Practice Essentials

Abdominal angina is defined as the postprandial pain that occurs in individuals who have mesenteric vascular occlusive disease that has advanced to the point where blood flow cannot increase enough to meet visceral demands. [1] This mechanism is similar to that of the angina pectoris that occurs in individuals with coronary artery disease or the intermittent claudication that accompanies peripheral vascular disease.

Schnitzler first described the clinical picture of postprandial pain in 1901. However, the true description of postprandial abdominal angina is attributed to Baccelli or Goodman (1918). In 1957, Mikkelsen proposed surgical treatment of occlusive mesenteric vascular disease. Shaw and Maynard reported the first transarterial thromboendarterectomy of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) in 1958. With the advancements in imaging technology, the degree of stenosis in mesenteric arteries can be defined accurately and treated accordingly.

Patients should be counseled to stop smoking. No effective medical therapy for abdominal angina exists. Mesenteric revascularization relieves the symptoms of abdominal angina. The classic operation for relieving symptoms includes removal of the obstructing lesion, bypass of the obstructed portion of the blood vessel, or both. The less invasive nature of modern endovascular surgery makes it an ideal alternative to bypass surgery for patients with multiple comorbidities. [2] Percutaneous approaches to angioplasty via the brachial or radial artery have been described.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Intestinal ischemia results from an imbalance between oxygen supply to and oxygen consumption by the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Diminished blood flow results from narrowing of the mesenteric vessels. The most frquent cause of abdominal angina is atherosclerotic vascular disease, commonly involving the ostia of the mesenteric vessels.3 Typically, the plaque in the mesenteric vessels is stable; however, a case report described unstable abdominal angina resulting from ruptured atheromatous plaque at the superior mesenteric root. [3]

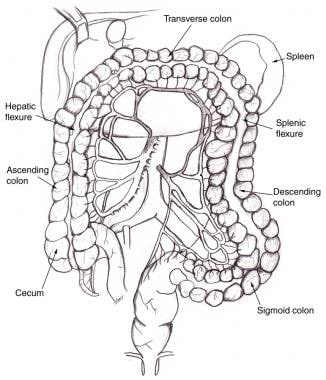

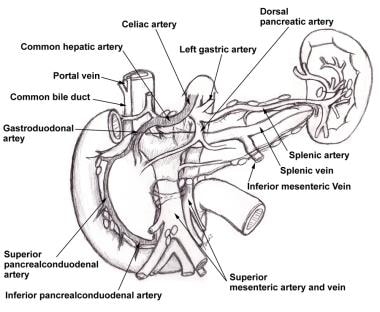

The three arteries supplying the gut are the celiac artery, the SMA, and the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA; see the image below). There are collaterals between the celiac artery and the SMA (pancreaticoduodenal arcades) and between the SMA and the IMA (meandering mesenteric artery). In cases of severe ostial narrowing, internal iliac arteries also serve as important sources of collateral hindgut and midgut perfusion in the presence of IMA occlusion.

Superior mesenteric artery and inferior mesenteric artery share collateral circulation near splenic flexure of colon. When dilated, this vessel is termed meandering mesenteric artery. As seen on angiography, this is sign of chronic mesenteric ischemia.

Superior mesenteric artery and inferior mesenteric artery share collateral circulation near splenic flexure of colon. When dilated, this vessel is termed meandering mesenteric artery. As seen on angiography, this is sign of chronic mesenteric ischemia.

Pancreaticoduodenal arcades are collateral pathways between celiac artery and superior mesenteric artery.

Pancreaticoduodenal arcades are collateral pathways between celiac artery and superior mesenteric artery.

SMA occlusion almost invariably is observed in patients with symptomatic occlusive mesenteric ischemia.

Within a few minutes of eating, there is increased blood flow in the celiac and superior mesenteric vessels in normal individuals. Patients with abdominal angina cannot sufficiently increase flow in the mesenteric vessels. This leads to fear associated with eating and significant weight loss.

The etiology includes the following:

-

Atherosclerosis

-

Smoking

Epidemiology

Abdominal angina is extremely rare, and the true incidence of the syndrome is unknown.

The mean age of affected individuals is slightly older than 60 years. Median arcuate ligament syndrome (Dunbar syndrome [4] ) has been reported in young individuals. In contrast to the usual male predilection of atherosclerotic vascular disease, females outnumber males by approximately 3 to 1 in most series. No data are available regarding relative incidence figures among different races.

Prognosis

Surgical management is the criterion standard for treatment of this disease. [5] Despite advances in surgery, the mortality associated with acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) is in the range of 60-95%.

Reocclusion is more prevalent in males than in females.

Several series have demonstrated that 86-96% of patients remain asymptomatic at 5 and 10 years, with similar graft patency rates.

Research has suggested that after successful endovascular treatment, symptom relief is immediately achieved in 85% of patients. An overall morbidity of 30.8% has been reported. A study by Sarac et al found the most common complication to be access-site hematoma/pseudoaneurysm/thrombosis (15.4%), followed by bowel infarction (4.6%). [6]

A retrospective review by Sundermeyer et al (N = 27) found endovascular SMA treatment to be suitable and safe for patients with chronic mesenteric ischemia (CMI), though the long-term results were limited. [7]

Cai et al carried out a meta-analysis comparing the clinical outcomes of endovascular revascularization for CMI with those of open revascularization. [8] The two approaches were similar with regard to 30-day mortality and 3-year cumulative survival rate. The endovascular approach was associated with a lower rate of in-hospital complications but a higher rate of recurrence within the 3 years following revascularization.

In a retrospective study of 40 patients who underwent acute endovascular revascularization to treat AMI caused by thrombotic occlusion of the celiac artery or the SMA, Pedersoli et al found that although patient mortality remained high overall, nearly 40% of of the subjects survived longer than 1 month. [9] Given the absence of identifiable predictors of outcome, they suggested that all patients with AMI should be offered immediate revascularization.

-

Superior mesenteric artery and inferior mesenteric artery share collateral circulation near splenic flexure of colon. When dilated, this vessel is termed meandering mesenteric artery. As seen on angiography, this is sign of chronic mesenteric ischemia.

-

Pancreaticoduodenal arcades are collateral pathways between celiac artery and superior mesenteric artery.

-

Lateral aortogram shows abrupt cutoffs at origin of visceral vessels and tapered occlusion of distal aorta. Because these vessels originate from anterior surface of the aorta, stenoses and occlusions are not observed clearly on standard anteroposterior views.

-

Arteriogram illustrates meandering mesenteric artery. Appearance of meandering mesenteric artery such as this one supports diagnosis of chronic mesenteric ischemia.

-

Celiac artery is exposed at its origin in preparation for antegrade bypass.

-

Superior mesenteric artery and several branches are exposed for antegrade bypass.

-

Antegrade bypass from aorta to superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and celiac artery (SMA anastomosis is shown) using Dacron graft.

-

Completed retrograde bypass to superior mesenteric artery using expanded polytetrafluoroethylene graft material. Image courtesy of Jamal Hoballah, MD, University of Iowa College of Medicine.

-

Possible incision for trapdoor aortotomy. Plaque at orifices of visceral vessels is removed after trapdoor incision is lifted. When satisfactory endarterectomy has been achieved, trapdoor is sutured shut.

-

Completion duplex ultrasonographic study shows excellent flow at distal anastomosis.

-

Upper gastrointestinal series (barium swallow) shows ulcer.