Practice Essentials

An ovarian cyst is a sac filled with liquid or semiliquid material that arises in an ovary (see the image below). Although the discovery of an ovarian cyst causes considerable anxiety in women owing to fears of malignancy, the vast majority of these lesions are benign.

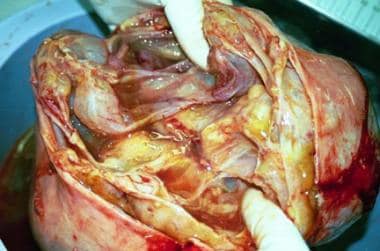

A multilocular right ovarian cyst that is 24 cm in diameter. It is seen with the adjacent fallopian tube and uterus. The infundibulo-pelvic ligament carrying the ovarian artery and vein has been divided. Histology reported a mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of low malignant potential. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

A multilocular right ovarian cyst that is 24 cm in diameter. It is seen with the adjacent fallopian tube and uterus. The infundibulo-pelvic ligament carrying the ovarian artery and vein has been divided. Histology reported a mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of low malignant potential. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

Signs and symptoms

Most patients with ovarian cysts are asymptomatic, with the cysts being discovered incidentally during ultrasonography or routine pelvic examination. Some cysts, however, may be associated with a range of symptoms, sometimes severe, including the following [1] :

-

Pain or discomfort in the lower abdomen

-

Discomfort with intercourse, particularly deep penetration

-

Changes in bowel movements such as constipation

-

Pelvic pressure causing tenesmus or urinary frequency

-

Menstrual irregularities [3]

-

Precocious puberty and early menarche in young children

-

Abdominal fullness and bloating

-

Indigestion, heartburn, or early satiety

-

Endometriomas - These are associated with endometriosis, which causes a classic triad of painful and heavy periods and dyspareunia

-

Tachycardia and hypotension - These may result from hemorrhage caused by cyst rupture

-

Hyperpyrexia - This may result from some complications of ovarian cysts, such as ovarian torsion [1]

-

Adnexal or cervical motion tenderness

-

Underlying malignancy may be associated with early satiety, weight loss/cachexia, lymphadenopathy, or shortness of breath related to ascites or pleural effusion

Palpation

A large cyst may be palpable on abdominal examination, but gross ascites may interfere with palpation of an intra-abdominal mass. The cyst may be tender to palpation.

Other masses may be palpable, including fibroids and nodules in the uterosacral ligament consistent with malignancy or endometriosis

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Per ACOG and other guidelines, transvaginal ultrasound is the preferred imaging modality for assessment of a suspected pelvic mass. [4, 5]

The definitive diagnosis of all ovarian cysts is made based on histologic analysis. Each cyst type has characteristic findings.

Laboratory tests, although not diagnostic for ovarian cysts, may aid in the differential diagnosis of cysts and in the diagnosis of cyst-related complications. Studies include the following:

-

Urinary pregnancy test

-

Complete blood count (CBC)

-

Urinalysis

-

Endocervical swabs if infectious etiology is suspected

-

Serum biomarker testing

Cancer antigen 125 (CA125) - The finding of an elevated CA125 level is most useful when combined with an ultrasonographic investigation while assessing a postmenopausal woman with an ovarian cyst [1, 6]

hCG, L-lactated dehydrogenase, alpha-fetoprotein, and inhibin may be helpful if a less common histology is suspected [4]

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Many patients with simple ovarian cysts found through ultrasonographic examination do not require treatment. In a postmenopausal patient, a persistent simple cyst smaller than 10 cm in dimension in the presence of a normal CA125 value may be monitored with serial ultrasonographic examinations. [3, 7, 4]

Pharmacologic therapy

Oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) protect against the development of functional ovarian cysts. Existing functional cysts, however, do not regress more quickly when treated with combined oral contraceptives than they do with expectant management. [8]

Laparotomy and laparoscopy

Persistent simple ovarian cysts larger than 10 cm (especially if symptomatic) and complex ovarian cysts should be considered for surgical removal. The surgical approaches include an open technique (laparotomy) or a minimally invasive technique (laparoscopy) with very small incisions. The latter approach is preferred in cases presumed benign. [4] Removing the cyst intact for pathologic analysis may mean removing the entire ovary, though a fertility sparing surgery should be attempted in younger women. [4]

Bilateral oophorectomy

Bilateral oophorectomy and, often, hysterectomy are performed in many postmenopausal women with ovarian cysts, because of the increased incidence of neoplasms in this population.

