Practice Essentials

Damage to ureters can result from iatrogenic injury or from external trauma, especially penetrating abdominal trauma. [1] Iatrogenic ureteral injury usually involves abdominopelvic surgery or ureteroscopy. Ureteral injuries due to external trauma are rare, as the ureter is well-protected in the retroperitoneum by the bony pelvis, psoas muscle, and vertebrae. Damage to the ureter usually results from a significant traumatic event that is almost always associated with concomitant injury to other abdominal structures. Much of the presentation and management of ureteral injuries are dictated by the severity and management of the associated injuries.

The choice of treatment is based on the location, type, extent, and timing of presentation, as well as the patient's medical history, overall condition, and survival prognosis (see Surgical therapy).

Many novel techniques for ureteral reconstruction after ureteral trauma have been used. Reports of buccal mucosa, appendix, or bowel interposition and biodegradable endoluminal stenting are promising, [2, 3, 4, 5, 6] and such approaches may become a more mainstream method for treating ureteral strictures. Their use in the acute trauma setting has been sparsely reported. [5]

Ureters that have incurred major damage are difficult to reconstruct. The use of tissue engineering techniques for ureter reconstruction and regeneration may be possible in the future. [7]

Background

Ureteral trauma was first reported in 1868 by Alfred Poland, when a 33-year-old woman died 6 days after being pinned between a platform and a railway carriage. At autopsy, the right ureter was avulsed below the renal pelvis. [8] Henry Morris described the first ureteral procedure in 1904, when he performed an ureterectomy on a 30-year-old man who "fell from his van catching one of the wheels across his right loin." [9]

Relevant Anatomy

The ureters are peristaltic tubular structures that course from the kidney to the bladder in the retroperitoneum. Histologically, they are composed of an outer serous layer, a smooth muscle layer, and an inner mucosal layer. The smooth muscle layer consists of 2 circular layers separated by a longitudinal layer.

The ureters can be divided into 3 segments: proximal; middle; and pelvic, or distal. The proximal ureter is the segment that extends from the ureteropelvic junction to the area where the ureter crosses the sacroiliac joint, the middle ureter courses over the bony pelvis and iliac vessels, and the pelvic or distal ureter extends from the iliac vessels to the bladder. The terminal portion of the ureter may be subdivided further into the juxtavesical, intramural, and submucosal portions.

The ureters are at risk during open surgery because of their proximity to many abdominal and pelvic structures. They lie anterior to the psoas muscles and adhere to the posterior peritoneum. The left ureteropelvic junction is posterior to the pancreas and duodenal-jejunal junction. On the right, it lies posterior to the duodenum and just lateral to the inferior vena cava. The left ureter is crossed anteriorly by the inferior mesenteric artery and sigmoidal vessels. The right ureter is crossed by the right colic and ileocolic vessels. As they descend into the pelvis, the ureters course anterior to the iliac vessels but posterior to the gonadal vessels.

In males, the ureter is crossed anteriorly by the medial umbilical ligament. Before entering the bladder, the ureter passes under the vas deferens.

In females, the ureter courses posterior to the ovary, lateral to the infundibulopelvic ligament, and medial to the ovarian vessels. It then passes posterior to the broad ligament and lateral to the uterus. As the ureter approaches the bladder, it is about 2 cm lateral to the cervix. The uterine vessels run just anterior to the ureter near the ureterovesical junction. Most commonly, the ureter is injured in the ovarian fossa near the infundibulopelvic ligament and where the ureter courses posterior to the uterine vessels.

The ureteric arteries course in the adventitia longitudinally along the length of the ureter. They are supplied by branches from the renal, aortic, gonadal, iliac, and vesical arteries. The ureteric arteries are continuous in 80% of cases. In the abdominal portion, the blood supply is derived medially, and, in the pelvis, the blood supply comes from the lateral aspect. The blood supply is richest to the pelvic ureter and is the most limited in the mid ureter in the watershed area between the renal pelvis and the iliac vessels. The blood supply has signficant implications for healing of a ureter undergoing repair or reconstruction.

Lymphatic drainage from the ureter drains to regional lymph nodes. No continuous lymph channels extend from the kidney to the bladder. The regional nodes that serve as drainage include the common iliac, external iliac, and hypogastric lymph nodes.

Etiology

While injuries to the ureter can result from external trauma, iatrogenic causes are more common. These are usually associated with abdominopelvic surgery or ureteroscopy. In addition to intraoperative injury, the ureter can be secondarily affected by postoperative fibrotic or inflammation reactions. Iatrogenic injuries are typically isolated and thus tend to present differently from those associated with external violence.

