh blood. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

Genital examination 10 days after infant girl presented with significant bruising that involved labia minora and labia majora, hymenal trauma with disruption of hymen, and fresh blood. Bruising on vulvar structure is nearly resolved. Hymen is healing and no blood is observed. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

Genital examination of girl in frog-leg supine position after genital trauma. Examination reveals suture in place at 6-o'clock position to stop bleeding from injury. Hymenal edge is irregular and asymmetric. Courtesy of Carol D. Berkowitz, MD.

-

US Maltreatment Trends, 1990-2019. Courtesy of David Finkelhor, PhD [Finkelhor D, Saito K, Jones L. Updated Trends in Child Maltreatment, 2019. Crimes Against Children Research Center, University of New Hampshire. February 2021. Online at: http://unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/CV203%20-%20Updated%20trends%202019_ks_df.pdf.].