Overview

Neurofibromatosis (NF) type 1 (NF-1) is a disease characterized by the growth of noncancerous tumors called neurofibromas. These are located on or just underneath the skin, as well as in the brain and peripheral nervous system. They may also form in other body parts, including the eye and orbit.

NF-1 is caused by a mutation in a gene located on chromosome 17. The gene codes for a protein called neurofibromin, which regulates the activity of another protein called ras, involved in cell division. When the NF1 gene is mutated, it may direct the production of a shortened version of the neurofibromin protein that is unable to bind to ras or regulate its activity, resulting in an abnormally active ras protein. Cell division therefore commences but is never instructed to cease, resulting in the formation of the neurofibroma tumors.

In 50% of cases, the individual inherits the mutated gene from a parent in an autosomal dominant pattern. In the other 50% of cases of NF-1, the chromosome 17 mutation is a new one. The NF1 gene is large, making the possibility of mutation relatively high. More than 500 different mutations of the NF1 gene have been found in patients with NF-1. Each child of a parent with NF-1 runs a 50% risk of having the disorder.

The severity and manifestations of NF-1 vary widely among patients with the mutation. Most people with NF-1 have very distinctive café-au-lait spots and freckles, which increase with age. The number and location of other neurofibromas is extremely variable. People who have NF-1 may have very few neurofibromas or they may have thousands of them throughout their body, implicating modifier genes, other than the mutated NF1 gene, as having a role in the disease.

Neurofibromatosis was called von Recklinghausen syndrome for many years, having been first described by Dr. Friedrich von Recklinghausen, a 19th century German pathologist.

Ophthalmologic manifestations of NF-1 include the following:

-

Lisch nodules

-

Plexiform neurofibromas

-

Choroid hamartomas

-

Retinal tumors

-

Optic nerve gliomas

-

Prominent corneal nerves

NF-1 is the most common of the various conditions referred to as hamartomas. Visual loss secondary to optic nerve glioma is the most serious ophthalmologic manifestation of NF-1.

Lisch nodules

Lisch nodules are the most common type of ocular involvement in NF-1. These nodules are melanocytic hamartomas, usually clear yellow to brown, that appear as well-defined, dome-shaped elevations projecting from the surface of the iris. Lisch nodules may be seen without magnification, but a slit lamp examination may be necessary to differentiate them from nevi on the iris, which present as flat or minimally elevated, densely pigmented lesions with blurred margins. The nodules are not thought to cause any ophthalmologic complication.

Lisch nodules are the most common ocular clinical finding in adults older than 20 years with NF-1. Unlike café-au-lait spots, multiple nodules are specific for peripheral NF/NF-1 (see the image below). [1] Lisch nodules are generally absent in central NF/NF-2 and have the following characteristics:

-

Specific for NF-1

-

Smooth, usually bilateral, elevated nodules

-

Usually arise in the first decade; virtually all patients with NF-1 have Lisch nodules by age 20 years

Optic nerve gliomas

An estimated 15-40% of children with NF-1 have optic nerve glioma or visual pathway gliomas involving the optic nerve, chiasm, or optic tract. [2] Some of these lesions are asymptomatic.

Bilateral optic nerve gliomas are almost pathognomonic for NF-1. Unilateral decreased acuity with relative afferent pupillary defect (+/-) and strabismus (+/-) may occur. Optic nerve glioma appears on a computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance image (MRI) as a fusiform dilatation of the optic nerve.

Optic nerve gliomas are locally invasive and slow growing with low malignant potential. However, chiasmatic gliomas may invade the hypothalamus and third ventricle, causing obstructive hydrocephalus. [3] About 10-38% of pediatric patients with optic nerve glioma have NF-1.

In most children with optic glioma, the presenting symptoms may be painless proptosis and decrease in visual acuity. Physical findings include visual loss, loss of color vision, an afferent pupillary defect, and optic nerve pallor or atrophy. A large lesion may compress the optic chiasm, causing nystagmus or other symptoms. Hypothalamic symptoms, such as changes in appetite or sleep, may also occur. Massive lesions may compress the third ventricle, resulting in obstructive hydrocephalus accompanied by headache, nausea, and vomiting.

