Practice Essentials

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis is an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)–defining infectious disease that can be visually debilitating and that can potentially portend poor systemic outcomes, including early mortality. It is the most common clinical manifestation of CMV end-organ disease and presents as a unilateral disease in two thirds of cases [1] but ultimately is bilateral in most patients in the absence of therapy or immune recovery.

CMV retinitis can arise either upon acute viral introduction to the host or through viral reactivation in the context of immunocompromise.

AIDS is a classic antecedent; however, with the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), CMV retinitis is becoming less common in this setting. Organ transplant recipients and patients who use immunosuppressants are other affected patient populations. Some have felt that retinal inflammation due to CMV among those who were never exposed to HIV is phenotypically different from retinal inflammation in those who were exposed to HIV and developed AIDS to such an extent that they argue for an entirely different nomenclature, including the term chronic retinal necrosis. [2]

CMV retinits can also present in the setting of congenital infection, severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome (SCID), SCID after bone marrow transplanation, AIDS, and after immunosuppressive therapy for various conditions. [3]

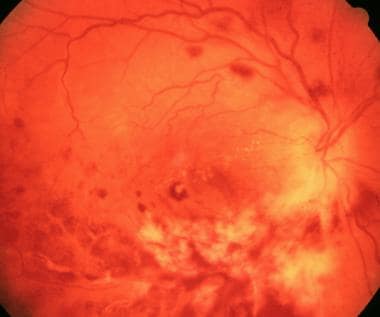

A left-eye wide-field fundus photograph demonstrating a confluent patch of intraretinal whitening, hemorrhage, and vascular attenuation nasal to the optic nerve consistent with CMV retinitis.

A left-eye wide-field fundus photograph demonstrating a confluent patch of intraretinal whitening, hemorrhage, and vascular attenuation nasal to the optic nerve consistent with CMV retinitis.

Signs and symptoms

In most patients, CMV retinitis has an insidious onset that is often asymptomatic, followed by transient visual obscurations ("floaters") and haze, and eventually leading to geographic scotoma and, possibly, complete blindness.

Signs and symptoms of CMV retinitis include the following:

-

Many patients are initially asymptomatic

-

Fulminant hemorrhagic retinal whitening and edema in its acute phase

-

Retinal vascular attenuation and sclerosis

-

Opacification of perivenular retina, also called "frosted branch" angiitis

-

Constitutional symptoms

-

Photopsias ("flashing lights")

-

Transient mobile visual opacities and obscurations within the central and peripheral visual fields ("floaters")

-

Scotoma ("blind spots")

-

Pain and photophobia (uncommon)

Physical examination should be performed to identify the following:

-

Anterior chamber and posterior segment white cell and flare quantification

-

Intraocular pressure measurement

-

Assessment of the severeity of retinitis and location relative to the macula

-

Presence of retinal holes or detachment

Guidelines for evaluation

Diagnosis

No test results are pathognomonic for CMV retinitis. Diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical, laboratory, historical, and imaging information. Examination of the retina by an experienced ophthalmologist is a prerequisite for diagnosis. Blood tests to identify CMV via antigen detection, culture, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have been shown to have poor positive predictive value. A negative plasma or tissue PCR result does not exclude CMV end-organ disease. Available laboratory tests that can support a diagnosis of CMV retinitis include the following:

-

CD4 T-cell count < 50 cells/µL

-

High level of CMV viremia measured via PCR

-

High plasma HIV RNA levels (>100,000 copies/mL)

The following are potentially helpful imaging studies:

-

Fundus photography

-

Fluorescein retinal angiography

-

Optical coherence tomography (OCT)

-

Ophthalmic ultrasonography

-

Anterior chamber tap for Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) testing for CMV

-

Chest radiography

-

Gastrointestinal endoscopy

Treatment

Pharmacotherapy is the mainstay of treatment when retinal detachment is absent. During the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and early 1990s in the United States, intracameral drug-eluting devices (Ganciclovir) were used but have since been discontinued. Current medical options include the following:

-

Ganciclovir, intravenous or intravitreal

-

Valganciclovir, oral

-

Foscarnet, intravenous or intravitreal

-

Cidofovir, intravenous or intravitreal

When retinal detachment has occurred, pars plana vitrectomy with long-acting retinal tamponade is the preferred surgical option. Among available tamponades, silicone oil has been used more frequently, although perfluoropropane has been shown effective. Scleral buckling has not shown equivalent results. [4]

