Practice Essentials

The name rubella is derived from a Latin term meaning "little red." Rubella is generally a benign communicable exanthematous disease. It is caused by rubella virus, which is a member of the Rubivirus genus of the family Togaviridae. Nearly one half of individuals infected with this virus are asymptomatic. Clinical manifestations and severity of illness vary with age. (See the image below.) For instance, infection in younger children is characterized by mild constitutional symptoms, rash, and suboccipital adenopathy; conversely, in older children, adolescents, and adults, rubella may be complicated by arthralgia, arthritis, and thrombocytopenic purpura. Rare cases of rubella encephalitis have also been described in children.

Image in a 4-year-old girl with a 4-day history of low-grade fever, symptoms of an upper respiratory tract infection, and rash. Courtesy of Pamela L. Dyne, MD.

Image in a 4-year-old girl with a 4-day history of low-grade fever, symptoms of an upper respiratory tract infection, and rash. Courtesy of Pamela L. Dyne, MD.

The major complication of rubella is its teratogenic effects when pregnant women contract the disease, especially in the early weeks of gestation. The virus can be transmitted to the fetus through the placenta and is capable of causing serious congenital defects, abortions, and stillbirths. Fortunately, because of the successful immunization program initiated in the United States in 1969, rubella infection and congenital rubella syndrome rarely are seen today.

Pathophysiology

Postnatal rubella

The usual portal of entry of rubella virus is the respiratory epithelium of the nasopharynx. The virus is transmitted via the aerosolized particles from the respiratory tract secretions of infected individuals. The virus attaches to and invades the respiratory epithelium. It then spreads hematogenously (primary viremia) to regional and distant lymphatics and replicates in the reticuloendothelial system. This is followed by a secondary viremia that occurs 6-20 days after infection. During this viremic phase, rubella virus can be recovered from different body sites including lymph nodes, urine, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), conjunctival sac, breast milk, synovial fluid, and lungs. Viremia peaks just before the onset of rash and disappears shortly thereafter. An infected person begins to shed the virus from the nasopharynx 3-8 days after exposure for 6-14 days after onset of the rash.

Congenital rubella syndrome

Fetal infection occurs transplacentally during the maternal viremic phase, but the mechanisms by which rubella virus causes fetal damage are poorly understood. The fetal defects observed in congenital rubella syndrome are likely secondary to vasculitis resulting in tissue necrosis without inflammation. Another possible mechanism is direct viral damage of infected cells. Studies have demonstrated that cells infected with rubella in the early fetal period have reduced mitotic activity. This may be the result of chromosomal breakage or due to production of a protein that inhibits mitosis. Regardless of the mechanism, any injury affecting the fetus in the first trimester (during the phase of organogenesis) results in congenital organ defects.

Etiology

Rubella and congenital rubella syndrome are caused by rubella virus. Only one antigenic type of rubella virus is available, and humans are the only natural hosts. The virus is spherical with a diameter of 50-70 nm, has a central core (ie, nucleocapsid), and is covered externally by a lipid-containing envelope. The nucleocapsid is composed of polypeptide (C protein) and a single-stranded RNA.

Its outer envelope is made up of glycosylated lipoprotein, which contains 2 virus-specific polypeptides (E1, E2) and a host-cell–derived lipid. These 2 envelope proteins comprise the spiked 5-nm to 6-nm surface projections that are observed on the outer membrane of rubella virus and are important for the virulence of the virus.

Monoclonal antibodies directed against epitopes of E1 and E2 have neutralizing activity. Protein E1 is the viral hemagglutinin that binds both hemagglutination-inhibiting and hemolysis-inhibiting antibodies.

Rubella virus is rapidly inactivated by 70% alcohol, ethylene oxide, formalin, ether, acetone, chloroform, free chlorine, deoxycholate, beta-propiolactone, ultraviolet light, extreme pH (< 6.8 or >8.1), heat (>56°C), and cold (from -10°C to -20°C). It is resistant to thimerosal and is stable at temperatures of -60°C or less.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

During the 1962-1965 worldwide epidemic, an estimated 12.5 million rubella cases occurred in the United States, resulting in 20,000 cases of congenital rubella syndrome. Since the licensing of the live attenuated rubella vaccine in the United States in 1969, a substantial increase has been noted in the vaccination coverage among school-aged children and the population immunity. In 2004, the estimated vaccination coverage among school-aged children was about 95%, and the population immunity was about 91%.