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma has classified ureter injuries. The following is the ureter injury scale, [10] which includes the grade of injury, type of injury, and description of injury:

-

Grade I – Hematoma; contusion or hematoma without devascularization

-

Grade II – Laceration; less than 50% transection

-

Grade III – Laceration; 50% or greater transection

-

Grade IV – Laceration; complete transection with less than 2 cm of devascularization

-

Grade V – Laceration; avulsion with greater than 2 cm of devascularization

With bilateral involvement, the injury is advanced one grade, up to grade III.

External trauma

Over the past several decades, the percentage of genitourinary injuries caused by external trauma in which the ureter is involved has increased from less than 1% to 2.5%. The increase in incidence may be directly related to an increase in survival of severely injured trauma patients. Increased survival from other more deadly injuries and increased use of imaging allows for diagnosis of ureteric injury. [11, 12]

External trauma can be penetrating (ie, gunshot wounds, stab wounds) or blunt. Interestingly, when all penetrating and blunt traumas were evaluated, the ureter was damaged in less than 4% and 1% of cases, respectively. The type of external trauma also matters; gunshot wounds accounted for 91% of injuries, with stab wounds and blunt trauma accounting for 5% and 4%, respectively. [13]

The relative frequency of ureteral involvement in gunshot trauma is related to the mechanism of the injury. Ballistic injuries affect the ureter in two ways. First, they may directly injure the ureter with varying degrees of severity, ranging from a contusion to complete transection. Secondly, the intramural blood supply of the ureter may be disrupted, resulting in ureteral necrosis. Microvascular studies have shown that this damage may extend as far as 2 cm above and below the point of transection, suggesting that the zone of bullet-associated ureteral injuries extend beyond what is observed grossly. Fortunately, fewer than 3% of gunshot injuries involve the ureters.

Stab wound–related injuries to the ureter are less common than those caused by gunshot injuries. Nevertheless, long-bladed weapons or stab wounds posterior to the midaxillary line should always raise suspicion for possible ureteral involvement.

Blunt trauma can cause ureteral injury from several mechanisms. These mostly involve deceleration or acceleration mechanisms with sufficient force to disrupt the ureter from either the ureteropelvic or ureterovesical junctions. Such injuries can result from a high-speed motor-vehicle collision, a fall from a significant height, or a direct blow to the region of the L2-3 vertebrae.

Iatrogenic causes

Risk factors for ureteral injury during open surgery include any condition with the potential to alter the expected course of the ureter, such as the following:

-

Previous operations

-

Bulky tumors

-

Previous irradiation

-

Inflammatory processes

-

Ureteral duplication

-

Ectopic kidneys

Iatrogenic ureteral injury may result from any of the following:

-

Crushing

-

Suture ligation

-

Devascularization

-

Electrocautery

-

Cryoablation

-

Avulsion

-

Transection

Gynecologic surgery

Abdominal hysterectomy was once the most common cause of iatrogenic ureteral injury (see the image below). However, ureteral injuries can occur during any abdominopelvic surgery.

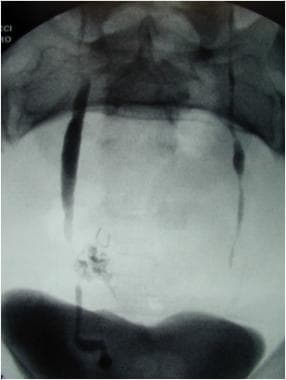

Dual injury during hysterectomy. Combination transection of the right ureter with extravasation and left ureter ligation. Image from combined intraoperative intravenous pyelogram IVP and retrograde pyelogram.

Dual injury during hysterectomy. Combination transection of the right ureter with extravasation and left ureter ligation. Image from combined intraoperative intravenous pyelogram IVP and retrograde pyelogram.

Approximately 52%-82% of surgical ureteral injuries occur during gynecologic procedures. Hysterectomy accounts for most of these cases. However, the modality used plays a role: ureteral injury occurs 1.3%-2.2% of abdominal hysterectomies and in only 1.3% and 0.03% of laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomies, respectively. [14, 15, 16, 17, 18] The risk factors for ureteral injury in these cases include a large uterus, pelvic organ prolapse, and prior pelvic surgery.