Referral

Per ACOG Guidelines, referral to a gynecologic oncologist is recommended for the following patients: [4]

-

Postmenopausal patient with elevated CA125, imaging findings consistent with malignancy, ascites, a nodular or fixed mass, or evidence of metastases

-

Premenopausal patient with very elevated CA125, imaging findings consistent with malignancy, ascites, a nodular or fixed mass, or evidence of metastases

-

Premenopausal or postmenopausal patient with elevated malignancy predictive score such as the multivariate index assay, risk of malignancy index, or the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm, or one of the ultrasound-based scoring systems from the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis Group

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

An ovarian cyst is a sac filled with liquid or semiliquid material that arises in an ovary. The number of diagnoses of ovarian cysts has increased with the widespread implementation of regular physical examinations and ultrasonographic technology. The discovery of an ovarian cyst causes considerable anxiety in women owing to fears of malignancy, but the vast majority of ovarian cysts are benign. (See Prognosis, Presentation, and Workup.)

These cysts can develop in females at any stage of life, from the neonatal period to postmenopause. Most ovarian cysts, however, occur during infancy and adolescence, which are hormonally active periods of development. Most are functional in nature and resolve without treatment. (See Epidemiology, Prognosis, Treatment, and Medication.)

However, ovarian cysts can herald an underlying malignant process or, possibly, distract the clinician from a more dangerous condition, such as ectopic pregnancy, ovarian torsion, or appendicitis. (On the other hand, there may be an inverse relationship between ovarian cysts and breast cancer. [9, 10] ) (See Presentation and Workup.)

When ovarian cysts are large, persistent, painful, or have concerning radiographic or exam findings, surgery may be required, sometimes resulting in removal of the ovary. A large ovarian cyst is shown in the images below. (See Treatment.)

A multilocular right ovarian cyst that is 24 cm in diameter. It is seen with the adjacent fallopian tube and uterus. The infundibulo-pelvic ligament carrying the ovarian artery and vein has been divided. Histology reported a mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of low malignant potential. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

A multilocular right ovarian cyst that is 24 cm in diameter. It is seen with the adjacent fallopian tube and uterus. The infundibulo-pelvic ligament carrying the ovarian artery and vein has been divided. Histology reported a mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of low malignant potential. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

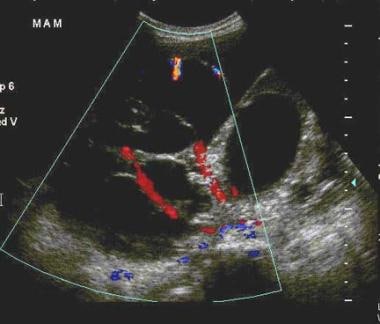

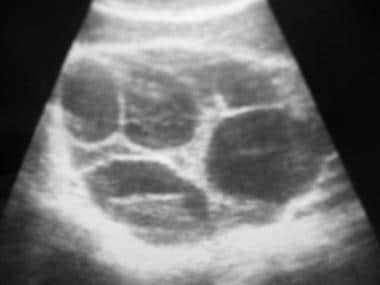

Transabdominal sonogram of a multilocular right ovarian cyst that is 24 cm in diameter, with the adjacent fallopian tube and uterus. The infundibulo-pelvic ligament carrying the ovarian artery and vein has been divided. This sonogram demonstrates a large, complex cystic mass with vascularity within the septations. Red and blue colors show blood flow towards and away from the transducer. The resistive index was low. Histology reported a mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of low malignant potential. Courtesy Patrick O'Kane, MD.

