Practice Essentials

The normal functioning ovary produces a follicular cyst 6-7 times each year. In most cases, these functional cysts are self-limiting and resolve within the duration of a normal menstrual cycle. In rare situations, a cyst persists longer or becomes enlarged. At this point, it represents a pathological adnexal mass.

Adnexal masses present a diagnostic dilemma; the differential diagnosis is extensive, and most masses are benign. [1, 2, 3] However, without histopathologic tissue diagnosis, a definitive diagnosis is generally precluded. Physicians must evaluate the likelihood of a concerning pathologic process using clinical and radiologic information and balance the risk of surgical intervention for a benign versus malignant process.

Since ovaries produce physiologic cysts in menstruating women, the likelihood of a benign process is higher in women of reproductive age. In contrast, the presence of an adnexal mass in prepubertal girls and postmenopausal women heightens the risk of a malignant neoplastic etiology.

History of the Procedure

In the past, physicians relied on the findings of a pelvic examination to diagnose an adnexal mass. With the introduction of imaging modalities including transabdominal and vaginal ultrasonography, [4] Doppler color scans, and MRI, more characterization of the internal structure of the mass (ie, wall complexity, mass contents) is possible. [5, 6, 7, 8] Although not definitive, these findings can help determine whether a mass appears more consistent with a physiologic cyst or neoplastic process.

Problem

The following masses pose the greatest concern:

-

Those that have a complex internal structure

-

Those that have solid components

-

Those that are associated with pain

-

Masses in prepubescent or postmenopausal women

-

Large cysts (A variety of cut-off sizes have been proposed. In some institutions, unilocular cysts up to 10 cm have been followed conservatively, even in postmenopausal women. [8] However, the presence of complex cysts in postmenopausal women generally heightens suspicion, regardless of size.)

-

In menstruating women, those who persist beyond the length of a normal menstrual cycle without typical characteristics of a benign process such as a hemorrhagic cyst

Epidemiology

Determining the true frequency of adnexal masses is impossible because most adnexal cysts develop and resolve without clinical detection. When assessing the clinical significance of an adnexal mass, consideration of several age groups is important.

In girls younger than 9 years, 80% of ovarian masses are malignant and are generally germ cell tumors. [9, 10] During adolescence, 50% of adnexal neoplasms are mature cystic teratomas (often known as dermoid cysts). Women with gonads that contain a Y chromosome have a 25% chance of developing a malignant neoplasm (most commonly a dysgerminoma). Endometriosis is uncommon in adolescent women but may be present in as many as 50% of those who present with a painful mass. In sexually active adolescents, one must always consider a tubo-ovarian abscess as the cause of an adnexal mass. [11, 12]

In women of reproductive age who have had adnexal masses removed surgically, most are benign cysts or masses. Ten percent of masses are malignant [13] ; though in patients younger than 30 years many are of low malignant potential. Thirty-three percent are mature cystic teratomas, and 25% are endometriomas. The rest are serous or mucinous cystadenomas or functional cysts.

Historically, postmenopausal women with clinically detectable ovaries were thought to be at great risk of having a malignant neoplasm. With the increasing prevalence of radiologic testing, many smaller, simple cystic masses have been identified; therefore, the risk of malignancy may be only 20-30%. The differential diagnosis includes benign cysts; metastatic versus primary ovarian malignancies; tubal cysts; and neoplasms such as paratubal cysts, hydrosalpinx, or, rarely, fallopian tube cancer. Radiologic testing allows the architecture of the mass to be evaluated, which decreases the need to operate on benign masses in this age group.

Overall, approximately 10% of ovarian cancers are hereditary. As such, patients with a history suggestive of a hereditary breast-ovarian cancer syndrome (BRCA1 or BRCA2) or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome (HNPCC or Lynch syndrome) are at increased risk for developing a malignant mass. [14] The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act mandates that genetic counseling and testing for BRCA mutations be covered as a preventative service in high-risk individuals. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Society for Gynecologic Oncology, American Society of Breast Surgeons, and American College of Medical Genetics each have distinct criteria for referral to genetic counseling. [15, 16, 17] All include women with high-grade serous ovarian cancer, primary peritoneal cancer, or fallopian tube cancer at any age, as recent data suggest that as many as 16-21% of these women have a germline mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2. [18, 19, 20]

In all age groups, the physician must also consider the possibility of uterine masses or structural deformities. Pregnancy-related adnexal masses, including ectopic pregnancy, theca lutein cysts, corpus luteum cysts, and luteomas, must be considered in all premenopausal women. [21, 22]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology is not well understood for most adnexal masses; however, some theories have been proposed. Functional cysts may be the result of variation in normal follicle formation. Mature cystic teratoma may be the result of abnormal germ cell proliferation. Endometriomas are thought to result from retrograde menstruation or coelomic metaplasia. The exact cause of epithelial neoplasms is unknown, but recent studies have suggested a complex series of molecular genetic changes is involved.

