Practice Essentials

Rectal cancer is a disease in which cancer cells form in the tissues of the rectum; colorectal cancer occurs in the colon or rectum. Adenocarcinomas comprise the vast majority (98%) of colon and rectal cancers; more rare rectal cancers include lymphoma (1.3%), carcinoid (0.4%), and sarcoma (0.3%).

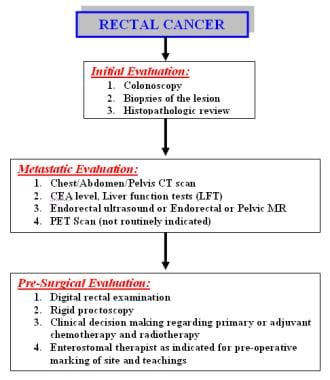

The incidence and epidemiology, etiology, pathogenesis, and screening recommendations are common to both colon cancer and rectal cancer. The image below depicts the staging and workup of rectal cancer.

Signs and symptoms

Bleeding is the most common symptom of rectal cancer, occurring in 60% of patients. However, many rectal cancers produce no symptoms and are discovered during digital or proctoscopic screening examinations.

Other signs and symptoms of rectal cancer may include the following:

-

Change in bowel habits (43%): Often in the form of diarrhea; the caliber of the stool may change; there may be a feeling of incomplete evacuation and tenesmus

-

Occult bleeding (26%): Detected via a fecal occult blood test (FOBT)

-

Abdominal pain (20%): May be colicky and accompanied by bloating

-

Back pain: Usually a late sign caused by a tumor invading or compressing nerve trunks

-

Urinary symptoms: May occur if a tumor invades or compresses the bladder or prostate

-

Malaise (9%)

-

Pelvic pain (5%): Late symptom, usually indicating nerve trunk involvement

-

Emergencies such as peritonitis from perforation (3%) or jaundice, which may occur with liver metastases (< 1%)

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Perform physical examination with specific attention to the size and location of the rectal tumor as well as to possible metastatic lesions, including enlarged lymph nodes or hepatomegaly. In addition, evaluate the remainder of the colon.

Examination includes the use of the following:

-

Digital rectal examination (DRE): The average finger can reach approximately 8 cm above the dentate line; rectal tumors can be assessed for size, ulceration, and presence of any pararectal lymph nodes, as well as fixation to surrounding structures (eg, sphincters, prostate, vagina, coccyx and sacrum); sphincter function can be assessed

-

Rigid proctoscopy: This examination helps to identify the exact location of the tumor in relation to the sphincter mechanism

Laboratory tests

Screening tests may include the following:

-

Guaiac-based FOBT

-

Stool DNA screening (SDNA)

-

Fecal immunochemical test (FIT)

-

Rigid proctoscopy

-

Flexible sigmoidoscopy (FSIG)

-

Combined glucose-based FOBT and flexible sigmoidoscopy

-

Double-contrast barium enema (DCBE)

-

Computed tomography (CT) colonography

-

Fiberoptic flexible colonoscopy (FFC)

Routine laboratory studies in patients with suspected rectal cancer include the following:

-

Complete blood count

-

Serum chemistries

-

Liver and kidney function tests

-

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) test

-

Histologic examination of tissue specimens

Imaging studies

If metastatic (local or systemic) rectal cancer is suspected, the following radiologic studies may be obtained:

-

CT scanning of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis

-

Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): Preferred study

-

Endorectal ultrasonography may be used if pelvic MRI is not readily available

-

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning: Not routinely indicated

See Workup for more detail.

Management

A multidisciplinary approach that includes surgery, medical oncology, and radiation oncology is required for optimal treatment of patients with rectal cancer. Surgical technique, use of radiotherapy, and method of administering chemotherapy are important factors.

Strong considerations should be given to the intent of surgery, possible functional outcome, and preservation of anal continence and genitourinary functions. The first step involves the achievement of a cure, because the risk of pelvic recurrence is high in patients with rectal cancer, and locally recurrent rectal cancer has a poor prognosis.

