Practice Essentials

Nonbacterial cystitis is a catchall term that encompasses various medical disorders, including infectious and noninfectious cystitis, as well as painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis (PBS/IC). PBS/IC describes a syndrome of pain and genitourinary symptoms (eg, frequency, urgency, pain, dysuria, nocturia) for which no etiology can be found. There are many controversies regarding nonbacterial cystitis, including possible etiologic agents, methods of diagnosis, and treatment, especially for noninfectious causes.

Infectious nonbacterial cystitis includes the following forms of the disease:

-

Viral

-

Mycobacterial

-

Chlamydial

-

Fungal

-

Schistosomal

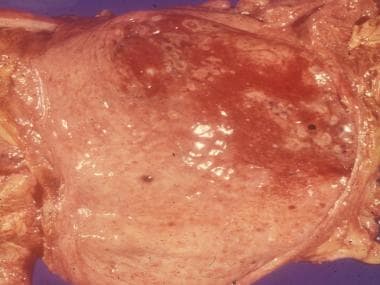

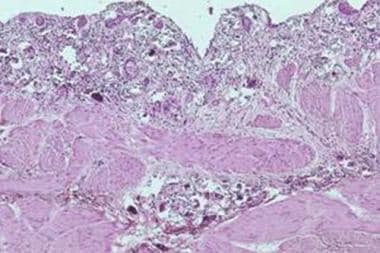

Candidal infection of the bladder is shown in the image below.

Noninfectious nonbacterial cystitis includes the following forms of the disease:

-

Chemical

-

Autoimmune

-

Hypersensitivity

General symptoms of cystitis include urgency, frequency, dysuria, and, occasionally, hematuria, dyspareunia, abdominal cramps, and/or bladder pain and spasms. Establishing or excluding a specific diagnosis often requires repeated cultures and various urologic procedures, including cystoscopy with bladder biopsies, various bladder tests, and immune system function examinations. Some conditions, such as carcinoma in situ, bladder calculi, and urethral foreign bodies, may result in symptoms that mimic those of nonbacterial cystitis.

While originally non-infectious or nonbacterial cystitis was reported more frequently in women, in the last decade there is increased reporting of similar syndromes in men. [1] In a twin registry where one member of the pair experienced symptoms of chronic fatigue for at least 6 months, the chronically fatigued twin had a significantly higher incidence of chronic pelvic pain (women) and chronic nonbacterial prostatitis (men). [2]

Anatomy

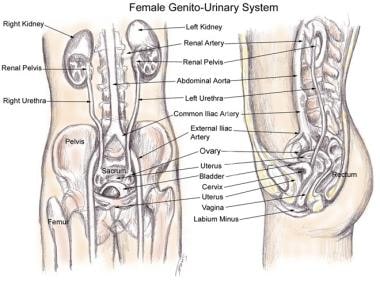

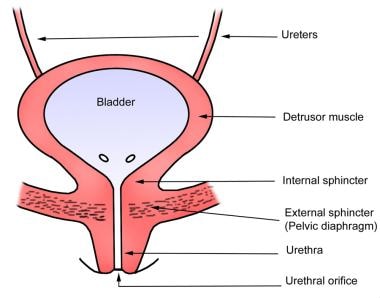

The images below demonstrate the anatomy of the female pelvis, the gross anatomy of the bladder, and the muscles of the pelvic floor that may be involved in nonbacterial cystitis.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of the disorder depends on its etiology.

Advances in understanding the pathophysiology of complex pain syndromes have demonstrated growth of bridging neurons in the dorsal horns of the spinal cord between the type C pain fibers and the type A pain fibers, indicating perception of pain started by stimulus that is usually nonpainful.