Presentation

The clinical presentation of an adnexal mass can be variable, but patients are often asymptomatic. Patients may present with masses that are found (1) at the time of a pelvic examination, (2) at the time of a radiologic examination for another diagnosis, or (3) at the time of a surgical procedure. Women who have symptoms may note urinary frequency, pelvic or abdominal pressure, and bowel habit changes due to the mass effect on these organs. Girls younger than 10 years frequently present with pain, as do older women who have infected masses or endometriosis. Adnexal torsion classically presents with acute abdominal pain, requiring urgent surgical intervention.

As the adnexa are located deep in the pelvis, masses may be palpated with a standard gynecologic examination. Findings such as size greater than 10 cm, nodularity, irregular adnexal contour, or fixed position are suggestive of malignancy. However, other factors, such as obesity and size of mass, may limit the accuracy of physical examination. [23]

Since many patients with adnexal masses are asymptomatic, there has been extensive research into effective screening strategies for ovarian cancer. The most widely studied potential screening test is the serum measurement of cancer antigen 125 (CA-125). CA-125 is expressed by tissues derived from coelomic and müllerian epithelia, and levels are elevated in at least 80% of females with advanced epithelial ovarian cancers. However, single-point CA-125 measurements are limited by both a lack of sensitivity (low in early-stage malignancy) and specificity (it is produced by many other nonmalignant conditions).

The largest screening trial performed to date (The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Randomized Controlled Trial, or PLCO Trial) found that among the general population, screening with CA-125 and transvaginal ultrasound versus usual care did not decrease ovarian cancer mortality. The study also reported serious complications arising from diagnostic interventions performed to evaluate false-positive screening results. [24]

While many other screening algorithms are being actively investigated, at this time there is insufficient evidence to support the routine use of pelvic ultrasound and/or CA-125 to screen for ovarian cancer in the general population. As with all screening tests, the ideal screening algorithm will ultimately balance the accurate detection of ovarian malignancy at an early stage while minimizing unnecessary interventions in patients.

Indications

Most adnexal masses resolve spontaneously over time; therefore, care must be taken to not overreact to such a finding. For example, in the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis Phase 5 (IOTA5) study, the incidence of spontaneous resolution within 2 years of follow-up among patients with an adnexal mass with benign ultrasound morphology was 20.2%. [25] Surgeons who rush women with small, asymptomatic masses into surgery often create more pathology than they cure. Any surgery performed on adnexal structures can result in impaired fertility.

On the other hand, these same asymptomatic masses can be early ovarian cancers that require immediate attention. The use of radiologic testing often helps determine which women require attention (see Imaging Studies). Serum testing of CA-125 can be used in combination with radiologic testing to stratify the risk of adnexal masses. However, it is important to recognize the limitations of this serum marker. A large Swedish study has shown that approximately 50% of women with stage I ovarian cancer have a normal CA-125 test value. In addition, a high false-positive rate can be caused by pregnancy, endometriosis, cirrhosis, and pelvic or other intra-abdominal infections. [26, 27, 28] CA-125 screening does not add useful information for specific diagnosis of benign adnexal tumors except for endometrioma. An elevated level significantly increases the probability of such a lesion. [29]