Background

CMV is a beta-group herpesvirus that can cause various manifestations depending on the age and immune status of the host. Latent CMV infects monocytes and their bone marrow progenitors. It can be reactivated when immunity is attenuated. Viral infection is mostly asymptomatic. A mononucleosis-like infection can occur in healthy individuals. In neonates and immunocompromised patients, CMV disease can be devastating. Infected cells, as the name indicates, exhibit gigantism of the entire cell and its nucleus. A characteristic and large inclusion called an "owl's eye" can be found.

The likely mode of CMV transmission varies by age group, as follows:

-

Congenital CVM infection results from transplacental transmission from a mother who does not have protective antibodies.

-

If a child is not infected via transplacental communication, infection can result from cervical or vaginal secretions at birth or, later, through infected human milk.

-

In early childhood, infection can occur through contact with saliva from other children and family members.

-

The dominant mode of transmission in persons aged 15 years or older is venereal. Nevertheless, respiratory secretions and fecal-oral are known reservoirs in this age group. [5]

-

Whole-organ transplantation and blood transfusions can cause iatrogenic CMV infection.

CMV not only takes advantage of suppressed immune surveillance but also induces its own transient and severe immunosuppression. The virus inhibits maturation of dendritic cells and their ability to recruit T cells. Similar to other herpesviruses, CMV can elude immune responses by down-modulating MHC class I and II molecules and producing homologues of TNF receptor, IL-10, and MHC class I molecules.

Individuals with a suppressed immune system are susceptible to serious CMV infections from either a primary event or reactivation of latent CMV. CMV is the most common opportunistic viral pathogen in individuals with AIDS. [6, 7, 8] High viral load and severe deficits in immune function combine to increase the potential for developing CMV retinitis.

When CMV infection causes end-organ nonophthalmic disease, it commonly affects the lung and gastrointestinal system. Necrosis of vital tissues within the lung induces pneumonitis and causes progression to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Intestinal necrosis also leads to pseudomembranes and diarrhea, the end stage of which can be perforation and abdominal infiltration of intraluminal bacteria.

The most common ophthalmic manifestation in its acute phase is retinal necrosis and secondary inflammatory ischemia, whose results are diffuse intraretinal hemorrhage, retinal whitening and edema, vascular attenuation, and sclerosis. [9] The vitreous often demonstrates a haze and cellular infiltration and possibly vitreous hemorrhage. The lesions are coalescent, occur in sequence, and can be multifocal as the disease progresses (see image below). [10] Untreated CMV retinitis inexorably progresses to visual loss and blindness. [11]

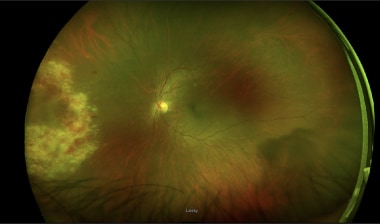

Wide-field fundus photograph showing multifocal intraretinal whitening, hemorrhage, and mild preretinal hemorrhage in a right eye. Within the inferior macula is a vision-threatening lesion.

Wide-field fundus photograph showing multifocal intraretinal whitening, hemorrhage, and mild preretinal hemorrhage in a right eye. Within the inferior macula is a vision-threatening lesion.

Multiple antiviral agents, delivered locally, systemically, or in combination, are currently in use to delay or arrest the progress of the disease. [12] In addition, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) for HIV infection has revolutionized the treatment of CMV retinitis by allowing immune reconstitution in many individuals. [13, 14, 15]

Over a period of 5 years, the incidence of opportunistic infections has decreased, and newly diagnosed cases of CMV retinitis have decreased by as much as 83%. [16]

Pathophysiology

Transmission of CMV occurs through placental transfer, breast milk, saliva, sexually transmitted fluids, blood transfusions, and organ or bone marrow transplants. In the immunocompetent pediatric or adult host, infection generally is asymptomatic or limited to a mononucleosis-like syndrome with signs and symptoms including fever, myalgia, cervical lymphadenopathy, and mild hepatitis.

