Background

Hypothermia describes a state in which the body's mechanism for temperature regulation is overwhelmed in the face of a cold stressor. Hypothermia is classified as accidental or intentional, primary or secondary, and by the degree of hypothermia.

Accidental hypothermia generally results from unanticipated exposure in an inadequately prepared person; examples include inadequate shelter for a homeless person, someone caught in a winter storm or motor vehicle accident, or an outdoor sport enthusiast caught off guard by the elements. Intentional hypothermia is an induced state generally directed at neuroprotection after an at-risk situation (usually after cardiac arrest, see Therapeutic Hypothermia). [1] Primary hypothermia is due to environmental exposure, with no underlying medical condition causing disruption of temperature regulation. [2] Secondary hypothermia is low body temperature resulting from a medical illness lowering the temperature set-point.

Many patients have recovered from severe hypothermia, so early recognition and prompt initiation of optimal treatment is paramount. See Treating Hypothermia: What You Need to Know, a Critical Images slideshow, to help recognize the signs of hypothermia as well as the best approach for hypothermic patients.

Systemic hypothermia may also be accompanied by localized cold injury (see Emergent Management of Frostbite). See the image below.

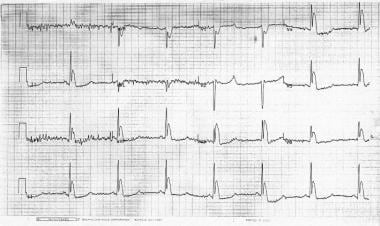

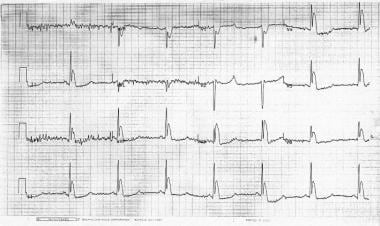

Osborne (J) waves (V3) in a patient with a rectal core temperature of 26.7°C (80.1°F). ECG courtesy of Heather Murphy-Lavoie of Charity Hospital, New Orleans.

Osborne (J) waves (V3) in a patient with a rectal core temperature of 26.7°C (80.1°F). ECG courtesy of Heather Murphy-Lavoie of Charity Hospital, New Orleans.

Pathophysiology

The body's core temperature is tightly regulated in the "thermoneutral zone" between 36.5°C and 37.5°C, outside of which thermoregulatory responses are usually activated. The body maintains a stable core temperature through balancing heat production and heat loss. At rest, humans produce 40-60 kilocalories (kcal) of heat per square meter of body surface area through generation by cellular metabolism, most prominently in the liver and the heart. Heat production increases with striated muscle contraction; shivering increases the rate of heat production 2-5 times.

Heat loss occurs via several mechanisms, the most significant of which, under cold and dry conditions, is radiation (55-65% of heat loss). Conduction and convection account for about 15% of additional heat loss, and respiration and evaporation account for the remainder. Conductive and convective heat loss, or direct transfer of heat to another object or circulating air, respectively, are the most common causes of accidental hypothermia. Conduction is a particularly significant mechanism of heat loss in drowning/immersion accidents as thermal conductivity of water is up to 30 times that of air.

The hypothalamus controls thermoregulation via increased heat conservation (peripheral vasoconstriction and behavior responses) and heat production (shivering and increasing levels of thyroxine and epinephrine). Alterations of the CNS may impair these mechanisms. The threshold for shivering is 1 degree lower than that of vasoconstriction and is considered a last resort mechanism by the body to maintain temperature. [3] The mechanisms for heat preservation may be overwhelmed in the face of cold stress and core temperature can drop secondary to fatigue or glycogen depletion.

Hypothermia affects virtually all organ systems. Perhaps the most significant effects are seen in the cardiovascular system and the CNS. Hypothermia results in decreased depolarization of cardiac pacemaker cells, causing bradycardia. Since this bradycardia is not vagally mediated, it can be refractory to standard therapies such as atropine. Mean arterial pressure and cardiac output decrease, and an electrocardiogram (ECG) may show characteristic J or Osborne waves (see the image below). While generally associated with hypothermia, the J wave may be a normal variant and is seen occasionally in sepsis and myocardial ischemia.

Osborne (J) waves (V3) in a patient with a rectal core temperature of 26.7°C (80.1°F). ECG courtesy of Heather Murphy-Lavoie of Charity Hospital, New Orleans.

Osborne (J) waves (V3) in a patient with a rectal core temperature of 26.7°C (80.1°F). ECG courtesy of Heather Murphy-Lavoie of Charity Hospital, New Orleans.

Atrial and ventricular arrhythmias can result from hypothermia; asystole and ventricular fibrillation have been noted to begin spontaneously at core temperatures below 25-28°C.

Hypothermia progressively depresses the CNS, decreasing CNS metabolism in a linear fashion as the core temperature drops. At core temperatures less than 33°C, brain electrical activity becomes abnormal; between 19°C and 20°C, an electroencephalogram (EEG) may appear consistent with brain death. Tissues have decreased oxygen consumption at lower temperatures; it is not clear whether this is due to decreases in metabolic rate at lower temperatures or a greater hemoglobin affinity for oxygen coupled with impaired oxygen extraction of hypothermic tissues.

The term "core temperature after drop" refers to a further decrease in core temperature and associated clinical deterioration of a patient after rewarming has been initiated. The current theory of this documented phenomenon is that as peripheral tissues are warmed, vasodilation allows cooler blood in the extremities to circulate back into the body core. Other mechanisms may be in operation as well. Some believe that after drop is most likely to occur in patients with frostbite or long-standing hypothermia.