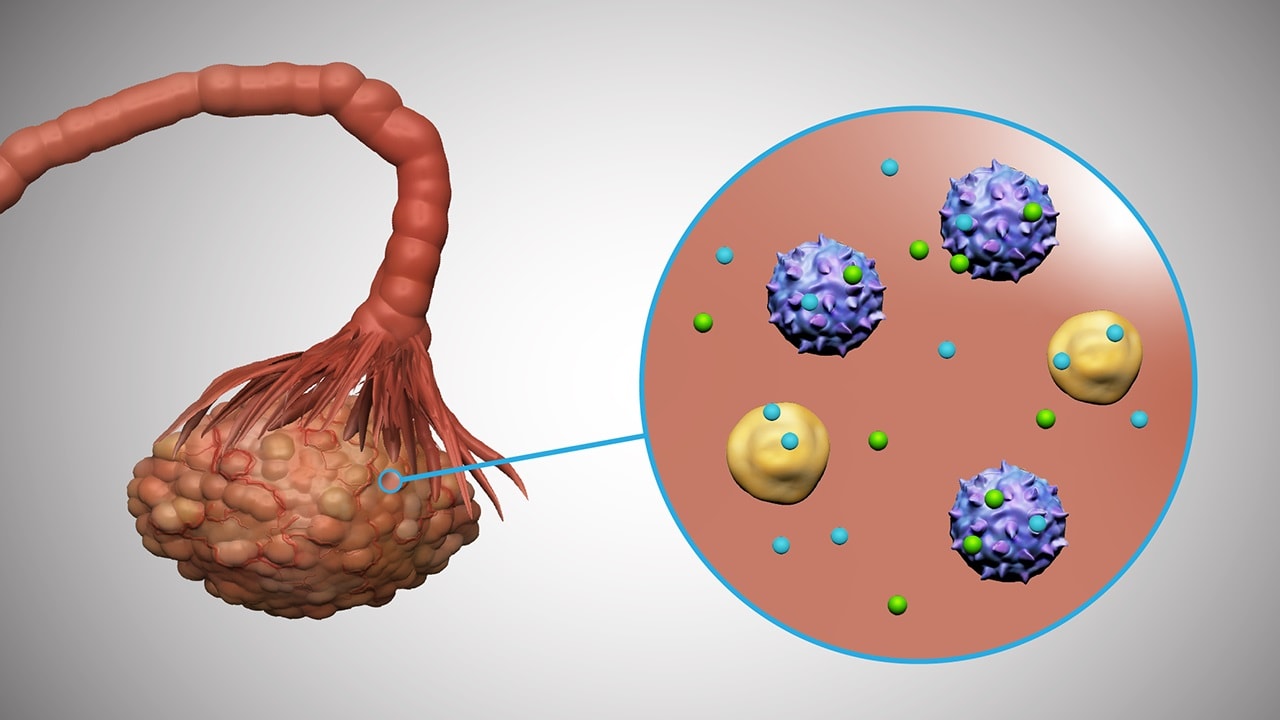

Relevant Anatomy

The term adnexa is derived from the pleural form of the Latin word meaning "appendage." The adnexa of the uterus include the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and structures of the broad ligament. Most frequently, adnexal masses refer to ovarian masses or cysts; however, paratubal cysts, hydrosalpinx, and other nonovarian masses are also included within the broader definition of adnexal masses.

Several other anatomical structures are important to identify, both for the evaluation of other sources of masses within the pelvis and during surgical procedures to prevent damage to nearby organs and structures. The uterus is central to both adnexal regions and can be the source of a pelvic mass. For instance, exophytic, pedunculated fibroids can mimic adnexal masses on preoperative imaging. The rectum and bladder are located posterior and anterior to the adnexal regions. Both can be the source of pelvic masses, although this is less frequent. In addition, they must be protected from injury when adnexal surgery is performed. The ureters are located near the ovarian blood supply and can be damaged easily during adnexal surgery. Many of the pathologic processes associated with adnexal masses can alter the location of the ureters, increasing the chance of damage.

Contraindications

Many adnexal masses can be removed using laparoscopic techniques and are associated with little postoperative complexity. [30] However, in those women with significant preexisting medical problems and/or cancer, major postoperative problems can be encountered and preoperative evaluation is important to assess clearance for surgery (see Postoperative Details and Complications). In patients with significant medical risk factors for surgery, careful consideration of nonsurgical management and follow-up of low-risk adnexal masses is important to avoid unnecessary procedures and risk to the patient.

Prognosis

Most adnexal masses are benign; outcome and prognosis are very good. Generally, no impact on life span or quality of life is noted. In fact, most women treated for adnexal masses have no interruption in their reproductive abilities.

Those women who are found to have malignant adnexal masses fall into 3 groups, as follows:

-

Women ranging in age from the late teens (y) to early 20s (y): Germ cell tumors are seen in these women. The tumors are generally confined to the ovary and are cured in 90% of women after chemotherapy.

-

Women aged 40-60 years: Epithelial tumors are the most common ovarian cancer in these women. These tumors are advanced (stage III-IV) in more than 50% of women. Even after the use of chemotherapy, only 10-40% of patients survive their disease. [31]

-

Women older than 60 years: Ovarian epithelial malignancies are common in this group of patients. Metastatic malignancies are also common. The incidence of sex-cord stromal tumors also increases in incidence in this age group, although it still accounts for only 5% of tumors. Stromal tumors are often early stage and may have an indolent course.

Complications

The major adverse outcomes in the treatment of adnexal masses are related to complications resulting from surgical therapy. These may include the following:

-

Infections of the urinary tract, wound, or lungs

-

Blood loss with the resulting need for transfusion and associated blood-borne infections

-

Injury to surrounding organs such as the urinary bladder, large or small bowel, ureters, or sidewall blood vessels and nerves

-

Pelvic vein thrombosis with associated pulmonary embolism