Practice Essentials

Malignant external otitis (MEO) is an infection that affects the external auditory canal and temporal bone. The causative organism is usually Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and the disease commonly manifests in elderly patients with diabetes. The infection begins as an external otitis that progresses into an osteomyelitis of the temporal bone. Spread of the disease outside the external auditory canal occurs through the fissures of Santorini and the osseocartilaginous junction. [1, 2]

Toulmouche was probably the first physician to report a case of malignant external otitis (MEO), in 1838. In 1959, Meltzer reported a case of pseudomonal osteomyelitis of the temporal bone. In 1968, Chandler discussed the clinical characteristics of malignant external otitis (MEO) and defined it as a distinct clinical disease. [3] He described this external otitis as malignant because he observed an aggressive clinical behavior, poor treatment outcome, and a high mortality rate for the patients affected by this disease.

The subsequent development of effective antibiotics for treating pseudomonal infections has improved the treatment outcomes for patients with malignant external otitis (MEO). Thus, some physicians have suggested that the term malignant should be abandoned in order to provide a more accurate description of the disease process.

Signs and symptoms of malignant otitis externa

Inflammatory changes are observed in the external auditory canal and the periauricular soft tissue.

The pain is out of proportion to the physical examination findings. Marked tenderness is present in the soft tissue between the mandibular ramus and mastoid tip. Granulation tissue is present at the floor of the osseocartilaginous junction. This finding is virtually pathognomonic of malignant external otitis (MEO). Otoscopic examination may also reveal exposed bone.

Other signs and symptoms include the following:

-

Diabetes (90%) or immunosuppression (illness or treatment related)

-

Severe, unrelenting, deep-seated otalgia

-

Temporal headaches

-

Purulent otorrhea

-

Possibly dysphagia, hoarseness, and/or facial nerve dysfunction

Diagnosis and management of malignant otitis externa

The leukocyte count in malignant external otitis (MEO) is usually normal or mildly elevated. A left shift is not commonly found. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is invariably elevated, with an average of 87 mm/h.

Patients with known diabetes need an evaluation of the serum chemistry to determine if the infection is affecting their baseline glucose intolerance. Patients without a history of diabetes should be tested for glucose intolerance.

Culture from the ear drainage should be performed ideally before antimicrobial therapy is initiated. As mentioned, the most common causative organism is P aeruginosa (95%).

Imaging studies are important for determining the presence of osteomyelitis, the extent of disease, and response to therapy. They include technetium Tc 99 methylene diphosphonate bone scanning, gallium citrate Ga 67 scanning, indium In 111–labeled leukocyte scanning, computed tomography (CT) scanning, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Obtain a biopsy of the external auditory canal to exclude carcinoma or other etiologies.

Treatment for malignant external otitis (MEO) includes meticulous glucose control, aural toilet, systemic and ototopic antimicrobial therapy, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy. [4, 5] Surgery is now reserved for local debridement, removal of bony sequestrum, and abscess drainage.

Pathophysiology

Malignant external otitis (MEO) is an infection that affects the external auditory canal and temporal bone. The causative organism is usually Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and the disease commonly manifests in elderly patients with diabetes. The infection begins as an external otitis that progresses into an osteomyelitis of the temporal bone. Spread of the disease outside the external auditory canal occurs through the fissures of Santorini and the osseocartilaginous junction. [1]

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

Malignant external otitis (MEO) is more common in humid and warm climates than in other climates.

Mortality/Morbidity

Cranial neuropathy

Cranial nerves can be affected by inflammation along the skull base or by a neurotoxin produced by Pseudomonas species. The facial nerve (VII) is affected most commonly, usually at the stylomastoid foramen. As the disease progresses, cranial nerves IX, X, and XI can be affected at the jugular foramen, followed by XII at the hypoglossal canal. Cranial nerves V and VI can be affected if the disease extends to the petrous apex.

In 1977, Chandler reported a 32% incidence of facial nerve paralysis. [6] The incidence of facial nerve paralysis appears to have decreased with the development of more effective medical therapy as shown by Franco-Vidal et al who reported a 20% incidence of facial nerve paralysis in 46 treated patients. [7] The other cranial nerves are affected less frequently than the seventh cranial nerve. The development of cranial neuropathy generally was thought to reflect advanced-stage disease associated with a worse prognosis. More recently, Corey et al, Soudry et al, and Mani et al suggested that the presence of facial nerve paralysis does not worsen the prognosis. [8, 9] Recovery of facial nerve function is poor and unpredictable, and should not be used as an indicator of successful treatment. Other cranial nerves that are affected have a higher rate of recovery.

Intracranial complications

These complications rarely occur in the absence of cranial nerve palsies. Meningitis, brain abscess, and dural sinus thrombosis may ensue. Cranial neuropathies related to the jugular foramen should raise concern for sigmoid sinus thrombosis. Cavernous sinus thrombosis should be considered if cranial nerves V or VI are affected. Intracranial complications reflect severe disease and are commonly fatal.

Comorbid conditions

Patients with malignant external otitis (MEO) almost always have diabetes, often with other multiple medical problems. [10] During the course of therapy, Chandler found some deaths related to pneumonia, uremia, myocardial infarction, strokes, and liver failure. Franco-Vidal showed that patients with systemic immunodeficiencies had a worse prognosis. [7]

A nationwide, population-based case-control study from Taiwan, by Yang et al, supported the association between diabetes and malignant external otitis (MEO). The investigators reported that 54.8% of patients with MEO had previously diagnosed diabetes, compared with 13.9% of controls. The adjusted odds ratio for previously diagnosed diabetes in the presence of MEO was 10.07. [11]

A study by Sylvester et al analyzing 8300 cases of inpatient malignant external otitis from the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample database (2002-2013) found that diabetes mellitus in adult and elderly patients was associated with a greater number of comorbidities, longer hospitalizations (5.5 days vs 4.0 days in patients without diabetes), and higher hospital charges ($25,118 vs $17,039 in patients without diabetes). However, in-hospital mortality rates were not significantly greater in patients with diabetes than in those without it (0.6% vs 0.5%, respectively). [12]

A retrospective study by Peled et al of patients with malignant external otitis (MEO), over 90% of whom had diabetes mellitus, looked at the effects of glycemic control in MEO. The investigators found that higher hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels were associated with longer hospital stays, the concentration being 7.6% in patients who where hospitalized for less than 20 days, and 8.7% in those who were hospitalized for 20 days or more. Moreover, while P aeruginosa was found in 26.7% of patients with a mean blood glucose level of 140 mg/dL or lower, the bacterial species existed in 51.0% of those with a higher mean concentration; however, disease outcome was not affected by the glucose level. [13]

Sex

Malignant external otitis (MEO) is more common in males than in females.

Age

Malignant external otitis (MEO) has been reported in all age groups but is most common in patients who are elderly (age, >60 y).

-

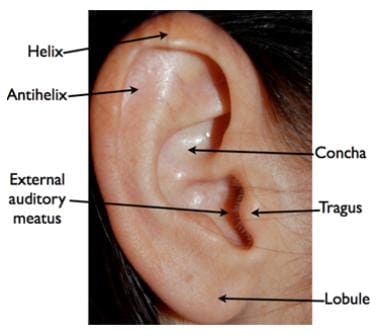

Anatomy of the ear.