Transabdominal sonogram of a multilocular right ovarian cyst that is 24 cm in diameter, with the adjacent fallopian tube and uterus. The infundibulo-pelvic ligament carrying the ovarian artery and vein has been divided. This sonogram demonstrates a large, complex cystic mass with vascularity within the septations. Red and blue colors show blood flow towards and away from the transducer. The resistive index was low. Histology reported a mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of low malignant potential. Courtesy Patrick O'Kane, MD.

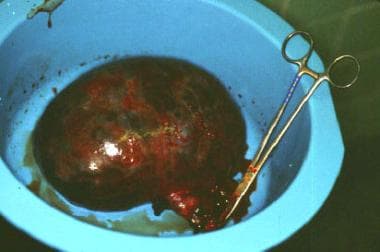

A multilocular right ovarian cyst that is 24 cm in diameter has been removed and cut open. It has a smooth surface and a multicystic internal structure. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

A multilocular right ovarian cyst that is 24 cm in diameter has been removed and cut open. It has a smooth surface and a multicystic internal structure. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

Emergency diagnosis

Abdominal pain in the female can be one of the most difficult cases to diagnose correctly in the emergency department (ED). The spectrum of gynecologic disease is broad, spanning all age ranges and representing various degrees of severity, from benign cysts that eventually resolve on their own to ruptured ectopic pregnancy that causes life-threatening hemorrhage. (See Prognosis.)

When presented with this scenario, the goal of the emergency physician is to rule out acute causes of abdominal pain associated with high morbidity and mortality, such as appendicitis, ovarian torsion, or ectopic pregnancy; to assess for the possibility of neoplasm or malignancy; and either to refer the patient to the appropriate consultant or to discharge them with a clear plan for follow-up with an obstetrician/gynecologist. (See Presentation, DDx, and Workup.)

Patient education

Provide patients with adequate discharge and follow-up instructions and information, including documentation of the potential risks of infertility, disability, and malignancy caused by delays or noncompliance.

For patient education information, see the Women's Health Center and the Cancer Center, as well as Ovarian Cysts, Female Sexual Problems, and Ovarian Cancer.

Pathophysiology

Functional cysts

The median menstrual cycle lasts 28 days, beginning with the first day of menstrual bleeding and ending just before the subsequent menstrual period. The variable first half of this cycle is termed the follicular phase and is characterized by increasing follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) production, leading to the selection of a dominant follicle that is primed for release from the ovary. [11]

In a normally functioning ovary, simultaneous estrogen production from the dominant follicle leads to a surge of luteinizing hormone (LH), resulting in ovulation and the release of the dominant follicle from the ovary and commencing the luteinizing phase of ovulation.

After ovulation, the follicular remnants form a corpus luteum, which produces progesterone. This, in turn, supports the released ovum and inhibits FSH and LH production. As luteal degeneration occurs in the absence of pregnancy, the progesterone levels decline, while the FSH and LH levels begin to rise before the onset of the next menstrual period.

Follicular cysts

Different kinds of functional ovarian cysts can form during this cycle. In the follicular phase, follicular cysts may result from a lack of physiologic release of the ovum due to excessive FSH stimulation or lack of the normal LH surge at midcycle just before ovulation. Hormonal stimulation causes these cysts to continue to grow. Follicular cysts are typically larger than 2.5 cm in diameter and manifest as a discomfort and heaviness. Granulosa cells that line the follicle may also persist, leading to excess estradiol production, which, in turn, leads to decreased frequency of menstruation and menorrhagia. [12]

Corpus luteal cysts

In the absence of pregnancy, the lifespan of the corpus luteum is 14 days. If the ovum is fertilized, the corpus luteum continues to secrete progesterone for 5-9 weeks, until its eventual dissolution in 14 weeks’ time, when the cyst undergoes central hemorrhage. Failure of dissolution to occur may result in a corpus luteal cyst, which is arbitrarily defined as a corpus luteum that grows to 3 cm in diameter. The cyst can cause dull, unilateral pelvic pain and may be complicated by rupture, which causes acute pain and possibly massive blood loss.