Surgery

Radical resection of the rectum is the mainstay of therapy. The timing of surgical resection is dependent on the size, location, extent, and grade of the rectal carcinoma. Operative management of rectal cancer may include the following:

-

Transanal excision: For early-stage cancers in a select group of patients

-

Transanal endoscopic microsurgery: A form of local excision that uses a special operating proctoscope that distends the rectum with insufflated carbon dioxide and allows the passage of dissecting instruments

-

Endocavity radiotherapy: Delivered under sedation via a special proctoscope in the operating room

-

Sphincter-sparing procedures: Low anterior resection, coloanal anastomosis, abdominal perineal resection

Adjuvant medical management

Adjuvant medical therapy may include the following:

-

Adjuvant radiation therapy

-

Intraoperative radiation therapy

-

Adjuvant chemotherapy

-

Adjuvant chemoradiation therapy

-

Radioembolization

Pharmacotherapy

National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend the use of as many chemotherapy drugs as possible to maximize the effect of adjuvant therapies for colon and rectal cancer. [1]

The following agents may be used in the management of rectal cancer:

-

Antineoplastic agents (eg, fluorouracil, vincristine, leucovorin, irinotecan, oxaliplatin, cetuximab, bevacizumab, panitumumab)

-

Vaccines (eg, quadrivalent human papillomavirus [HPV] vaccine)

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Colon and rectal cancer incidence was negligible before 1900. The incidence of colorectal cancer rose dramatically following economic development and industrialization. Currently, colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer deaths in both males and females in the United States. [2]

Adenocarcinomas comprise the vast majority (98%) of colon and rectal cancers. Other rare rectal cancers, including carcinoid (0.4%), lymphoma (1.3%), and sarcoma (0.3%), are not discussed in this article. Squamous cell carcinomas may develop in the transition area from the rectum to the anal verge and are considered anal carcinomas. Very rare cases of squamous cell carcinoma of the rectum have been reported. [3, 4]

Approximately 20% of colorectal cancers develop in the cecum, another 20% in the rectum, and an additional 10% in the rectosigmoid junction. Approximately 25% of colon cancers develop in the sigmoid colon. [3]

The incidence and epidemiology, etiology, pathogenesis, and screening recommendations are common to both colon cancer and rectal cancer. These areas are addressed together.

Anatomy

The surgical definition of the rectum differs from the anatomical definition; surgeons define the rectum as starting at the level of the sacral promontory, while anatomists define the rectum as starting at the level of the 3rd sacral vertebra. Therefore, the measured length of the rectum varies from 12 cm to 15 cm. The rectum differs from the rest of the colon in that the outer layer consists of longitudinal muscle. The rectum contains three folds, namely the valves of Houston. The superior (at 10 cm to 12 cm) and inferior (at 4 cm to 7 cm) folds are located on the left side and the middle fold (at 8 cm to 10 cm) is located at the right side.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines define rectal cancer as cancer located within 12 cm of the anal verge by rigid proctoscopy. [1] This definition was developed by the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group study, which found that the risk of recurrence of rectal cancer depends on the location of the cancer. Univariate sub-group analyses showed that the treatment effect for surgery alone vs preoperative radiotherapy plus surgery was not significant in patients whose cancer (TNM stage I to IV) was located between 10.1 cm and 15 cm from the anal verge. [5]

Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging is the most common modality to define the anatomic rectum. The variations in the definition of anatomic rectum result in variations in the treatment options, most importantly determining whether neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy is indicated. Neoadjuvant therapy has significant consequences in the functional and oncologic outcomes of patients.

The following features are used to define the rectum apart from the sigmoid colon [6] :

-

The sacral promontory

-

The third valve of Houston

-

The coalescence of tenia of sigmoid

-

The transition from sigmoid mesocolon to mesorectum

-

Loss of appendiceal epiploicae

-

Anterior peritoneal reflection

In order to standardize treatment of colorectal cancer, an international group of colorectal experts established a consensus definition of the anatomic rectum, using the Delphi technique. This consensus meeting came up with new terminology, the sigmoid takeoff, which defines the junction of sigmoid colon and rectum and the junction of sigmoid mesocolon and mesorectum radiographically. [6] Although there are many publications on this topic in the literature, all rectal surgeons should familiarize themselves with the Delphi consensus article, as well as "The 'Holy Plane' of rectal surgery", which defines an optimal dissection plane around rectal tumors in terms of the pelvic fascia. [6, 7]

Pathophysiology

The mucosa in the large intestine regenerates approximately every 6 days. Crypt cells migrate from the base of the crypt to the surface, where they undergo differentiation and maturation, and ultimately lose the ability to replicate.