Plexiform neurofibromas

Plexiform neurofibromas that infiltrate the orbit, temporal region, or eyelids are less common than optic nerve gliomas but are potentially vision threatening. Orbitotemporal neurofibromas can cause strabismus and proptosis and change globe length. In young children, amblyopia may result from obscuration of the visual axis secondary to infiltration and edema of the orbit and eyelids. In a series of 21 children with plexiform neurofibroma of the orbit and temporal areas, 6 patients had only lid involvement and 3 patients had bilateral neurofibromas. Amblyopia secondary to the orbitotemporal plexiform neurofibroma was present in 62%, primarily from ptosis and anisometropia. [4]

The following are characteristics of plexiform neurofibromas of the eyelid:

-

Thickening of upper lid

-

S-shaped deformity

-

"Bag of worms" sensation

Congenital glaucoma ipsilateral to plexiform neurofibromas has been described as a variation of anterior segment developmental disorders.

Choroid hamartomas

Hamartomas of the choroid have the following characteristics:

-

Usually in the posterior pole

-

Flat, ill-defined lesions

-

Contain neuronal and melanocytic components

Retinal tumors

The following are characteristics of retinal tumors:

-

Astrocytic hamartomas (white tumors involving the optic nerve)

-

Combined hamartomas of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium

-

Retinal capillary hemangiomas

-

Possible increase in the incidence of choroidal melanomas

See also Type 1 Neurofibromatosis (NF1), Dermatologic Manifestations of Neurofibromatosis Type 1, Orthopedic Manifestations of Neurofibromatosis Type 1, Genetics of Neurofibromatosis, and Type 2 Neurofibromatosis.

Diagnostic Evaluation

When assessing a patient with suspected ophthalmologic manifestation(s) of neurofibromatosis (NF) type 1, also consider iris nevi, glaucoma, juvenile glaucoma, tuberous sclerosis, and NF-2.

Careful ophthalmologic examination is necessary with periodic follow-up care, and special attention should be directed to optic nerve function to detect previously undiagnosed gliomas of the optic nerve.

No laboratory tests are pertinent in evaluating ophthalmologic manifestations of NF-1. However, tissue biopsy of skin lesions is occasionally necessary to confirm the diagnosis of NF-1.

Histologic Features

Histologic findings of neurofibromas include a typical appearance of markedly enlarged nerves surrounded by thickened perineural structures, which vary depending on their location. As noted previously, Lisch nodules of the iris are histopathologically identical to benign iris nevi.

Histopathologic section of a Lisch nodule showing clump of melanocytes (white arrows) within the stroma of the iris (hematoxylin and eosin, ×100 magnification).

Histopathologic section of a Lisch nodule showing clump of melanocytes (white arrows) within the stroma of the iris (hematoxylin and eosin, ×100 magnification).

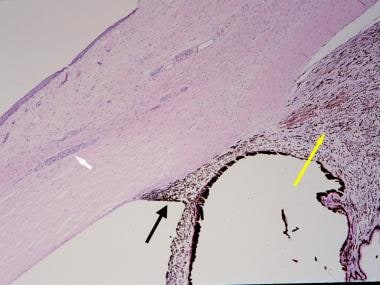

Histopathologic section of an eye from a patient with neurofibromatosis-1 with congenital glaucoma. The white arrow indicates prominent sclerocorneal nerve. The black arrow indicates angle dysgenesis; no trabecular meshwork or Schlemm canal is identifiable. The yellow arrow indicates ciliochoroidal hyperplasia (hematoxylin and eosin, ×40 magnification).

Histopathologic section of an eye from a patient with neurofibromatosis-1 with congenital glaucoma. The white arrow indicates prominent sclerocorneal nerve. The black arrow indicates angle dysgenesis; no trabecular meshwork or Schlemm canal is identifiable. The yellow arrow indicates ciliochoroidal hyperplasia (hematoxylin and eosin, ×40 magnification).

Radiologic Features

Plain film imaging of the long bones can reveal the metaphyseal and the diaphyseal bone defects when present. Lytic lesions of bones due to adjacent neurofibromas can also be detected radiologically.

If optic pathway glioma is suspected, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scanning or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is indicated. Gliomas have a typical fusiform appearance with kinking. MRI can often show greater soft-tissue definition than CT scanning, and it may be particularly useful in detection of intracranial gliomas. [5]

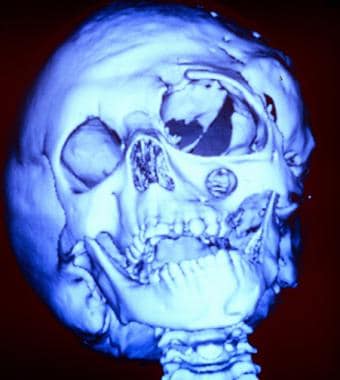

The following are images of a child with severe neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1).

