Practice Essentials

Craniopharyngiomas are dysontogenic tumors with benign histology and malignant behavior. [1, 2] These lesions have a tendency to invade surrounding structures and to recur after a seemingly total resection. Craniopharyngiomas most frequently arise in the pituitary stalk and project into the hypothalamus. They extend horizontally along the path of least resistance in various directions.

Signs and symptoms

The time interval between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis usually ranges from 1 to 2 years.

The most common presenting symptoms are headache (55–86%), endocrine dysfunction (66–90%), and visual disturbances (37–68%). Headache is slowly progressive, dull, continuous, and positional; it becomes severe in most patients when endocrine symptoms become obvious.

Diagnosis

The diagnostic evaluation of craniopharyngioma includes high-definition brain imaging. Brain MRI with and without contrast is the gold standard. The use of computed tomography (CT) scan is optional and can show the common calcifications that can be seen in these tumors. However, it is important to note that a CT is not specific enough as a standalone diagnostic test.

Management

Essentially, two main management options are available for craniopharyngiomas: (1) attempt a gross total resection or (2) perform a planned subtotal resection followed by radiotherapy or some other adjuvant therapy.

Agents/modalities used in the treatment of craniopharyngioma include (1) radiation therapy applied as external fractionated radiation, stereotactic radiation, or brachytherapy (intracavitary irradiation) [3, 4, 5, 6, 7] and (2) bleomycin for local intracystic chemotherapy. [8, 9, 10]

Background

Craniopharyngiomas are dysontogenic tumors with benign histology and malignant behavior. [1, 2] These lesions have a tendency to invade surrounding structures and to recur after a seemingly total resection (see the image below). (See Etiology and Treatment.) Craniopharyngiomas are classified as grade I lesions in the most recent WHO classification of tumors with two different tumor types: adantinomatous and papillary. These two entities are now recognized as different tumors and no longer described as subtypes of the same lesion. Their molecular characterization as well as the differences regarding prognosis, imaging, and treatment prompted this separation for their individualized analysis and management. (See Approach Considerations.)

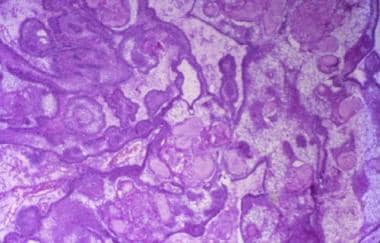

The adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma is a histologically complex epithelial lesion with several very distinctive morphologic features (hematoxylin-eosin, x40).

The adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma is a histologically complex epithelial lesion with several very distinctive morphologic features (hematoxylin-eosin, x40).

Craniopharyngiomas most frequently arise in the pituitary stalk and project into the hypothalamus. They extend horizontally along the path of least resistance in various directions, as follows:

-

Anteriorly - Into the prechiasmatic cistern and subfrontal spaces

-

Posteriorly - Into the prepontine and interpeduncular cisterns, cerebellopontine angle, third ventricle, [11] posterior fossa, and foramen magnum

-

Laterally - Toward the subtemporal spaces

The tumors can even reach the sylvian fissure. In rare cases, the tumors can develop extradurally or extracranially, developing as nasopharyngeal or pure posterior fossa craniopharyngiomas or as craniopharyngiomas extending down the cervical spine. A purely intraventricular craniopharyngioma is usually of the squamous-papillary (metaplastic) type and occurs very rarely.

Craniopharyngiomas usually present as a single large cyst or multiple cysts filled with a turbid, proteinaceous, brownish yellow material that glitters owing to the high content of floating cholesterol crystals. (See Etiology and Workup.)

Clinical behavior and the choice of surgical approach are dictated by the primary location of the tumor and its extension pattern. [12] Prechiasmatic craniopharyngiomas (extending into the subfrontal spaces) and retrochiasmatic craniopharyngiomas (expanding into the posterior fossa) may become large before being diagnosed. (See Presentation and Workup.)