Theca-lutein cysts

Theca-lutein cysts are caused by luteinization and hypertrophy of the theca interna cell layer in response to excessive stimulation from human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) These cysts are predisposed to torsion, hemorrhage, and rupture.

Theca-lutein cysts can occur in the setting of gestational trophoblastic disease (hydatidiform mole and choriocarcinoma), multiple gestation, or exogenous ovarian hyperstimulation.

These cysts are associated with maternal androgen excess in up to 30% of cases but usually resolve spontaneously as the hCG level falls. Theca-lutein cysts are usually bilateral and result in massive ovarian enlargement, a characteristic of the condition termed hyperreactio luteinalis. [13] (See the image below.)

Theca-lutein cysts replacing an ovary in a patient with a molar pregnancy. Despite their size these cysts are benign and usually resolve after treatment of the underlying disease. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

Theca-lutein cysts replacing an ovary in a patient with a molar pregnancy. Despite their size these cysts are benign and usually resolve after treatment of the underlying disease. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

Luteoma of pregnancy

A luteoma of pregnancy results when ovarian parenchyma is replaced by proliferation of luteinized stromal cells that may become hormonally active with production of androgens. Maternal virilization can occur in up to 30% of cases, with a 50% risk of virilization of the female fetus; male fetuses are unaffected. Luteoma of pregnancy appears as complex, heterogenous, hypoechoic mass on ultrasonography. After completion of pregnancy, the mass typically resolves and testosterone levels typically normalize. [14]

Neoplastic cysts

Neoplastic cysts arise via the inappropriate overgrowth of cells within the ovary and may be malignant or benign. Malignant neoplasms may arise from all ovarian cell types and tissues. The most frequent by far, however, are those arising from the surface epithelium (mesothelium); most of these are partially cystic lesions. The benign counterparts of these cancers are serous and mucinous cystadenomas. Other malignant ovarian tumors may also contain cystic areas, including granulosa cell tumors from sex cord stromal cells and germ cell tumors from primordial germ cells. Cystic spaces within a tumor are seen in the image below.

Cross-section of a clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Note the cystic spaces intermingled with solid areas. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

Cross-section of a clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Note the cystic spaces intermingled with solid areas. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

Teratomas

Teratomas are a form of germ cell tumor [15] containing elements from all 3 embryonic germ layers, ie, ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm. A mature cystic teratoma is shown in the image below.

A dermoid cyst (mature cystic teratoma) after opening the abdomen. Note the yellowish color of the contents seen through the wall. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

A dermoid cyst (mature cystic teratoma) after opening the abdomen. Note the yellowish color of the contents seen through the wall. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

Endometriomas

Endometriomas are blood-filled cysts arising from the ectopic endometrium. Endometriomas are associated with endometriosis, which can cause dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia.

Polycystic ovarian syndrome

In polycystic ovarian syndrome, the ovary often contains multiple cystic follicles 2-5 mm in diameter as viewed on sonograms. The cysts themselves are never the main problem, and discussion of this disease is beyond the scope of this article.

Risk factors

Risk factors for ovarian cyst formation include the following:

-

Infertility treatment - Patients being treated for infertility by ovulation induction with gonadotropins or other agents, such as clomiphene citrate or letrozole, may develop cysts as part of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome

-

Tamoxifen - Tamoxifen can cause benign functional ovarian cysts that usually resolve following discontinuation of treatment

-

Pregnancy - In pregnant women, ovarian cysts may form in the second trimester, when hCG levels peak [13]

-

Hypothyroidism - Because of similarities between the alpha subunit of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and hCG, hypothyroidism may stimulate ovarian and cyst growth [6]

-

Maternal gonadotropins - The transplacental effects of maternal gonadotropins may lead to the development of neonatal and fetal ovarian cysts [16]