CMV generally dwells as a latent intracellular virus in immunocompetent children and adults. CMV may reactivate if host immunity is compromised. In immunocompromised individuals, primary infection or reactivation of latent virus can lead to opportunistic infection of multiple organ systems, including the skin (eg, rashes, ulcers, pustules), lungs (eg, interstitial pneumonitis), gastrointestinal tract (eg, colitis, esophagitis), peripheral nerves (eg, radiculopathy, myelopathy), brain (eg, meningoencephalitis), and eye (eg, retinitis, optic neuritis). [17]

In the eye, CMV commonly presents as a viral necrotizing retinitis with vitreitis and may result in retinal detachment. Untreated CMV retinitis inexorably progresses to visual loss and blindness.

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

CMV is ubiquitous, infecting 50-80% of the adult population. Clinically evident disease is found almost exclusively in immunosuppressed individuals. Prior to HAART, CMV occurred in 25-40% of all AIDS patients and was the most common opportunistic infection in AIDS patients with a CD4 count below 50 cells/μL. While HAART has decreased the incidence of CMV retinitis by 55-83%, the decline in AIDS-related mortality has led to an increase in the number of patients with CMV disease.

In a prospective cohort study, Sugar et al estimated the incidence of CMV retinitis in the post-HAART era among 1600 AIDS patients without CMV retinitis at enrollment. They found an incident rate of 0.36/100 person-years, with the highest rate observed among patients with CD4 counts below 50 cells/μL. [18]

Patients with AIDS and CMV are also at risk for cataract, which is likely to be an increasingly important cause of visual morbidity in this population. A study of 489 AIDS patients diagnosed with CMV retinitis found a high prevalence of cataract. Potentially modifiable risk factors identified included large retinal lesion size and use of silicone oil in retinal detachment repair. [19]

CMV retinitis remains a leading cause of visual loss in patients with AIDS and is increasing in organ transplant recipients as the number of those procedures performed each year increases. In a series of 304 recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, CMV retinitis developed in 13 (4%). This represented 23% (13 of 56) of those with significant CMV viremia. [7]

International

The frequency of CMV retinitis in other developed countries is equivalent to that of the United States. The prevalence of CMV retinitis in HIV-infected individuals in developing countries is generally lower than in North America and Western Europe. The lower reported prevalence of CMV retinitis in developing countries, particularly those on the African continent, may be attributed the fact that many HIV-infected individuals die before their immune function deteriorates to the level at which CMV retinitis typically occurs. [20] In general, the incidence of CMV in developing countries reflects the spread of the HIV virus and the availability of antiretroviral medications. [21, 22]

When identified, CMV retinitis often has progressed to the debilitating stage, and intervention is less likely to achieve visual recovery. Improved screening programs and availability of oral valganciclovir are required to improve management of CMV retinitis in this setting. [23]

Sex

Although the incidence of CMV retinitis is the same among men and women, the prevalence is higher in men than in women because of the higher prevalence of AIDS in men. The prevalence of CMV retinitis in the heterosexual community has been steadily increasing.

Age

The age of most individuals who develop CMV retinitis is 20-50 years.

Prognosis

Untreated retinitis will progress to blindness, from retinal necrosis, optic nerve injury, or retinal detachment. [24] Of treated patients, 80-95% will respond, with resolution of intraretinal hemorrhages and white infiltrates (see image below). If treatment is discontinued and the individual is still immunocompromised (ie, CD4 < 50), then the retinitis will recur in 100%. Prior to the advent of HAART, 50% of patients would experience recurrence within 6 months despite maintenance therapy. This rate is reduced if the CD4 count is elevated.

If a retinal detachment occurs, repair with vitrectomy and silicone oil tamponade will result in at least a 70% reattachment rate. [25]

CMV retinitis frequently results in considerable loss of visual acuity, and, without treatment, it almost universally leads to blindness. [26, 27, 28, 29] Early and aggressive treatment with antiviral medication for both CMV and HIV, combined with improved surgical techniques for RD repair, has helped to improve the visual outcomes in these patients.

Untreated CMV leads to progressive visual loss and eventual blindness. Nonfunctioning retina and/or retinal detachment occurs in up to 29% of cases. [30] CMV retinitis causes full-thickness necrosis of the retina.