Another example of neural cross-talk is an experiment in rats that demonstrated increased muscle spasm in the bladder with colonic irritation and in the colon with bladder irritation. This may help to explain the concomitant occurrences of irritable bowel syndrome, pelvic pain syndrome, and interstitial cystitis. [3]

Infectious cystitis

Viruses

Cytopathologic viruses, such as herpes simplex virus–1 (HSV-1) and HSV-2, live integrated into the host genome in the nervous system. Impairment of immune surveillance, which can be caused by comorbid diseases, drugs, or chronic activation of the neuroendocrine pathways involved with corticosteroid production, allow the virus to activate, travel down the peripheral nerves, and cause an outbreak of the disease. Viruses normally do not cause cystitis in immunocompetent adults. In a given patient, however, whether the infection is due to primary infection or reactivation of latent virus is unclear.

Chlamydia

Chlamydiae are obligate intracellular parasites with a unique reproductive cycle that involves 2 forms: (1) an extracellular form adapted to survival in the environment, which allows the infection to be transmitted from one person to another, and (2) an intracellular form that replicates and produces more extracellular forms. Chlamydia trachomatis is the organism most commonly identified; in addition to cystitis, it can cause the following disorders:

-

Urethritis

-

Cervicitis

-

Pelvic inflammatory disease

-

Proctitis

-

Epididymitis

Mycobacteria

Initial infection with mycobacteria generally elicits a mild inflammatory response with few or no symptoms. Weeks after the primary infection, with continued replication of the bacilli, development of cell-mediated immunity leads to macrophage infiltration and ingestion of the pathogen.

While mycobacteria can persist within macrophages, replication usually ceases, and spread of the disease is contained. Individuals with disturbances in cell-mediated immune responses are therefore at higher risk for dissemination of the infection.

Other infections

Fungal infections can occur in immunocompetent hosts, but they are more likely to occur in individuals with abnormal immune systems. Species of fungi associated with urogenital fungal infections include Blastomyces dermatitidis, Candida species, and Torulopsis glabrata.

Schistosomiasis can cause symptoms of cystitis, including frequency, urgency, and dysuria. Schistosoma eggs are deposited within the bladder wall as part of their life cycle. An eosinophilic immune reaction is generated in response to the eggs, leading to chronic inflammation. Chronic schistosomiasis can eventually result in small bladder capacity, obstructive uropathy, and bladder cancer.

Noninfectious cystitis

Radiation cystitis is presumably due to the ionizing radiation administered for treatment for pelvic and urogenital cancers. In a study by Perez et al, [4] the volume of space irradiated and the total dose of radiation were important factors that influenced morbidity. Patients treated with stationary radiation portals that delivered higher doses of radiation to the bladder had a significantly higher incidence of morbidity than did patients treated with rotating portals (18% vs 5%, respectively).

Eosinophilic cystitis has been associated with various etiologic factors, such as allergies, bladder tumors, and parasitic infections, which stimulate antigen formation, leading to antigen-antibody complexes that stimulate inflammatory cascades. This, in turn, leads to eosinophil infiltration and chemokine release, causing fibrosis. [5]

Chemical cystitis, which is due to chemotherapy with alkylating agents such as cyclophosphamide, is thought to be due to metabolites excreted in the urine. The effects appear to be related to the dose and duration of therapy.

Etiology

Infectious etiologies

Viruses normally do not cause cystitis in immunocompetent adults. Improved molecular detection techniques have allowed the recognition of viral infections, such as the following, in immunocompromised patients:

-

Adenovirus infections [10]

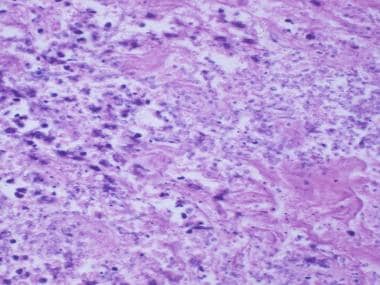

Herpes and chlamydial cystitis are sexually transmitted, while other types, such as fungal cystitis, occur mainly in immunocompromised hosts. [11, 12] Corynebacterium urealyticum has been associated with a very rare chronic inflammatory disorder, encrusted cystitis, which is characterized by precipitation and encrustation of phosphate ammonium magnesium salts on the bladder mucosa. [13] Yeast infiltration of the bladder is shown in the image below.