Clinical Management

Treatment of patients with ophthalmologic manifestations of neurofibromatosis (NF) type 1 depends on accurate diagnosis of the specific manifestation. Treatment options should be considered not only to improve survival but also to stabilize visual function. Visual prognosis is related predominantly to the presence or the absence of an optic pathway glioma or congenital glaucoma. [6, 7]

Children with isolated optic nerve tumors have a better prognosis than those with lesions that involve the chiasm or that extend along the visual pathway. Children with NF also have a better prognosis, especially when the tumor is found in asymptomatic patients at the time of screening. Corticosteroids may be prescribed to reduce swelling and inflammation during radiation therapy, or if symptoms return.

The FDA has approved Koselugo (selumetinib) for the treatment of plexiform neuromas associated with NF-1 in children and adolescents aged 2-18 years. Koselugo is a kinase inhibitor that blocks RAS pathway signaling from cell surface receptors to transcription factors by inhibiting MEK, a serine/tyrosine/threonine kinase. The SPRINT Phase II Stratum 1 clinical trial was an open-label, multicenter, single-arm study of 50 pediatric patients with NF-1-related inoperable plexiform neurofibromas (PN) that caused significant morbidity. Thirty-three patients (66%) achieved tumor volume reduction of at least 20%, with 82% of responders having a response duration of greater than 12 months. The drug is given orally at a dosage of 25 mg/square meter of body area, twice dailyt for 28 days. The time of onset of response ranged from 3.3 months to 19.2 months.

Chemotherapy may result in objective tumor shrinkage and will delay the need for radiation therapy in the majority of patients. Chemotherapy may be particularly appropriate for patients with NF and for infants in whom the sequelae of radiation therapy are most likely.

Consultations should include ophthalmologists; they have an important role in diagnosing and treating NF. Other specialists should be consulted as the need arises (eg, neurosurgeons, orthopedists, dermatologists).

Congenital glaucoma

Congenital glaucoma is a challenge to treat in any setting, and NF-1 is no exception. Medical therapy of glaucoma and surgical intervention (goniotomy, trabeculotomy, trabeculectomy, and aqueous shunting devices) may be necessary.

Optic gliomas

Optic gliomas are usually treated with expectant observation, unless aggressive growth is detected by serial imaging studies or progressive deterioration of visual signs and symptoms.

Observation is generally accepted as the appropriate treatment for nonprogressive optic pathway gliomas. Chemotherapy with vincristine and carboplatin is the current standard of care for symptomatic progressive optic pathway gliomas, This treatment has been shown to be more effective in younger, rather than older, children.

Surgery and radiotherapy

Surgical resection of gliomas is ultimately a virtual guarantee of loss of vision. For children with isolated optic nerve lesions and progressive symptoms, complete surgical resection may result in prolonged progression-free survival. [8] Spontaneous regressions have been reported.

Radiation treatment of optic gliomas has been studied extensively with varying results. [9, 10] Radiation therapy results in long-term disease control for most children with chiasmatic and posterior pathway chiasmatic gliomas, but it may also result in substantial intellectual and endocrinologic sequelae and possibly in an increased risk of secondary tumors. Glaser and coworkers found no benefit of radiation therapy for optic gliomas based on analysis of visual fields. [3] Other reports have indicated stabilization or improvement of visual functioning in patients with optic gliomas after radiation therapy. Miller et al reported improvement in survival after radiation therapy in patients with postchiasmatic gliomas. [11]

Relatively recent techniques may minimize side effects while maintaining tumor controlling effect. One such technique creates a computerized 3-dimensional (3-D) image of the brain and glioma and then irradiates the tumor from many directions.

Another promising technique is proton radiation therapy (PRT).

-

Typical appearance of multiple Lisch nodules in a patient with neurofibromatosis-1.

-

Massive facial deformity in a young girl severely affected by neurofibromatosis-1.

-

Three dimensional (3-D) computed tomography (CT) scan of a young girl severely affected by neurofibromatosis-1. This image shows bony deformities of the skull. Note the absence of the greater wing of the sphenoid bone and the enlargement of the infraorbital foramen.

-

Histopathologic section of a Lisch nodule showing clump of melanocytes (white arrows) within the stroma of the iris (hematoxylin and eosin, ×100 magnification).

-

Histopathologic section of an eye from a patient with neurofibromatosis-1 with congenital glaucoma. The white arrow indicates prominent sclerocorneal nerve. The black arrow indicates angle dysgenesis; no trabecular meshwork or Schlemm canal is identifiable. The yellow arrow indicates ciliochoroidal hyperplasia (hematoxylin and eosin, ×40 magnification).