Etiology

Decreased heat production

Several etiologies related to endocrine derangements may cause decreased heat production. These include hypopituitarism, hypoadrenalism, and hypothyroidism. Consider all these conditions in patients presenting with unexplained hypothermia who fail to rewarm with standard therapy.

Other causes include severe malnutrition or hypoglycemia and neuromuscular inefficiencies seen in the extremes of age.

Increased heat loss

This category includes accidental hypothermia due to both immersion etiologies and nonimmersion etiologies and is the most common form of hypothermia encountered in the emergency department.

Patients may present with induced vasodilatation from pharmacologic or toxicologic agents.

Hypothermia due to increased heat loss can occur in conditions with erythroderma, such as burns or psoriasis, which decrease the body's ability to preserve heat. In addition, iatrogenic etiologies, such as cold infusions, overenthusiastic treatment of heatstroke, or emergency deliveries, may cause hypothermia due to increased heat loss.

Impaired thermoregulation

A variety of causes may be associated with impaired thermoregulation, but, generally, it is associated with failure of the hypothalamus to regulate core body temperature.

This may occur with CNS trauma, strokes, toxicologic and metabolic derangements, intracranial bleeding, Parkinson disease, CNS tumors, Wernicke disease, and multiple sclerosis.

Other causes

Miscellaneous causes include sepsis, multiple trauma, pancreatitis, prolonged cardiac arrest, and uremia.

Hypothermia may be related to drug administration; such medications include beta-blockers, clonidine, meperidine, neuroleptics, and general anesthetic agents. Ethanol, phenothiazines, and sedative-hypnotics also reduce the body’s ability to respond to low ambient temperatures.

Epidemiology

US frequency

Accurately estimating the incidence of hypothermia is impossible, as hospital encounters only represent the "tip of the iceberg" in that they reflect the more severe cases. Even so, the number of emergency department encounters for hypothermia is growing, as ever-growing numbers of people take to the outdoors in search of adventure. Hypothermia is also a disease of urban settings. Societal problems with alcoholism, mental illness, and homelessness create a steady stream of these cases to inner-city hospitals. Although most cases occur in regions of the country with severe winter weather, other areas with milder climates also experience cases on a regular basis. This is especially true in milder climates that experience rapid climate changes either due to seasonal changes or day-to-night changes secondary to altitude. According to current data, states with the highest overall death rates for hypothermia are Alaska, New Mexico, North Dakota, and Montana.

The greatest number of cases of hypothermia occur in an urban setting and are related to environmental exposure attributed to alcoholism, illicit drug use, or mental illness, often exacerbated by concurrent homelessness. This is simply due to the fact that more people are found in the urban regions rather than rural areas.

A second affected group includes people in an outdoor setting for work or pleasure, including hunters, skiers, climbers, boaters/rafters, and swimmers.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report the following statistics for deaths by excessive natural cold in the period 1999-2011 [4] :

-

Total deaths: 16,911

-

Average deaths per year: 1,301

-

Highest yearly total: 1,536 (2010)

-

Lowest yearly total: 1,058 (2006)

-

Approximately 67% were among males

The CDC reported the following data from 2019 for death rates attributed to excessive cold or hypothermia in people aged 15 years or older [5] :

-

Higher rates in rural areas compared with urban areas

-

Lowest rates among those aged 15-34 years (0.2 case and 0.5 case per 100,000 population in urban and rural areas, respectively)

-

Increased rates by age, with highest rates among those aged 85 years or older (4.6 in urban areas, 8.6 in rural areas)

Sex

The overall mortality rate from hypothermia is similar between men and women. Because of a higher incidence of exposure among males, men account for 65% of hypothermia-related deaths. A 10-year retrospective study of hypothermia-related deaths in New York City and Houston reported that in both cities, males were more likely to die of hypothermia compared with females. [6]

Age

Very young and elderly persons are at increased risk and may present to the emergency department with symptoms that are not clinically obvious or specific for hypothermia, such as altered mental status.

Older patients appear to be more likely to present with chronic or secondary hypothermia. Half of the recorded deaths from accidental hypothermia occurred in individuals older than 65 years.

Prognosis

The risk of morbidity and mortality depends on the severity of the degree of hypothermia and the underlying cause. Recovery is usually complete for previously healthy individuals with mild or moderate hypothermia (mortality rate < 5%). The mortality rate for patients with severe hypothermia, especially with preexisting illness, may be higher than 50%.

Mortality/morbidity

According to one study, overall in-patient mortality in hypothermic patients was 12%. Most people tolerate mild hypothermia (32-35°C body temperature) fairly well, which is not associated with significant morbidity or mortality. In contrast, a multicenter survey found a 21% mortality rate for patients with moderate hypothermia (28-32°C body temperature). Mortality is even higher in severe hypothermia (core temperature below 28°C). Despite hospital-based treatment, mortality from moderate or severe hypothermia approaches 40%. Patients experiencing concurrent infection account for most deaths due to hypothermia. Other comorbidities associated with higher mortality rates include homelessness, alcoholism, psychiatric disease, and advanced age.

"Indoor hypothermia" is more likely to occur in patients with significant medical comorbidities (alcoholism, sepsis, hypothyroidism/hypopituitarism) and tends to carry worse outcomes than exposure hypothermia.

According to current records, approximately 700 people die in the United States from accidental primary hypothermia each year.

From 1979 to 2016, the death rate as a direct result of exposure to cold ranged from 1-2.5 deaths per million population. [7] According to death certificates, more than 19,000 Americans have died from cold-related causes since 1979.

Patient Education

For patient education resources, see the First Aid and Injuries Center. Also, see the patient education article Hypothermia.

-

Osborne (J) waves (V3) in a patient with a rectal core temperature of 26.7°C (80.1°F). ECG courtesy of Heather Murphy-Lavoie of Charity Hospital, New Orleans.