Vascular supply

The vascular supply of the tumor originates from various sources, usually all of which come from the anterior circulation. Small perforators branching from the A1 segment of the anterior cerebral artery supply the anterior portion of the tumor; lateral portions receive perforators from the proximal portion of the posterior communicating artery; and branches of the intracavernous meningohypophyseal arteries supply the intrasellar part. Craniopharyngiomas are rarely supplied with blood coming from the posterior circulation, unless the anterior blood supply for the anterior hypothalamus and floor of the third ventricle is lacking.

Recurrence

Recurrences usually occur at the primary site. Ectopic and metastatic recurrences are extremely rare, but have been reported after surgical removal. The two possible mechanisms of seeding are dissemination of tumor cells along the surgical paths during the procedure and migration of tumor cells through the subarachnoid space or Virchow-Robin spaces, which explains ectopic recurrences distant from the surgical bed and within brain parenchyma.

In one metastatic case, after removal of a suprasellar (adamantinomatous) craniopharyngioma, two peripheral lesions were identified seven years later, adjacent to the dura and contralateral to the initial craniotomy site. They proved to be composed of adamantinomatous tissue, raising the possibility of meningeal seeding.

In another reported case, an adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma recurred at different intervals and at different sites, along the operative track of the initial surgical procedure as well as a distant site within the brain parenchyma, suggesting that both seeding mechanisms were involved in these recurrences.

Etiology

A craniopharyngioma is a slow-growing, extra-axial, epithelial-squamous, calcified, and cystic tumor arising from remnants of the craniopharyngeal duct and/or Rathke cleft and occupying the sellar/suprasellar region. Two main hypotheses—embryogenetic and metaplastic—explain the origin of craniopharyngiomas. These hypotheses complement each other and explain the craniopharyngioma spectrum.

Embryogenetic theory

This theory relates to the development of the adenohypophysis and transformation of the remnant ectoblastic cells of the craniopharyngeal duct and the involuted Rathke pouch. The Rathke pouch and the infundibulum develop during the fourth week of gestation and together form the hypophysis. Both elongate and come in contact during the second month. The infundibulum is a downward invagination of the diencephalon; the Rathke pouch is an upward invagination of the primitive oral cavity (i.e., stomodaeum).

The craniopharyngeal duct is the neck of the pouch, connecting to the stomodaeum, which narrows, closes, and separates the pouch from the primitive oral cavity by the end of the second month. Thus, the pouch becomes a vesicle, which flattens and surrounds the anterior and lateral surfaces of the infundibulum. Walls of this vesicle form different structures of the hypophysis. Finally, this vesicle involutes into a mere cleft and may disappear completely.

The Rathke cleft, together with remnants of the craniopharyngeal duct, can be the site of origin of craniopharyngiomas.

Metaplastic theory

This theory relates to the residual squamous epithelium (derived from the stomodaeum and normally part of the adenohypophysis), which may undergo metaplasia.

Dual theory

This theory explains the craniopharyngioma spectrum, attributing the adamantinomatous type (most prevalent in childhood) to embryonic remnants, and the adult type (most commonly squamous papillary) to metaplastic foci derived from mature cells of the anterior hypophysis. Prevalence of the adult type increases with each decade of life and is almost never found in children.

Other cystic lesions may originate from remnants of the stomodaeum and pharyngohypophyseal duct as well, such as Rathke cleft cysts, epithelial cysts, epidermoid cysts, and dermoid cysts.

Genomic and molecular biology of craniopharyngiomas

Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) studies have been reported with conflicting results. CGH sensitivity is limited to deletions of the order of several mega bases; thus, smaller deletions and balanced alterations can be missed. [13]

Some suggest that chromosomal imbalances [14] do not play a significant role in tumorigenesis of papillary and adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas. Others report a small subset of adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas showing a significant number of genetic alterations and abnormal deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) copy number, thus suggesting a monoclonal origin driven by the activation of oncogenes located at specific chromosomal loci. [15]

Adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas have been consistently reported to show alterations in beta-catenin gene expression. [16, 17, 18] Expression of beta-catenin correlates with some of the hallmarks ("wet" keratin, calcifications, and palisading cells) of adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas. This abnormality has not been reported in papillary craniopharyngiomas.

