Practice Essentials

Urethral diverticulum (UD) in females is a localized outpouching of the urethra into the anterior vaginal wall. Most often present in the mid or distal urethra, urethral diverticula typically result from enlargement of obstructed periurethral glands. The rare cases of urethral diverticula reported in males generally have been associated with congenital anomalies or accidental or iatrogenic urethral trauma (eg, urethral catheterization, hypospadias repair). [1, 2] This article focuses on urethral diverticula in females; treatment in males should be individualized and consider patient co-morbidities and any associated pathologic findings. [1]

Although urethral diverticulum is often difficult to diagnose, it has been identified with increasing frequency over the past several decades because of increased physician awareness of the condition. The most common symptoms associated with urethral diverticula include urinary frequency, urgency, and dysuria. In some cases, urethral carcinoma and calculi are also present. Despite the increased awareness, this entity continues to be overlooked during routine evaluation of women with voiding problems. Accurate diagnosis and treatment of urethral diverticula require a high index of suspicion and appropriate radiologic and endoscopic evaluations.

Treatment options for urethral diverticula can range from conservative management to extensive surgery, most commonly diverticulectomy. [3] Patients with pre-existing stress incontinence may receive concomitant autologous pubovaginal sling (APVS) placement at the time of diverticulectomy. [4]

For patient education resources, see Bladder Control Problems.

Background

In 1805, William Hey first described a female with suburethral diverticulum in the medical literature; however, he claimed to have first observed and treated this lesion about 20 years earlier. In the first half of the 20th century only 17 cases were reported, and as a result the condition was assumed to be quite rare. Reports of cases, including a large series from Johns Hopkins Hospital, dating from 1950-1970 have revealed that suburethral diverticula in fact are not rare. Increased awareness of the diagnosis and increased interest in female urology and urogynecology have led to the publication of many reports and review articles in recent years.

In 1875, Lawson Tait was the first to suggest surgical excision as treatment for these lesions. In 1938, Johnson reported on 5 patients treated with complete excision of the diverticular sac. In 1962, Tancer and Hyman described surgical treatment by partial ablation in a small series of 11 patients. In 1970, Spence and Duckett pioneered a marsupialization procedure for distally occurring diverticula. [5] These 3 operations continue to be the mainstays of surgical therapy today.

In 1956, Davis and Cian introduced positive-pressure urethrography, which was a major advance in the diagnostic tools and preoperative evaluation of urethral diverticula. [6] In 1973, Robertson published a landmark article on gynecologic urethroscopy using carbon dioxide gas as a distension media. He described visualization of the diverticular orifice using this technique. [7] Subsequently, ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been added to the diagnostic armamentarium.

Relevant Anatomy

The adult female urethra is approximately 4 cm long and extends from the bladder neck to the external meatus. The mucosa of the female urethra is lined by transitional cell epithelium that gradually changes to nonkeratinizing squamous epithelium from the bladder neck to the external urethral meatus.

Small periurethral secretory glands interdigitate the wall of the urethra to produce lubrication for the inner mucosa. These periurethral glands converge at the distal urethra as Skene glands and empty through 2 small ducts on either side of the external meatus.

Repeated bouts of infection and occlusion of the periurethral glands lead to formation of suburethral cysts. These suburethral cysts enlarge and eventually rupture into the urethral lumen. During urination, constant pooling of urine within these cysts gives rise to urethral diverticula (see image below).

Voiding cystourethrogram reveals contrast pooling in a urethral diverticulum. The urethral diverticulum is located well away from the bladder neck at the distal urethra.

Voiding cystourethrogram reveals contrast pooling in a urethral diverticulum. The urethral diverticulum is located well away from the bladder neck at the distal urethra.

The submucosa of the female urethra is a rich vascular network of spongy tissue. The submucosal layer nourishes the urethral epithelium and the underlying mucous glands. Both the mucosa and the submucosa are responsible for providing a part of the continence mechanism—the mucosal seal.

The mucosal epithelium and the submucosal vascular plexus are highly responsive to estrogen. Loss of estrogen at menopause may result in atrophy or loss of the mucosal seal, causing intrinsic sphincteric deficiency, which is a complex form of stress urinary incontinence.

The urethra contains 2 layers of smooth muscle: the inner longitudinal layer and an outer circular-oblique layer. The inner longitudinal smooth muscle layer is the thicker of the two and continues from the bladder neck to the external meatus. The outer circular-oblique smooth muscle layer encases the longitudinal fibers throughout the length of the urethra. Normally, the inner and the outer smooth muscle layers are adherent via strong connective tissue fibers. The separation of these layers leads to complete urethral prolapse.

The female bladder neck is an internal sphincter but possesses little adrenergic innervation and has limited sphincteric action. The striated urethral sphincter is composed of delicate type I (slow-twitch) and type II (fast-twitch) skeletal muscle fibers surrounded by abundant collagen. It forms a complete ring around the proximal urethra to provide the zone of highest urethral closure pressure. The striated urethral sphincter receives dual somatic innervation from the pudendal and pelvic somatic nerves.