Schistosomiasis (shown in the image below) can cause severe cystitis and lower urinary tract symptoms, due to an inflammatory reaction to Schistosoma eggs embedded in the host's bladder.

Noninfectious etiologies

Cystitis may occur following radiation therapy to the pelvis for cancer treatment. The average time from the beginning of radiation therapy to initial symptoms can be several months to several years. Symptoms can include anything from mild bleeding to severe, recurrent bleeding and pain requiring hospitalization for treatment.

Autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or Sjögren syndrome can also be associated with irritative bladder symptoms, such as frequency or pain. Eosinophilic cystitis is a rare pathologic condition characterized by transmural inflammation of the bladder predominantly by eosinophils and fibrosis, with or without muscle necrosis. [5]

Cystitis may also be caused by chemicals and medications. Cyclophosphamide, used to treat malignancies and vasculitides (eg, SLE, granulomatosis with polyangiitis [Wegener granulomatosis]) can cause hemorrhagic cystitis. [14] Low-dose methotrexate used to treat rheumatoid arthritis has also been reported to cause hemorrhagic cystitis. [15] Rare cases of very severe and refractory interstitial cystitis have been reported in patients with SLE receiving treatment with methotrexate. [16]

Reports have documented cystitis arising after the recreational abuse of the anesthetic agent ketamine. [17, 18] The severity of lower urinary tract symptoms increases with the duration of ketamine abuse, and may be exacerbated by the combined use of ketamine and other substances (eg, marijuana, MDMA [ecstasy]). [19]

Epidemiology

Infectious cystitis

The frequency of viral and herpetic cystitis is unclear because culture results can be falsely negative. For example, it has been proposed that both HSV-1 and HSV-2 may initially cause asymptomatic infections, so the incidence of herpetic cystitis may be higher than culture-positive results indicate.

Hemorrhagic cystitis (HC) due to adenoviral infections is common in immunocompromised hosts, especially bone marrow transplant recipients or those with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Hemorrhagic cystitis due to infection with adenoviruses or BK polyomavirus has been reported in 20% and 8% of pediatric bone marrow transplant patients, respectively.

The frequency of BKV-associated HC in hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients is about 10%. [6]

The frequency of chlamydial genitourinary infections may also be higher than cultures indicate. A study of 130 patients aged 14-25 years in an urban outpatient clinic demonstrated a 21% frequency of C trachomatis infection; one third were asymptomatic. Risk factors for Chlamydia infection in this group included younger age, more than one sexual partner, and international travel. In another study, of 36 cases of bladder biopsies performed to evaluate cystitis, antigen from C trachomatis was detected by immunochemistry in one third of the specimens.

Mycobacterial cystitis or urogenital tuberculosis is more common in underdeveloped countries and continues to be a major urologic problem in places such as North Africa, mainly because of diagnosis delays. The tuberculosis vaccine, bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), which may be instilled into the bladder to treat bladder tumors, has also been reported to cause cystitis.

Fungal cystitis, most commonly due to Candida species, [20] is more common in immunocompromised hosts, such as those with diabetes mellitus, those who have received chemotherapy, older subjects, women, and those with indwelling catheters who have received multiple courses of antibiotics.

Candida represented 55% of pathogens responsible for ICU-acquired positive urine cultures in a study of 406 ICU patients. Illness severity was identified as a risk factor for candiduria in the study population. [21]

Schistosomiasis most frequently occurs in the developing world, although it is estimated that 400,000 cases exist in the United States. There are five different species of schistosomes; Schistosoma haematobium often causes urinary tract infections. [22]

Noninfectious cystitis

Radiation cystitis was reported to occur in 6.5% of 1784 patients treated with a combination of external beam and intracavitary radiotherapy for stage Ib carcinoma of the cervix. Perez et al reported moderate-to-severe cystitis occurring in 12% of 738 patients treated with definitive irradiation therapy for prostate cancer after 10 years. [4]

Autoimmune disease related to cystitis is another entity that may be more common than previously realized. A review in Sweden demonstrated that 17% of all patients diagnosed with interstitial cystitis had rheumatoid arthritis, 47% had hypersensitivity reactions or allergies, and 2.3% had either ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease, a rate more than 30 times the prevalence rate in the general population.

