Practice Essentials

Pectus excavatum, also known as sunken or funnel chest, is a congenital chest wall deformity in which several ribs and the sternum grow abnormally, producing a concave, or caved-in, appearance in the anterior chest wall. The image below illustrates the typical appearance of this deformity in a 16-year-old boy.

A 16-year-old boy with severe pectus excavatum. Note the appearance of the caved-in sternum and lower ribs.

A 16-year-old boy with severe pectus excavatum. Note the appearance of the caved-in sternum and lower ribs.

Pectus excavatum is the most common type of congenital chest wall abnormality (90%), followed by pectus carinatum (5-7%), cleft sternum, pentalogy of Cantrell, asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy, and spondylothoracic dysplasia. Pectus excavatum occurs in an estimated 1 in 300-400 births, with male predominance (male-to-female ratio of 3:1). The condition is typically noticed at birth, and more than 90% of cases are diagnosed within the first year of life. Worsening of the chest’s appearance and the onset of symptoms are usually reported during rapid bone growth in the early teenage years. Many patients are not brought to the attention of a pediatric surgeon until the patient and the family notice such changes. The appearance of the chest can be very disturbing to young teenagers. Problems with self-esteem and body image perception are frequently reported in teenaged patients. Psychologic disturbances are not unusual in older patients.

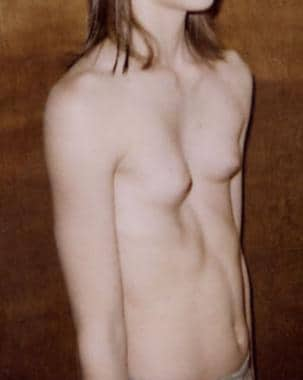

Examples of pectus excavatum in young girls are shown in the images below.

A 10-year-old girl with severe pectus excavatum. In girls, the deformity is of particular concern because of the medial displacement of the breast, resulting in significant asymmetry of the breasts and nipples (cross-eyed appearance of the nipples).

A 10-year-old girl with severe pectus excavatum. In girls, the deformity is of particular concern because of the medial displacement of the breast, resulting in significant asymmetry of the breasts and nipples (cross-eyed appearance of the nipples).

A 10-year-old girl with severe pectus excavatum. Note the significant asymmetry of the breasts and nipples (cross-eyed appearance of the nipples).

A 10-year-old girl with severe pectus excavatum. Note the significant asymmetry of the breasts and nipples (cross-eyed appearance of the nipples).

Pathophysiology

In pectus excavatum, the growth of bone and cartilage in the anterior chest wall is abnormal, typically affecting 4-5 ribs on each side of the sternum. The appearance of the defect widely varies, from mild to very severe cases, and some patients present with significant asymmetry between the right and left sides. The exact mechanism involved in this abnormal bone and cartilage overgrowth is not known, and, to date, no known genetic defect is directly responsible for the development of pectus excavatum. Despite the lack of an identifiable genetic marker, the familial occurrence of pectus deformity is reported in 35% of cases. Moreover, the condition is associated with Marfan syndrome and Poland syndrome.

Etiology

The cause of pectus excavatum is unknown. It probably originates from a genetic defect that results in abnormal musculoskeletal growth. The cartilaginous portion of the rib is very likely the main source of this abnormal growth pattern. Abnormalities of rib morphogenesis and growth are the most likely causes of pectus excavatum and pectus carinatum. In pectus excavatum, the sternum is thought to be pushed in by abnormal growth at the articulation with the ribs and cartilage. Again, the exact mechanism that results in this abnormal growth pattern is not known. Increased work of breathing, as is observed in young patients during exercise or play activity, may contribute to the progression of the pectus deformity, particularly during early the teenage years. However, no scientific evidence supports such a theory.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Pectus excavatum occurs in an estimated 1 in 300-400 births, with male predominance (male-to-female ratio of 3:1). Pectus excavatum comprises approximately 90% of all chest wall deformities.

International statistics

Although limited data are available, international frequency is probably the same as that reported in the United States. However, in certain countries (eg, Argentina), pectus carinatum is more common than pectus excavatum.

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

Pectus excavatum appears to be most prevalent in whites. Unfortunately, no specific data are available regarding racial distribution; however, clinical observation indicates that treating pectus excavatum in African Americans is unusual.

The male-to-female ratio is 3:1. Despite such observation, no known genetic factor linked to the X or Y chromosome has been reported.

Most cases of severe pectus excavatum are noticed at birth, with progressive worsening of the child's growth and development. More than 80% of all cases are identified within the first 1-2 years of life. The condition typically becomes much more pronounced at puberty, during the time of rapid bone and cartilage growth. Most patients are brought to medical attention during their teenage years because of the significant change in the appearance of their chest.

Prognosis

The prognosis of pectus excavatum, with treatment, is excellent. Patients with mild pectus excavatum who do not undergo operative correction also have an excellent prognosis. Patients with moderate-to-severe pectus excavatum may experience problems related to cardiopulmonary impairment, decreased exercise tolerance, decreased stamina, and adjustment disorders related to the impact of this deformity on body image and coping mechanisms. Mortality is not associated with the condition.