Retinitis permanently destroys the retina; lesions change appearance with treatment but do not become smaller. Areas of retina affected by retinitis can develop erosive holes despite resolution of the retinitis. If the CD4 count is less than 100 cells/μL, CMV retinitis will develop in 20-30% of patients over a year, although retinitis typically develops if the CD4 count is reduced below 50 cells/μL. Of these patients, 5-10% develop other systemic infections (eg, pneumonitis, colitis, esophagitis).

With the advent of HAART and immune reconstitution, some patients suffer from a relatively new condition known as immune recovery uveitis (IRU). [31, 32, 33] IRU occurs when the poor immune response of an immunocompromised individual is suddenly increased as the patient's restored immune system recognizes and reacts to viral antigens in the retina. This reaction can lead to several complications, including uveitis, leading to hypotony, cataract, and glaucoma; epiretinal membrane (ERM); and cystoid macular edema (CME). [34, 35]

CMV immune recovery retinitis denotes patients who develop active CMV retinitis within 6 months after starting antiretroviral therapy. This may occur despite a CD4 count greater than 50 cells/μL, indicating the need to conduct careful surveillance after initiation of systemic therapy. [36] Despite improvements in systemic treatment for AIDS, the 5-year mortality for those diagnosed with CMV retinitis is 3 deaths per 100 person-years for those with previously diagnosed retinitis and 26.1 deaths per 100 person-years for those with newly diagnosed CMV retinitis. [37]

Patients with newly diagnosed CMV retinitis have a 5-year rate of vision loss to less than 20/40 in 11.8 of 100 eye-years and to 20/200 or worse in 5.1 of 100 eye-years. [37]

Patient Education

Visual symptoms that require a repeat examination are vision loss, development of a visual field defect, new floaters, and photophobia.

Provide education on the following:

-

Medication use and possible adverse effects

-

Education on care of long-term intravenous access site

-

Education on HIV transmission

Patients with CMV retinitis must realize that, despite the possibility of minimal symptoms, debilitating blindness and vision loss can occur with poor compliance to therapy or nontreatment. Even when there is a lesion within the macula, patients still can experience minimal symptoms owing to overlapping visual fields contributed from the contralateral eye and integrated by the central nervous system. Patients may be under the impression that "floaters" are common and insignificant. Coupled with the fact that CMV retinitis is a painless disease, patients may feel less motivation to comply with therapy.

Closely working with an infectious disease specialist and primary care physician should be emphasized, since CMV infection touches on multiple organ systems and requires monitoring of drug toxicities and close communication between specialists. Simultaneous to management of CMV infection, the underlying cause of immune suppression should be addressed, particularly in the form of HAART in patients with HIV infection. Poor adherence to the primary treatment of HIV infection may potentiate viral resistance to common therapies and lead to more advanced disease, even in the presence of standard care.

-

White granular retinitis with intraretinal hemorrhage.

-

Early necrosis at periphery.

-

Attenuation of vessels in area affected by retinitis.

-

Retinitis typically starts in the midperiphery and can progress in a "brush fire" pattern.

-

Progression of retinitis toward the optic nerve.

-

Frosted branch angiitis.

-

Inactive cytomegalovirus retinitis.

-

Cytomegalovirus papillitis.

-

Intranuclear inclusions (arrows) found in cytomegalovirus retinitis. Referred to as owl's eye because of the dark intranuclear inclusion surrounded by a clear halo.

-

Retinal detachment due to peripheral tear in area of necrosis.

-

CMV retinitis with new lesion nasally and older lesion temporally that is starting to pigment.

-

A left-eye wide-field fundus photograph demonstrating a confluent patch of intraretinal whitening, hemorrhage, and vascular attenuation nasal to the optic nerve consistent with CMV retinitis.

-

Wide-field fundus photograph showing multifocal intraretinal whitening, hemorrhage, and mild preretinal hemorrhage in a right eye. Within the inferior macula is a vision-threatening lesion.

-

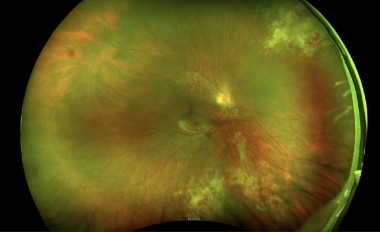

Wide-field fundus photograph illustrating numerous blood vessels within the inferior and nasal periphery that appear attenuated and without flowing blood.