The injury typically occurs in the distal ureter in the region of the infundibulopelvic ligament or where a ureter crosses inferior to the uterine artery, often from blind clamping and ligature placement to control hemorrhage. During laparoscopic gynecologic procedures, ureteral injury most commonly results from cauterization or clipping. Interestingly, 33-87% of ureteral injuries caused during laparoscopic surgery are not recognized at the time. [19, 20, 21, 18, 22, 23, 24]

Colorectal surgery

After gynecologic procedures, colorectal surgery is the next most common cause of iatrogenic ureteral injuries. Together, low anterior resection (LAR) and abdominal perineal resection (APR) account for 9% of all such incidences in a combined series and 67% of all general surgical injuries. The incidence of ureteral injury during LAR or APR is 0.3%-5.7% [25] and appears to be rising. [26] The left ureter is involved more commonly than the right, as it may be elevated with the sigmoid mesentery and mistaken for a mesenteric vessel.

Vascular surgery

The overall incidence of ureteral involvement during vascular surgery has been reported as 2%-4%. Ureteral injury may result from direct injury during the procedure or may present as a fistula or hydronephrosis postoperatively. Patients undergoing repeat aortoiliac surgery appear to be at the greatest risk for ureteral injury.

The incidence of asymptomatic hydronephrosis after abdominal vascular surgery has been estimated to be as high as 20%, while only 2% of cases are symptomatic. Of those who are symptomatic, 35% present within 2 months, 50% within 12 months, and 18% after 5 years. [27] Risk factors include ureteral devascularization, retroperitoneal fibrosis, radiation exposure, graft infections, graft dilations, false aneurysms, and anterior graft placement. In patients with early obstruction (< 6 mo), it tends to resolve spontaneously.

Another condition related to vascular surgery is the development of an aortoureteric or graft-ureteric fistula, which can lead to massive hematuria and vascular collapse. The risk factors for the development of the fistulae include anterior graft placement, prolonged use of a ureteral stent, compression, and obstruction.

Urologic procedures

Ureteral injuries that occur during urologic procedures are becoming increasingly common. In one series, they comprised 42% of all iatrogenic injuries. [28] The increased incidence of ureteral injuries during urologic procedures is directly related to the increased use of ureteroscopic equipment. Endoscopic procedures accounted for 79% of injuries, while open surgery accounted for 21%. Most of these injuries occurred in the distal ureter (87%). [28]

The injuries include perforation, stricture, avulsion, false passage, intussusception, and prolapse into the bladder. Risk factors for these injuries include radiation, tumor, inflammation, and impacted stones.

Injury also may be related to the equipment used, such as wires, baskets, and lithotriptors (eg, electrohydraulic lithotriptor [EHL]). Ureteroscopy procedures with ureteral access sheath can also cause ureteral wall injury. [29]

Ureteral injuries during robot-assisted prostatectomies are uncommon. In a series of 6442 consecutivepatients, ureteral injury occurred in three patients [30] .

The increasing use of thermoablation and cryoablation for renal tumors have placed the ureter is at risk for injury. This risk is theoretically higher for lower pole and medially located tumors.

Other iatrogenic causes

Other surgical procedures that may injure the ureters include spinal surgery for disc disease, vaginal surgery for pelvic prolapse, and appendectomy.

Radiation injury to the ureter is rare. The ureter is more resistant to the effects of radiation than the bladder. The incidence of ureteral obstruction due to radiation is 0.04%, while the incidence of obstruction due to recurrent tumor is 95%.

Epidemiology

Most ureteral injuries (75-95%) are iatrogenic and occur during open, laparoscopic, or ureteroscopic procedures. In the setting of trauma, penetrating injuries account for most cases of ureteral injury, and include gunshot wounds, with the ureter being injured in 2–5% of abdominal gunshot injuries. However, due to the life-threatening injuries associated with abdominal trauma, delay in diagnosis is reported in up to 38.2% of the ureteral injuries in these cases, which can result in a significant rate of morbidity and even mortality. [31, 32]

-

Psoas hitch in ureteral trauma.

-

Boari flap procedure in ureteral trauma.

-

Ureteroureterostomy in ureteral trauma.

-

Transureteroureterostomy in ureteral trauma.

-

Complete ureteral replacement utilizing ileum in ureteral trauma.

-

Ileovesical anastomosis. Bladder to the left, ileum to the right.

-

Dual injury during hysterectomy. Combination transection of the right ureter with extravasation and left ureter ligation. Image from combined intraoperative intravenous pyelogram IVP and retrograde pyelogram.