Both Sjögren syndrome and SLE have been associated with urinary symptoms. In one study by Haarala et al of 121 patients with Sjögren syndrome or SLE and 121 age- and sex-matched controls, more than 60% of patients had some urinary symptoms, compared with 20% of controls. [23] Case reports describe a form of interstitial cystitis termed lupus cystitis, occurring in 0.5–2.3% of patients with SLE; reported cases come predominantly from East Asia. However, a study from Colombia of a cohort of 240 patients with SLE reported that 5% had findings consistent with lupus cystitis at some point in their disease course. [16]

Approximately 30% of long-term ketamine abusers experience ketamine-induced cystitis (KC). The incidenc of KC has risen in recent years in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia, and in some European countries. However, the actual prevalence of KC is unknown. [24]

Prognosis

Infectious etiologies

Infectious causes of nonbacterial cystitis, such as HSV-1 or HSV-2, can be treated; however, the treatment does not eliminate the dormant virus integrated into the host genome, so the disease can recur.

Both chlamydial and mycobacterial infections can be cured. For chlamydial disease, cure is not protective and the disease can be reacquired. In addition, while mycobacterial infections can generally be cured with regimens containing 3 or 4 drugs, a review by Mnif et al of 60 cases of urogenital tuberculosis found that only 2 were cured by medical therapy alone. [25] Of the remaining patients, 54 required one of the following surgical interventions:

-

Nephrectomy (43 patients)

-

Ureterovesical reimplantation (7)

-

Augmentation enterocystoplasty (11)

-

Other ureteral diversions (5)

Two patients whose medical status and nutritional status were poor to begin with died despite aggressive therapy.

Fungal infections are usually curable, depending on the underlying health status of the patient. Because patients with severe immunosuppression (eg, those with untreatable malignancies, AIDS, poorly controlled diabetes, transplant recipients) are the ones most likely to develop these infections, some patients may require continued treatment to ensure that the infection does not recur.

Noninfectious etiologies

Radiation cystitis, when it does occur, is usually mild and does not require specific therapy. [26] However, the incidence of bleeding, scarring, and/or obstruction increases over time, and symptoms may occur for the first time many years after the radiation treatment. Some patients with heavy bleeding, strictures, or obstruction may require urinary diversion surgery for symptom relief. [27]

Chemical cystitis due to chemotherapy agents is generally mild, with no long-term consequences, and resolves when the medications are stopped. No known cures exist for autoimmune disease–associated cystitis, but symptoms can often be controlled with anti-inflammatory agents or corticosteroids. Eosinophilic cystitis often recurs despite resection of the lesion and anti-inflammatory treatments, so long-term follow-up is required. [5]

Ketamine-induced cystitis improves in most patients after cessation of ketamine use. Recurrent UTI and symptom relapse occur in patients who reuse ketamine after treatment. Patients who continue to abuse ketamine or with longer duration of ketamine abuse may develop intractable bladder pain that is refractory to treatment. Patients with chronic vesicoureteral reflux and/or hydronephrosis may develop irreversible renal function impairment. [24]

-

Gross pathology of the bladder with candidal infection and hemorrhage.

-

Gross anatomy of the female pelvis.

-

Gross anatomy of the bladder.

-

Female perineal anatomy. The urogenital diaphragm and levator ani muscles have been removed, revealing the internal pudendal nerves and vessels, the rectum, and the posterior vaginal wall.

-

Schistosomiasis of the ureter.

-

Infiltration of yeast in the bladder wall.