The significant portions of colorectal carcinomas are adenocarcinomas. The adenoma-carcinoma sequence is well described in the medical literature. [3] Colonic adenomas precede adenocarcinomas. Approximately 10% of adenomas will eventually develop into adenocarcinomas. This process may take up to 10 years. [3]

Three pathways to colon and rectal carcinoma have been described:

-

Adenomatous polyposis coli ( APC) gene adenoma-carcinoma pathway

-

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) pathway

-

Ulcerative colitis dysplasia

The APC adenoma carcinoma pathway involves several genetic mutations, starting with inactivation of the APC gene, which allows unchecked cellular replication at the crypt surface. With the increase in cell division, further mutations occur, resulting in activation of the K-ras oncogene in the early stages and p53 mutations in later stages. These cumulative losses in tumor suppressor gene function prevent apoptosis and prolong the cell's lifespan indefinitely. If the APC mutation is inherited, it will result in familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome.

Histologically, adenomas are classified in three groups: tubular, tubulovillous, and villous adenomas. K-ras mutations and microsatellite instability have been identified in hyperplastic polyps. Therefore, hyperplastic polyps may also have malignant potential in varying degrees. [8]

The other common carcinogenic pathway involves mutation in DNA mismatch repair genes. Many of these mismatched repair genes have been identified, including hMLH1, hMSH2, hPMS1, hPMS2, and hMSH6. Mutation in mismatched repair genes negatively affects the DNA repair. This replication error is found in approximately 90% of HNPCC and 15% of sporadic colon and rectal cancers. [3, 9] A separate carcinogenic pathway is also described in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Chronic inflammation such as in ulcerative colitis can result in genetic alterations which then lead into dysplasia and carcinoma formation. [3]

Epidemiology

United States

Colon and rectal cancer is the third most common cancer in both females and males. The American Cancer Society (ACS) estimates that 106,970 new cases of colon cancer and 46,050 new cases of rectal cancer will occur in 2023; 27,440 cases of rectal cancer are expected in men and 18,610 in women. For estimates of deaths, the ACS combines colon and rectal cancers, because many deaths from rectal cancer are misclassified as due to colon cancer on death certificates; approximately 52,550 deaths from colorectal cancer are expected to occur in 2023. [2]

The incidence of colorectal cancer has generally declined since the mid-1980s. The decrease has accelerated since 2000, thanks largely to greater use of screening. However, the overall trend is driven by older adults (who have the highest rates) and masks the situation in younger adults, who have experienced rising incidence rates since at least the mid-1990s. From 2011 to 2019, incidence rates decreased by about 1% per year in adults 50 and older, but rates in persons younger than 50 years have increased by 1%-2% per year since the mid-1990s. [2] Currently, adults born circa 1990 have quadruple the risk of rectal cancer compared with those born circa 1950. [10]

The overall death rate from colorectal cancer has also been falling, decreasing 56% from 1970 to 2019—from 29.2 to 12.8 per 100,000, respectively—because of changing patterns in risk factors, increased screening, and improvements in treatment. From 2015 to 2019, the death rate declined by almost 2% per year. As with incidence rates, however, the decrease in overall mortality masks the rise in death rates in adults younger than 55 years. [2]

Tumor site tends to vary by patient age. In those aged younger than 65 years, the rectum is the most common site of colorectal cancer, accounting for 37% of cases in those under age 50 years and 36% in those 50 to 64 years of age. In individuals age 65 and older, rectal cancer accounts for 23% of colorectal cancer cases; the proximal colon is the most common site, accounting for 49% of cases. [11]

International

Although the incidence of colon and rectal cancer varies considerably by country, an estimated 1,931,590 cases occurred worldwide in 2020. High incidences of colon and rectal cancer cases are identified in the US, Canada, Japan, parts of Europe, New Zealand, Israel, and Australia. Low colorectal cancer rates are identified in Algeria and India. The majority of colorectal cancers still occur in industrialized countries. [12]

Increases in colorectal cancer in persons younger than 50 years has also been in many other high‐income countries aside from the US, including Australia, Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom. In Austria, however, where opportunistic screening has been used in individuals aged 40 years and older since the 1980s, rates of colorectal cancer are increasing in those aged 20 to 39 years but decreasing in those age 40 to 49 years. [11]

Race

The incidence of colorectal cancer tends to be higher in Western nations than in Asian and African countries; however, within the United States, differences in incidence exist among Whites, Blacks, and Asians: the rate of new cases per 100,000 population is highest in Blacks (52.4 in men, 38.6 in women), then Whites (43.5 in men, 33.3 in women), then Hispanics (41.1 in men, 29.0 in women). In the US, Black men have the highest mortality (22.3 per 100,000 population) and Asian/Pacific Islander women and Hispanic women have the lowest mortality (7.7 and 8.5 per 100,000 population, respectively). [13] However, the incidence of colorectal cancer among people younger than 50 years is increasing much faster in Whites than in Blacks (2% vs 0.5% per year, respectively). [11]

A study by Yothers et al found that Black patients with resected stage II and stage III colon cancer had worse overall and recurrence-free survival compared with White patients who underwent the same therapy. [14]

A study of racial disparities in mortality rates between Black and White individuals with colorectal cancer by Robbins et al showed earlier and larger reductions in death rates for Whites from 1985-2008. [15] This racial disparity could be decreased with greater education to the Black population regarding colorectal cancer prevention and access to treatment, including colonoscopies and polypectomies.