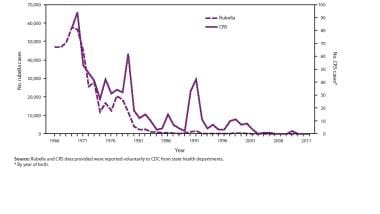

As a result of the progress made in vaccination against rubella, a remarkable drop has occurred in the number of cases of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome. For instance, in 1969, a total of 57,686 cases of rubella and 31 cases of congenital rubella syndrome were recorded. Subsequently, from 1993-2000, the number of cases of rubella recorded annually decreased to a range of 128-364, and cases of congenital rubella syndrome also dropped to 4-9 cases per year. Since 2001, the annual number of rubella cases ranged from a record low of 7 in 2003 to 23 in 2001, and congenital rubella syndrome cases between 0-3 per year. A median of 11 rubella cases was reported in the United States (range: 4–18) each year from 2005 through 2011. Additionally, there were two rubella outbreaks reported involving three cases, as well as four total CRS cases. Twenty-eight (42%) of the 67 rubella cases reported from 2005 through 2011 were known importations. [1] See the images below.

Number of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) cases — United States, 1966–2011. Courtesy of Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

Number of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) cases — United States, 1966–2011. Courtesy of Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

An independent panel convened by the CDC in 2004 to assess progress towards elimination of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome in the United States concluded unanimously that rubella is no longer endemic in the United States. In fact, the pattern of virus genotypes isolated in recent years was consistent with virus originating in other parts of the world. Furthermore, an expert panel reviewed available data and unanimously agreed in December 2011 that rubella elimination has been maintained in the United States. Rubella elimination is defined as the absence of endemic rubella transmission (i.e., continuous transmission lasting ≥12 months). [1]

Following the near record-low levels in rubella incidence in the United States, the occurrence of isolated outbreaks among susceptible adults has also become rare. In fact no outbreak of rubella was reported from 2000-2005, in contrast to the preceding year interval, 1996-1999, when 16 outbreaks were reported. The median number of cases per outbreak was 21. The most recent cases occurred in New York during 1997-1998, Kansas in 1998, Nebraska in 1999, and Arkansas in 1999. Most of these outbreaks were reported in college campuses, military installations, prisons, and workplaces, including health care environments. In most instances, the individuals involved in these outbreaks have no history of rubella immunization. In addition, most of the outbreaks have been reported among persons who emigrated from countries where rubella is not included in the routine immunization schedule.

From 2000 to 2012, rising numbers of WHO member states began using rubella-containing vaccines (RCVs) in their immunization program and began reporting rubella and congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) surveillance data. As of December 2012, 132 (68%) WHO member states had introduced RCV, a 33% increase from 99 member states in 2000. Some 43% of infants had received a RCV dose in 2012, a 96% increase from the 22% of infants who had been vaccinated against rubella in 2000. A total of 94,030 rubella cases were reported to WHO in 2012 from 174 member states, an 86% decrease from the 670,894 cases reported in 2000 from 102 member states. [2, 3]

International statistics

Rubella occurs worldwide. [4] The number of reported cases is high in countries where routine rubella immunization is either not available or was recently introduced. For instance, in Mexico in 1990, a total of 65,591 cases of rubella were reported. After the introduction of rubella vaccine into the childhood immunization schedule in 1998, the number of reported cases declined 68% to 21,173. In Europe, the incidence of rubella remains high. For instance, in 2003, a total of 304,320 cases were reported; 41% of these were from the Russian Federation, and 40% were from Romania.

Although the burden of congenital rubella syndrome is not well characterized in all countries, more than 100,000 cases are estimated to occur each year in developing countries alone. In Europe, a total of 47 cases of congenital rubella syndrome were reported from 2001-2003; 32% were from the Russian Federation, and 36% were from Romania.

In 2020, global rubella vaccine coverage was reported to be 70%, [5] and 43% of countries had eliminated rubella. However, about 100,000 cases of congenital rubella syndrome are estimated to occur each year in low- and middle-income countries. [6]

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

No ethnic difference in incidence has been clearly demonstrated, although the characteristic rash is more difficult to diagnose in persons with dark skin.

No appreciable differences in infection rates by sex are apparent in children, but in adults, more cases are reported in women than in men. Rubella arthralgia and arthritis are more frequent in women than in men.

Before licensing of the live attenuated vaccine in 1969, rubella in the United States was primarily a disease of school-aged children, with a peak incidence in children aged 5-9 years. Following widespread use of rubella vaccine in children, peak incidence has shifted to persons older than 20 years, who comprise 62% of cases of rubella reported in the United States.

Prognosis

The prognosis of postnatal rubella is good with full recovery, while congenital rubella syndrome may have a poor outcome with severe multiple-organ damage.