-

Tubal ligation - Functional cysts have been associated with tubal ligation sterilizations [19]

Risk factors for ovarian cystadenocarcinoma include the following:

-

Strong family history

-

Advancing age

-

White race

-

Infertility

-

Nulliparity

-

History of breast cancer

-

BRCA gene mutations

Epidemiology

Occurrence in the United States

Ovarian cysts are found on transvaginal sonograms in nearly all premenopausal women and in up to 18% of postmenopausal women (women develop one or more Graafian follicles each menstrual cycle, which appear as cysts on imaging). [1, 6, 20] Most of these cysts are functional in nature and benign. Mature cystic teratomas, or dermoids, represent more than 10% of all ovarian neoplasms. Ovarian cysts are the most common fetal and infant tumor, with a prevalence exceeding 30%. [21]

The incidence of ovarian carcinoma is approximately 15 cases per 100,000 women per year. In the United States, ovarian carcinomas are diagnosed in more than 21,000 women annually, causing an estimated 14,600 deaths. [22] Most malignant ovarian tumors are epithelial ovarian cystadenocarcinomas.

Tumors of low malignant potential make up approximately 20% of malignant ovarian tumors, whereas less than 5% are malignant germ cell tumors, and approximately 2% are granulosa cell tumors. [23]

Race-related demographics

Malignant epithelial ovarian cystadenocarcinomas are the only ovarian cysts associated with a race predilection. Women from northern and western Europe and North America are affected most frequently, whereas women from Asia, Africa, and Latin America are affected least frequently.

Within the United States, age-adjusted incidence rates in surveillance areas are highest among American Indian women, followed by white, Vietnamese, Hispanic, and Hawaiian women. Incidence is lowest among Korean and Chinese women. [24]

Among women for whom sufficient numbers of cases are available to calculate rates based on age, incidence in those aged 30-54 years is highest in white women, followed by Japanese, Hispanic, and Filipino women. For women aged 55-69 years, the highest rates occur in white women, followed by Hispanic and Japanese women. Among women aged 70 years or older, the highest rate occurs among white women, followed by those of African descent and Hispanic women.

Age-related demographics

Functional ovarian cysts can occur at any age (including in utero) but are much more common in women of reproductive age. They are rare after menopause. Luteal cysts occur after ovulation in reproductive-age women. Most benign neoplastic cysts occur during the reproductive years, but the age range is wide and they may occur in persons of any age.

The incidence of epithelial ovarian cystadenocarcinomas, sex cord stromal tumors, and mesenchymal tumors rises exponentially with age until the sixth decade of life, at which point the incidence plateaus.

Tumors of low malignant potential occur at a mean age of 44 years, with a span from adolescence to senescence. The average age is more than a decade less than that for invasive cystadenocarcinoma. Germ cell tumors are most common in adolescence and rarely occur in women older than 30 years.

In a child found to have a symptomatic abdominopelvic mass, the ovary is the most common site of origin. Although such masses are infrequent occurrences, the percentage due to malignant tumors is thought to be higher than for older age groups. The most common are germ cell tumors, followed by epithelial and granulosa cell tumors. Such tumors may be partially cystic.

Prognosis

The prognosis for benign cysts is excellent. All such cysts may occur in residual ovarian tissue or in the contralateral ovary. Overall, 70%-80% of follicular cysts resolve spontaneously.