Beta-catenin is a transcriptional activator of the Wnt signaling pathway and a component of the adherence junction. The Wnt signaling pathway has been proven to play a crucial role in embryogenesis and cancer. Wnt signaling is involved in the determination of cell fate, proliferation, adhesion, migration, polarity, and behavior during development. It also plays an intricate role in the temporal and spatial regulation of organogenesis.

The Wnt complex is made up of three different pathways: canonical, noncanonical, and Wnt/Ca+2. The canonical pathway regulates cell fate determination and primary axis formation through gene transcription. The noncanonical pathway regulates cell movements through modification of the actin cytoskeleton. The Wnt/Ca+2 pathway is involved in regulation of both cell movement and fate determination.

Immunohistochemistry for beta-catenin in adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas showed an abnormal cytoplasmic and nuclear accumulation. The normal membranous staining was present in adamantinomatous and papillary craniopharyngiomas.

Sequencing analysis revealed beta-catenin gene mutations in adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas, while none were found in papillary craniopharyngiomas. All mutations were missense mutations involving the serine/threonine residues at glycogen synthase kinase-3beta (GSK-3beta) phosphorylation sites or an amino acid flanking the first serine residue. These mutations are believed to lead to beta-catenin accumulation as a result of impaired proteosome degradation, this degradation itself being due to ineffective phosphorylation by a mutated GSK-3beta.

Furthermore, the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway has been shown to prevent differentiation (of mouse embryonic stem cells) through convergence on the LIF/Jak-STAT (leukemia inhibitory factor/Janus kinase ̶ signal transducer and activator of transcription) pathway at the level of STAT3. [19] Interferons are known modulators of Jak/STAT pathways, thus revealing the possible molecular basis for interferons as a therapeutic option in adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas.

Some craniopharyngiomas express insulin-like growth factor receptors (IGF-1Rs) and sex hormone receptors (estrogen receptors [ERs] and progesterone receptors [PRs]). [20, 21] Despite reported sporadic expression of IGF-1R in two large, retrospective reviews (including children and adults) in which the mean treatment duration was six years and the mean follow-up period was approximately ten years, no evidence was found to suggest increased recurrence rates in patients who received growth hormone supplementation. [22, 23]

ER and PR expression in one correlative study was linked to higher differentiation and a decreased incidence of tumor recurrence and was proposed as a tool for recurrence risk stratification.

Other markers have been proposed for noninvasive clinical monitoring. Urinary matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs, nonspecific tumor invasion markers) in one case were reported to be a useful predictor of disease activity and risk of recurrence. [24]

Expression of human minichromosome maintenance protein 6 (MCM6) and DNA topoisomerase 2 alpha (DNA Topo 2 alpha) were proposed as histologic markers associated with a higher risk of recurrence in adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas.

Epidemiology

Occurrence

Data from the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS), collected between 2016 and 2020 (corresponding to the 2023 report), [25] found the following results:

-

Overall incidence was 0.19 per 100,000 person years

-

Incidence rates of craniopharyngioma for African Americans exceed those observed for Caucasian, AIAN, and API

-

Distribution by age is bimodal with one peak incidence in childhood (0–19 years) and another in adulthood between the ages of 45 and 84 years with a higher peak for ages 65–74 years

Overall, craniopharyngiomas account for 0.5% of intracranial tumors and 13% of suprasellar tumors. In the United States, the estimated incidence rate per 100,000 per year for the pediatric population (0–14 years) is 0.2, while it is 0.13 for ages 15–39 years. Incidence reaches up to 0.22 for patients older than 40 years.