Sex

The incidence of colorectal malignancy is slightly higher in males than in females. The overall age-adjusted incidence of colorectal cancer in all races was 43.4 per 100,000 for males and 32.8 per 100,000 for females in 2015-2019, yielding a male-female ratio of 1.32:1. Mortality rates for colorectal cancer in 2016-2020 were also higher in males (15.7 per 100,000) than in females (11.0 per 100,000). [13]

Age

The incidence of colorectal cancer starts to increase after age 35 and rises rapidly after age 50, peaking in the seventh decade. More than 90% of colon cancers occur after age 50. However, cases have been reported in young children and adolescents. [3] The incidence rates of colorectal cancer increased by about 2% per year in adults younger than age 55 from 2006 to 2015, largely because of increases in rectal cancer. [2]

Mortality/Morbidity

The American Cancer Society estimates that in 2023, colorectal cancer will account for 9% of cancer deaths in men and 8% in women. In the US, mortality rates have been decreasing in both sexes for the past 2 decades. The 5-year relative survival rate is 65.1% for colorectal cancer; however, for patients who are diagnosed with localized disease, the 5-year survival rate is 90.9%. [13]

A review of eight trials by Rothwell et al found that allocation to aspirin reduced death caused by cancer. Individual patient data were available from seven of the eight trials. Benefit was apparent after 5 years of follow-up. The 20-year risk of cancer death was also lower in the aspirin group for all solid cancers. A latent period of 5 years was observed before risk of death was decreased for esophageal, pancreatic, brain, and lung cancers. A more delayed latent period was observed for stomach, colorectal, and prostate cancer. Benefit was only seen for adenocarcinomas in lung and esophageal cancers. The overall effect on 20-year risk of cancer death was greatest for adenocarcinomas. [16]

A study by Banks et al showed the benefit of aspirin in preventing colon adenocarcinoma among patients with hereditary risk of colorectal cancer. In a study of 861 patients, 600 mg of aspirin daily for a mean of 25 months substantially reduced cancer incidence after 55.7 months among carriers of hereditary colorectal cancer. Further studies are needed to determine the ideal dosage and duration. [17]

In a review of 51 randomized controlled trials, Rothwell et al found that aspirin reduced the short-term incidence of cancer and the short- and long-term risk of cancer death. The authors conclude that their results support the use of daily aspirin for cancer prevention. [18]

Prognosis

The 5-year relative survival rates for colorectal cancer based on SEER stage are as follows [13] :

-

Localized - 90.9%

-

Regional - 72.8%

-

Distant - 15.1%

-

Unknown - 40.5%

-

All stages - 65.1%

A review of 111,453 patients in the National Cancer Data Base who were diagnosed with early-stage (T1N0 or T2N0) rectal cancer from 1998 to 2010 found that increasing age, male sex, higher comorbidity score, and positive or unknown final surgical margins were associated with poorer long-term adjusted overall survival. [19]

Recurrence of rectal cancer, which usually develops in the first year after surgery, carries a poor prognosis. Recurrence may be local, distant, or both; local recurrence is more common in rectal cancer than in colon cancer. Reported rates of local recurrence have ranged from 3.7% to 50%. [20] Factors that influence the development of recurrence include the following:

-

Surgeon variability

-

Grade and stage of the primary tumor

-

Location of the primary tumor (eg, low rectal cancers have higher rates of recurrence

-

Ability to obtain negative margins

Surgical therapy may be attempted for recurrence and includes pelvic exenteration or abdominal perineal resection in patients who had a sphincter-sparing procedure. Radiation therapy generally is used as palliative treatment in patients who have locally unresectable disease.

Patient Education

A study by Thong et al found that survivors of rectal cancer may benefit from increased focus, both clinical and psychological, on the possible long-term morbidity of treatment and its effects on health. [21]

For patient education resources, see Rectal Cancer.

-

Diagnostics. Staging and workup of rectal cancer patients.

-

Staging and treatment. Rectal cancer treatment algorithm (surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy). Initial stages are Endorectal ultrasound staging (uT).