A 2-year interim analysis from the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis Phase 5 (IOTA5) study showed that 80% of ovarian cysts considered benign on ultrasonography either disappeared or required no intervention. Only 12 of the 1919 women in the study received a diagnosis of ovarian cancer; thus, the 2-year cumulative risk of cancer was 0.4%. [25]

Malignancy is a common concern among patients with ovarian cysts. Pregnant patients with simple cysts smaller than 6cm in diameter have a malignancy risk of less than 1%. Most of these cysts resolve by 16-20 weeks' gestation, with 96% of these masses resolving spontaneously. [26] In postmenopausal patients with unilocular cysts, malignancy develops in 0.3% of cases. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Liu et al found that the malignancy rate (including borderline tumors) for simple ovarian cysts in postmenopausal women was approximately 1 in 10,000. [27]

In complex, multiloculated cysts, the risk of malignancy climbs to 36%. If cancer is diagnosed, regional or distant spread may be present in up to 70% of cases, and only 25% of new cases will be limited to stage I disease. [20]

Mortality associated with malignant ovarian carcinoma is related to the stage at the time of diagnosis, and patients with this carcinoma tend to present late in the course of the disease. The 5-year survival rate overall is 41.6%, varying between 86.9% for International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage Ia and 11.1% for stage IV.

A distinct group of less aggressive tumors of low malignant potential runs a more benign course but still is associated with definite mortality. The overall survival rate is 86.2% at 5 years. [14]

The potential of benign ovarian cystadenomas to become malignant has been postulated but, to date, remains unproven. Malignant change can occur in a small percentage of dermoid cysts (associated with an extremely poor prognosis) and endometriomas.

Complications

Ovarian cysts have a broad range of potential outcomes. In most cases, the cyst is benign and asymptomatic, requires no further management, and will resolve on its own. In other cases, ovarian cyst–related accidents, such as rupture and hemorrhage or torsion, occur.

Torsion

Ovarian cysts larger than 4 cm in diameter have been shown to have a torsion rate of approximately 15%. Ovarian torsion involves the rotation of the ovarian vascular pedicle, causing obstruction to venous and, eventually, arterial flow that can lead to infarction. (See the image below.)

An ovarian cyst that underwent torsion (twisting of the vascular pedicle). The patient presented with a short history of severe lower abdominal pain. The twisted pedicle can be seen attached to the cyst, which has turned dusky due to ischemia. No viable epithelial lining was available for histologic diagnosis. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

An ovarian cyst that underwent torsion (twisting of the vascular pedicle). The patient presented with a short history of severe lower abdominal pain. The twisted pedicle can be seen attached to the cyst, which has turned dusky due to ischemia. No viable epithelial lining was available for histologic diagnosis. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

Most torsion cases occur in premenopausal females of childbearing age, but up to 17% of cases affect prepubertal and postmenopausal women. It is also strongly associated with ovarian stimulation and polycystic ovarian syndrome. Ovarian torsion is more common on the right side owing to the sigmoid colon restricting the mobility of the left ovary.

Malignancy may be seen in up to 2% of cases of ovarian torsion. The most common ovarian mass associated with torsion is a dermoid cyst.

CT scanning and ultrasonography can assist with diagnosis. The absence of blood flow within an ovary can support the diagnosis of torsion but is neither sensitive nor specific. Treatment options include laparoscopic “detorsion” and adnexal preservation in premenopausal women and salpingo-oophorectomy in postmenopausal women. Ovarian function may be preserved with laparoscopic detorsion in 90% of cases.

Rupture

The outcome of ovarian cyst rupture is evaluated based on associated symptoms and will dictate whether the patient is discharged or admitted for laparoscopy.

Ovarian cyst rupture commonly occurs with corpus luteal cysts. They involve the right ovary in two thirds of cases and usually occur on days 20-26 of the woman’s menstrual cycle. Mittelschmerz is a form of physiologic cyst rupture. In pregnant women, hemorrhagic corpus luteal cysts are usually seen in the first trimester, with most resolving by 12 weeks' gestation. Hemorrhage and shock may occur and may present late in the symptomatology.