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

There is an increased incidence in Black patients versus White patients (0.26 vs 0.17 cases per 100,000 people). No differences are seen between Hispanic and non-Hispanic people. A higher five-year total incidence was observed in males compared to females (1102 cases vs 987 cases). [25]

Craniopharyngiomas have a bimodal age distribution pattern, with a peak between ages 5 and 14 years and in adults older than 65 years, although there are reports involving all age groups.

Prognosis

In the United States, data collected for the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB), during the periods of 1985–1988 and 1990–1992, coinciding with the introduction of computed tomography (CT) scanning, indicated that survival rates for craniopharyngioma were 86% at 2 years and 80% at 5 years after diagnosis. According to this past data, survival rate varied by age group, with excellent rates for patients younger than 20 years (99% at 5 years). Survival rate was poor for those older than 65 years (38% at 5 years). Female sex has been reported as an independent predictor of increased cardiovascular, neurologic, and psychosocial morbidity. [26]

According to the latest Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS), for data collected during 2016–2020, survival rates were 92.5% at 1 year and 84.9% at 5 years. These results demonstrate a slight improvement when compared to data from prior decades, as stated above. [25]

-

The adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma is a histologically complex epithelial lesion with several very distinctive morphologic features (hematoxylin-eosin, x40).

-

Adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas. Peripheral palisading of the epithelium is a pronounced feature (hematoxylin-eosin, x100).

-

Adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas. Frequently, the inner epithelium beneath the superficial palisade undergoes hydropic vacuolization and is referred to as the stellate reticulum (hematoxylin-eosin, x100).

-

Adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas. Another distinctive feature of the adamantinomatous variant is scattered nodules of keratin. These nodules are referred to as "wet" keratin because of the plump appearance of the keratinocytes; this is in contrast to the flat, flaky keratin seen in epidermoid and dermoid cysts (hematoxylin-eosin, x100).

-

Adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas. Nodules of "wet" keratin frequently calcify; in aggregate, this calcification often can be detected on CT scans and is a recognized radiologic feature of craniopharyngiomas (hematoxylin-eosin, x100).

-

Papillary craniopharyngioma. In contrast to the adamantinomatous variant, papillary craniopharyngiomas do not show complex heterogeneous architecture but rather are composed of simple squamous epithelium and fibrovascular islands of connective tissue (hematoxylin-eosin, x40).

-

Papillary craniopharyngiomas. Under high power, only simple squamous epithelium is seen in a papillary craniopharyngioma. The distinctive peripheral nuclear palisading, internal stellate reticulum, and nodules of "wet" keratin, which typify the adamantinomatous variant, are not seen in the papillary variant (hematoxylin-eosin, x100).

-

Rosenthal fibers in neuropils surrounding a craniopharyngioma. The brain parenchyma that surrounds both variants of craniopharyngioma is typically gliotic and often shows profuse numbers of eosinophilic Rosenthal fibers. The latter structures are composed of densely compacted bundles of glial filaments and typically are seen in astrocytic cell processes of neuropils that have been subjected to chronic compression from slowly expanding mass lesions. Rosenthal fibers are a characteristic feature of juvenile pilocytic astrocytomas (JPAs), which also may arise in the suprasellar/third ventricular region. Hence, a biopsy that samples only the surrounding neuropil of a craniopharyngioma may yield an erroneous diagnosis of JPA if the pathologist is unaware of the close association of craniopharyngioma with Rosenthal fiber formation (hematoxylin-eosin, x100).

-

T1-weighted MRI with gadolinium in sagittal (A) and coronal (B) views demonstrates the cystic nature of a craniopharyngioma. The calcified component is evident on axial CT imaging (C).

-

T1-weighted MRI with gadolinium reveals a large cystic craniopharyngioma in sagittal (A), axial (B), and coronal (C) views. There is associated elevation of the optic apparatus and displacement of the pituitary stalk.

-

Coronal views of T1-weighted MRI for a patient with craniopharyngioma before gross total resection (A) and at postoperative follow-up evaluation (B). There was no sign of tumor recurrence, and the patient was neurologically and endocrinologically intact.