A prospective study by Lomholt et al indicated that physical and psychosocial health-related quality of life (HRQL) improves in children following surgery for pectus excavatum. Results were based on patient and parent replies to the Child Health Questionnaire provided preoperatively and at 3 and 6 months following correction of the condition. Increased emotional well-being and self-esteem and greater participation in physical and social activities were reported postoperatively. [1]

A literature review by Maagaard and Heiberg found that patients who underwent correction of pectus excavatum have frequently reported a postoperative increase in exercise stamina, with the outcome apparently unrelated to the specific surgical approach used. The investigators suggested that greater exercise capacity results from an increase in anterior-posterior thoracic dimensions, relieving pressure on the cardiac chambers and, consequently, allowing better filling of the heart. [2]

Morbidity/mortality

Many patients with pectus excavatum are asymptomatic from a functional standpoint. The degree of cardiopulmonary impairment caused by lung compression and the level of cardiac displacement that results from the caved-in chest are subjects of controversy. Exercise tolerance is frequently reported as abnormal, and a restrictive pattern in pulmonary function test can be identified in severe cases. Cardiac function is usually normal, but mitral valve prolapse has been reported in 20-60% of cases. Echocardiography typically reveals some degree of atrial compression and cardiac displacement. Rarely, it may reveal mitral or tricuspid regurgitation. Echocardiographic analysis has demonstrated improved cardiac index upon exertion after operative repair of the deformity. The long-term health risks of patients who are managed without surgery are not known.

Patient Education

Because of the recent advances in the operative repair of pectus excavatum, education of medical professionals and the public is important. Again, patients with pectus excavatum should be referred to a surgeon experienced in the field of congenital chest wall malformations. Early assessment and follow-up is essential to maximize good outcomes.

After operative repair of the pectus excavatum, instruct patients on correct posture to eliminate musculoskeletal pain and to prevent worsening of the spinal deformity. Emphasize that repair of the pectus in itself does not result in correction of any associated spinal deformity or problems related to poor posture.

-

A 16-year-old boy with severe pectus excavatum. Note the appearance of the caved-in sternum and lower ribs.

-

A 10-year-old girl with severe pectus excavatum. In girls, the deformity is of particular concern because of the medial displacement of the breast, resulting in significant asymmetry of the breasts and nipples (cross-eyed appearance of the nipples).

-

A 10-year-old girl with severe pectus excavatum. Note the significant asymmetry of the breasts and nipples (cross-eyed appearance of the nipples).

-

A 12-year-old girl with severe pectus excavatum. Note the significant asymmetry of the breasts. Preoperative photograph.

-

A 12-year-old girl with severe pectus excavatum immediately after minimally invasive repair. Note the immediate correction of the deformity.

-

Preoperative photograph of a 12-year-old boy prior to minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum.

-

A 12-year-old boy 2 weeks after minimally invasive repair of his pectus excavatum. Note the small lateral chest wall incision and the excellent appearance of the anterior chest with 100% correction of the pectus deformity.

-

Preoperative CT scan of the chest of 12-year-old girl with severe pectus excavatum (see Media file 5). Note the severe pectus excavatum with compression of the lung fields and complete displacement of the heart and mediastinal structures to the left hemi-thorax.

-

Illustration showing the minimally invasive technique for correction of pectus excavatum (3) with thoracoscopy (1). Note the long clamp passed from one side to the other (2) grabbing the umbilical tape (4), which serves as a guide for passage of the pectus bar behind the sternum.

-

Operative diagram illustrating the pectus bar after it has been passed behind the sternum (5), under thoracoscopic visualization (1), before turning it over. Note that the concavity of the bar is facing up.

-

Illustration of the pectus bar passed behind the sternum before and after it is turned over. The insert shows the proper technique for fixation of the pectus bar against the lateral chest wall musculature.

-

Illustration of the placement of the third point of fixation for stabilization of the pectus bar. Note that the nonabsorbable suture is placed around the bar and around a rib, lateral to the sternum on the anterior chest wall.

-

Operative diagram illustrating one of the open techniques for correction of pectus excavatum. The drawing is of the so-called "turn-over operation" for repair of pectus. It shows the extensive dissection and the radical nature of this open technique for surgical correction of this congenital chest wall deformity.

-

Operative photograph of the open Ravitch technique for repair of pectus excavatum. The anterior chest is exposed through an anterior thoracic incision and, after raising muscle and skin flaps, each involved cartilage is excised with preservation of the perichondrium. The picture shows one of the cartilages being removed.

-

Operative photograph of the completed Ravitch procedure for correction of pectus excavatum. Note the sternum fractured at 2 different points with a cartilage graft in place to maintain its new position. The involved ribs underwent perichondrial excision. The deformity is completely corrected.

-

Closure of the anterior chest wall incision used for the open type of repair of pectus excavatum (Ravitch operation). Note the drain (small tubing) coming out on the side of the chest. Drains are typically removed after 2-3 days, and they prevent the accumulation of fluid under the skin and muscle flaps created at the time of surgery.

-

Chest radiograph of a 16-year-old patient in which the bar was displaced superiorly and the 2 stabilizers were separated from the Lorenz pectus bar as a result of intense physical activity during soccer practice.

-

Skin rash secondary to a rare case of metal allergy caused by the pectus bar.

-

Recurrent pectus excavatum in a 24-year-old adult patient who underwent open repair using the Ravitch technique at age 10 years.

-

Chest CT scan of the recurrent pectus excavatum in the patient in Media file 20.

-

Recurrent pectus excavatum in young adult female patient who underwent minimally invasive repair at age 8 years.

-

Technique for pectus bar bending. The Lorenz bar is bent by the operating surgeon at the time of pectus bar placement using an instrument known as the "bar bender." A smooth curvature is given to the bar so that it fits under the sternum and corrects the pectus deformity.

-

Pectus bars of various sizes.

-

Technique for removal of the pectus bar. The bar and lateral stabilizer are easily exposed through the old lateral incision in the chest. Once exposed, it is pulled out using a bone-hook instrument.

-

Technique for removal of the pectus bar. The bar is pulled out using a bone-hook instrument.