In ovarian cyst rupture, ultrasonography may demonstrate free fluid in the pouch of Douglas in 40% of cases. Cyst rupture and hemorrhage may be treated conservatively with observation if the patient is stable, with follow-up scanning in 6 weeks to confirm hemorrhage resolution. Laparoscopy is indicated in hemodynamic compromise, possibility of torsion, no relief of symptoms within 48 hours, or increasing hemoperitoneum or falling hemoglobin concentration. The hemoperitoneum that results from a ruptured hemorrhagic ovarian cyst can pose a risk of hypovolemic shock. [28]

Morbidity

Benign cysts can cause pain and discomfort related to pressure on adjacent structures, torsion, rupture, and hemorrhage (within and outside of the cyst). Morbidity also includes menorrhagia, an increased intermenstrual interval, dysmenorrhea, pelvic discomfort, and abdominal distention. Benign cysts rarely cause death.

Mucinous cystadenomas may cause a relentless collection of mucinous fluid within the abdomen, known as pseudomyxoma peritonei, which may be fatal without extensive treatment.

Approximately 3% of theca lutein cysts are complicated by torsion or hemorrhage, and approximately 30% of these cysts can cause maternal androgen excess. [13] Follicular cysts can cause excess estradiol production, leading to metrorrhagia and menorrhagia.

Ovarian cysts, and more specifically corpus luteal cysts, can rupture, causing hemoperitoneum, hypotension, and peritonitis. This can be exacerbated in women with bleeding dyscrasias, such as those with von Willebrand disease and those receiving anticoagulation therapy.

Ovarian torsion can complicate ovarian cysts and can result in ovarian infarction, necrosis, infertility, premature ovarian menopause, and preterm labor. [14]

Malignant ovarian cystic tumors can cause severe morbidity, including the following:

-

Pain

-

Abdominal distension

-

Bowel obstruction

-

Nausea

-

Vomiting

-

Early satiety

-

Wasting

-

Cachexia

-

Indigestion

-

Heartburn

-

Abnormal uterine bleeding

-

Deep venous thrombosis

-

Dyspnea

Cystic granulosa cell tumors may secrete estrogen, leading to postmenopausal bleeding and precocious puberty in elderly patients and young patients, respectively.

In addition to the normal complications of cysts, the presence of cysts in pregnancy may cause obstructed labor.

-

A multilocular right ovarian cyst that is 24 cm in diameter. It is seen with the adjacent fallopian tube and uterus. The infundibulo-pelvic ligament carrying the ovarian artery and vein has been divided. Histology reported a mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of low malignant potential. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

-

Transabdominal sonogram of a multilocular right ovarian cyst that is 24 cm in diameter, with the adjacent fallopian tube and uterus. The infundibulo-pelvic ligament carrying the ovarian artery and vein has been divided. This sonogram demonstrates a large, complex cystic mass with vascularity within the septations. Red and blue colors show blood flow towards and away from the transducer. The resistive index was low. Histology reported a mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of low malignant potential. Courtesy Patrick O'Kane, MD.

-

A multilocular right ovarian cyst that is 24 cm in diameter has been removed and cut open. It has a smooth surface and a multicystic internal structure. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

-

An ovarian cyst that underwent torsion (twisting of the vascular pedicle). The patient presented with a short history of severe lower abdominal pain. The twisted pedicle can be seen attached to the cyst, which has turned dusky due to ischemia. No viable epithelial lining was available for histologic diagnosis. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

-

Endovaginal sonogram shows a striking echogenic mass lateral to the uterus, with posterior acoustic shadowing giving a "tip-of-the-iceberg" appearance. This is pathognomonic for a dermoid cyst. Occasionally, this appearance may be mistaken for a gas-filled bowel. Courtesy of Patrick O'Kane, MD.

-

A dermoid cyst (mature cystic teratoma) after opening the abdomen. Note the yellowish color of the contents seen through the wall. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

-

A dermoid cyst has been opened in the operating room to reveal copious sebaceous fluid. This cyst also contained hair. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

-

A dermoid cyst has been opened and contains teeth. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

-

Theca-lutein cysts replacing an ovary in a patient with a molar pregnancy. Despite their size these cysts are benign and usually resolve after treatment of the underlying disease. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.

-

Cross-section of a clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Note the cystic spaces intermingled with solid areas. Image courtesy of C. William Helm, MBBChir.