Little sympathetic innervation is found in the female urethra, but parasympathetic cholinergic fibers are found throughout the smooth muscle fibers. Activation of the parasympathetic fibers causes the inner longitudinal smooth muscle of the urethra to contract in synchrony with the detrusor. Contraction of the longitudinal fibers shortens and widens the urethra to allow normal urination.

Pathophysiology

Tubuloalveolar mucous glands, known as periurethral glands, line the urethral wall. They are located posterolaterally in the mid and distal third of the urethra. Most periurethral glands drain into the distal urethra.

When periurethral glands become infected, they may become obstructed. Repeated infections lead to increasing obstruction of the gland and result in periurethral gland enlargement into a suburethral cyst or an abscess cavity. Eventually, the cavity ruptures into the urethral lumen, creating a communication between the urethral lumen and the suburethral cyst. Repeated pooling of urine into the suburethral cyst during urination leads to the formation of a urethral diverticulum.

Urethral diverticula commonly occur in the distal third of the urethra. Although uncommon, distal urethral diverticula may also originate from an obstructed Skene gland. Rarely, urethral diverticula occur in the anterior urethra or its proximal third.

Pathologically, the diverticulum is a urethral evagination that consists of mostly fibrous tissue. Often, an epithelial lining is absent. The chronic inflammation within the diverticulum results in marked fibrosis and adherence of the diverticular wall to the neighboring structures.

Surrounding periurethral fascia often remains intact. However, a severely infected urethral diverticulum may result in spontaneous erosion into the vagina.

Urethral diverticula vary in size, shape, and communication with the urethra. They may be unilocular or multilocular. Some are spherical (see image below), and others are horseshoe shaped. The diverticular opening into the urethral lumen may be very narrow or extremely wide.

Although different types of pathogens have been cultured from the diverticulum, the most commonly identified pathogens include Escherichia coli; Chlamydia species; and, rarely, gonococci.

Etiology

Several theories have been proposed to explain the etiology of female urethral diverticulum. They encompass congenital and acquired causes.

Congenital urethral diverticula are rare; however, urethral diverticula in children have been used to support the congenital origin theory. Congenital urethral diverticula have been postulated to arise from the following:

-

Remnant of Gartner duct

-

Faulty union of primordial folds

-

Cell rests

-

Vaginal wall cysts of müllerian origin

-

Congenital dilatation of periurethral cysts

-

Association with blind-ending ureters

Acquired diverticula may originate from repeated urinary tract infections obstructing the periurethral glands; these can then rupture into the urethral lumen, creating local herniation. Another theory posits that an obstructed periurethral gland becomes infected and develops into an abscess that ruptures into the urethral lumen, forming an ostium. [8]

Epidemiology

Female urethral diverticulum (UD) is a rare disorder with an annual incidence of 17.9 per 1,000,000 (0.02%) per year. [3] UD is thought to represent 1.4% of women with incontinence presenting to urology practices. [9] Urethral diverticula occur most commonly in people aged 30-60 years. The mean age at diagnosis is 45 years. Occurrence in children is rare.

Prognosis

As a consequence of delayed diagnosis, women may encounter several complications, such as recurrent urinary tract infections, stone formation, and more rarely, malignancy. [3]

Although pathology is benign 97% of the time a high degree of suspicion is needed in the case of a firm mass or if MRI indicates a mass within the diverticula. [10] Diverticula frequently contain a thick wall or multiple septa and favor the potential development of adenocarcinoma. In a small series to evaluate the MRI findings differentiating clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra (CCAU) from nonadenocarcinoma of the urethra (NACU) and non–clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra (NCCAU) in women, all six cases of CCAU were associated with a urethral diverticulum. Periurethral or paraurethral glands are located among the inner longitudinal muscles, and it has been postulated that tumors arising from urethral diverticula may dissect the urethral muscle layer. [11]

Surgical excision of the diverticulum continues to be the mainstay of treatment with most studies reporting cure rates of >90%. [9] Complications reported in the literature include the following:

-

Recurrent diverticulum (1-29%)

-

Stress incontinence (1.7-16%)

-

Urethral stricture (0-5%)

-

Recurrent urinary tract infection (0-31%)

Multiple diverticula, proximal diverticula and previous urethral surgery were three independent risk factors for recurrent diverticula. [12]

-

The urethral diverticulum is shown as spherical mass at the distal urethra.

-

Voiding cystourethrogram reveals contrast pooling in a urethral diverticulum. The urethral diverticulum is located well away from the bladder neck at the distal urethra.

-

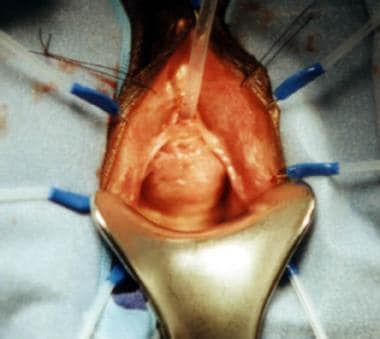

The anterior vaginal wall and the periurethral fascia have been dissected off, exposing the urethral diverticulum.

-

The urethral diverticulum has been excised sharply. Foley catheter is visible through the neck of the diverticulum.

-

The urethral diverticulum is closed in 3 layers with nonoverlapping suture lines. The vaginal wall is closed.