Morbidity/mortality

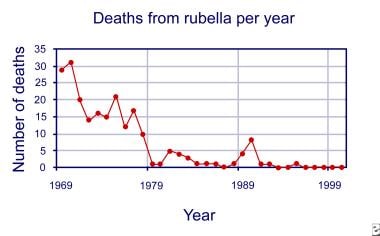

The morbidity and mortality rates of rubella disease dropped remarkably since the licensing of live attenuated rubella vaccine in 1969. In fact, in 1969, complicated rubella infection caused 29 fatalities in the United States, whereas from 1992-2001, only 0-2 deaths per year were recorded (see the image below).

In contrast to postnatal rubella, which is not a debilitating disease, congenital rubella infection may result in growth delay, learning disability, intellectual disability, hearing loss, congenital heart disease, and eye, endocrinologic, and neurologic abnormalities.

Table 1. Reported Cases of Rubella, Deaths From Rubella, and Number of Cases of Congenital Rubella Syndrome in the United States From 1969-2007 [7, 8, 9, 10] (Open Table in a new window)

Year |

Number of Cases |

Number of Deaths |

Cases of Congenital Rubella Syndrome |

1969 |

57,686 |

29 |

31 |

1970 |

56,552 |

31 |

77 |

1971 |

45,086 |

20 |

68 |

1972 |

25,507 |

14 |

42 |

1973 |

27,804 |

16 |

35 |

1974 |

11,917 |

15 |

45 |

1975 |

16,652 |

21 |

30 |

1976 |

12,491 |

12 |

30 |

1977 |

20,395 |

17 |

23 |

1978 |

18,269 |

10 |

30 |

1979 |

11,795 |

1 |

62 |

1980 |

3,904 |

1 |

50 |

1981 |

2,077 |

5 |

19 |

1982 |

2,325 |

4 |

7 |

1983 |

970 |

3 |

22 |

1984 |

752 |

1 |

5 |

1985 |

630 |

1 |

0 |

1986 |

551 |

1 |

5 |

1987 |

306 |

0 |

5 |

1988 |

225 |

1 |

6 |

1989 |

396 |

4 |

3 |

1990 |

1,125 |

8 |

11 |

1991 |

1,401 |

1 |

47 |

1992 |

160 |

1 |

11 |

1993 |

192 |

0 |

5 |

1994 |

227 |

0 |

7 |

1995 |

128 |

1 |

6 |

1996 |

238 |

0 |

4 |

1997 |

181 |

0 |

5 |

1998 |

364 |

0 |

7 |

1999 |

267 |

0 |

9 |

2000 |

176 |

0 |

9 |

2001 |

23 |

2 |

3 |

2002 |

18 |

N/A |

1 |

2003 |

7 |

N/A |

1 |

2004 |

10 |

N/A |

0 |

2005 |

11 |

N/A |

1 |

2006 |

11 |

N/A |

1 |

2007 |

12 |

N/A |

0 |

Complications

Joint involvement

Arthralgia and arthritis are the most common complications of rubella in adolescents and adults. Females are affected 4-5 times more frequently than males. The joints are involved in up to one third of adult women; the fingers, wrists, knees, and ankles are the most frequently involved. Massive effusions often accompany rubella arthritis, and symptoms may persist for 10-14 days. Arthralgia usually begins with the onset of the rash and clears without sequelae within 2-30 days.

Thrombocytopenia

This is a rare complication, occurring in 1 per 3000 cases. Children are affected more frequently than adults, and girls are affected more often than boys. It is self-limited and lasts from a few days to several months.

Neurologic manifestations

Encephalitis is a rare complication and occurs with greater frequency in children. It occurs in 1 per 5000 cases and usually is observed 2-4 days after the onset of rash. In some patients, encephalitis may accompany the rash or be delayed as much as 1 week after onset of the exanthem. CSF examination usually reveals mild pleocytosis (20-100 WBC/mcL) with predominance of lymphocytes. Glucose level is usually normal, while protein levels may be normal or slightly elevated. Rubella encephalitis usually resolves with little or no significant neurologic sequelae.

Mild hepatitis has been a rarely reported complication of acquired rubella.

Patient Education

All pregnant women should avoid any contact with persons infected with rubella.

All susceptible individuals should be immunized.

No special precaution is necessary in the household setting of a child with congenital rubella syndrome, although parents should be counseled regarding potential serious risk to pregnant women exposed to the child.

For excellent patient education resources, visit eMedicineHealth's Children's Health Center and Infections Center. Also, see eMedicineHealth's patient education articles Measles; Skin Rashes in Children; and Immunization Schedule, Children.

-

Number of rubella cases per year.

-

Number of congenital rubella syndrome cases per year.

-

Deaths from rubella per year.

-

Image in a 4-year-old girl with a 4-day history of low-grade fever, symptoms of an upper respiratory tract infection, and rash. Courtesy of Pamela L. Dyne, MD.

-

Number of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) cases — United States, 1966–2011. Courtesy of Centers for Disease Control (CDC).