Practice Essentials

Fractures of the mandibular body may be classified by anatomic location, condition, and position of teeth relative to the fracture, favorableness, or type. Angle fractures occur in a triangular region between the anterior border of the masseter and the posterosuperior insertion of the masseter. These fractures are distal to the third molar.

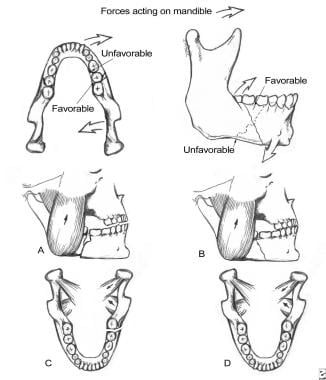

Mandible fractures are also described by the relationship between the direction of the fracture line and the effect of muscle distraction on fracture fragments. Mandible fractures are favorable when muscles tend to draw bony fragments together and unfavorable when bony fragments are displaced by muscle forces. Vertically unfavorable fractures allow distraction of fracture segments in a horizontal direction. These fractures tend to occur in the body or symphysis-parasymphysis area. Horizontally unfavorable fractures allow displacement of segments in the vertical plane.

Angle fractures are often unfavorable because of the actions of the masseter, temporalis, and medial pterygoid muscles, which distract the proximal segment superomedially. Recent evidence evaluating the favorability of angle fractures shows that there is no need to apply different treatment modalities to mandibular fractures regardless of whether the factures are favorable. [1]

The image below depicts the vertical and horizontal forces acting on the mandible, as well as the relationship of muscle pull to fracture angulation.

Forces acting on the mandible and the relationship between muscle pulls and fracture angulation. A: Horizontally unfavorable. B: Horizontally favorable. C: Vertically unfavorable. D: Vertically favorable.

Forces acting on the mandible and the relationship between muscle pulls and fracture angulation. A: Horizontally unfavorable. B: Horizontally favorable. C: Vertically unfavorable. D: Vertically favorable.

For patient education resources, see the Breaks, Fractures, and Dislocations Center, as well as Broken Jaw.

Signs and symptoms of mandibular angle fractures

Patients with a mandibular angle fracture may exhibit the following:

-

Change in occlusion

-

Posttraumatic premature posterior dental contact (anterior open bite) and retrognathic occlusion

-

Anesthesia, paresthesia, or dysesthesia of the lower lip

-

Change in facial contour or loss of external mandibular form

-

Pain, swelling, redness, and localized calor - Signs of inflammation evident in primary trauma

Workup in mandibular angle fractures

The single most informative radiologic study used in diagnosing mandibular fractures is the panoramic radiograph.

Plain films, including lateral-oblique, occlusal, posteroanterior, and periapical views, may also be helpful, as may computed tomography (CT) scanning.

Management of mandibular angle fractures

Patients with isolated nondisplaced or minimally displaced condylar fractures may be treated with analgesics, soft diet, and close observation. Patients with coronoid process fractures may be similarly treated. Additionally, these patients may require mandibular exercises to prevent trismus.

The techniques for closed reduction and fixation of the dentulous mandible vary. Placement of Ivy loops using 24-gauge wire between two stable teeth, with employment of a smaller-gauge wire to provide maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) between Ivy loops, has been successful. Arch bars with 24- and 26-gauge wires are versatile and frequently are used. In an edentulous mandible, dentures can be wired to the jaw with circummandibular wires. The maxillary denture can be screwed to the palate. (Any screw from the maxillofacial set can be used as a lag screw.) Arch bars can be placed and intermaxillary fixation (IMF) achieved. Gunning splints have also been used in this scenario because they provide fixation and yet permit food intake. In cases of comminuted fractures, a mandibular reconstruction plate may be required to restore anatomic position and function.

Multiple approaches for open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) exist. The intraoral approach is typically used in fractures that are nondisplaced or only slightly displaced. External incisions are usually necessary with fractures that have a high degree of dislocation or with comminuted fractures.

Problem

The angle of the mandible is the triangular region bounded by the anterior border of the masseter muscle to the posterior and superior attachment of the masseter muscle (usually distal to the third molar). This area may become fractured secondary to vehicular accidents, assaults, falls, sporting accidents, and other miscellaneous causes.

Epidemiology

Frequency

In general, incidences of fractures of the mandibular body, condyle, and angle are relatively similar, while fractures of the ramus and coronoid process are rare. [2] The literature suggests the following mean frequency percentages based on location:

-

Body - 29%

-

Condyle - 26%

-

Angle - 25%

-

Symphysis - 17%

-

Ramus - 4%

-

Coronoid process - 1%

The mandible is involved in 70% of patients with facial fractures. The number of mandible fractures per patient ranges from 1.5-1.8. Approximately 50% of patients with a mandible fracture have more than 1 fracture.

In a series of 136 patients with angle fractures, 40% had fractures exclusive to the angle, while 60% had multiple fractures that included an angle fracture.

The mandible fracture patterns of a suburban trauma center found that violent crimes such as assault and gunshot wounds accounted for most fractures (50%), while motor vehicle accidents were less likely (29%).

Etiology

Vehicular accidents and assaults are the primary causes of mandibular fractures throughout the world.

Data from industrialized nations suggest that mandible fractures have various causes as follows:

-

Vehicular accidents - 43%

-

Assaults - 34%

-

Work-related causes - 7%

-

Falls - 7%

-

Sporting accidents - 4%

-

Miscellaneous causes - 5%

Assault most often causes mandible angle fractures. This was supported by a multicenter European study by Brucoli et al of 1162 patients, which found that angle fractures most frequently resulted from assaults and falls. It was also reported that assaults were more likely to bring about left-sided angle fractures and that a link existed between assaults and voluptuary habits, a younger mean age, and male gender. Moreover, the study indicated that that the presence of a third molar significantly correlates with an isolated angle fracture diagnosis, with the investigators suggesting that this molar allows complete force dispersal, permitting a weak point to be found upon force impact. [3]

Similarly, an evidence-based study involving 3002 patients with mandibular fractures found that the presence of a lower third molar may double the risk of an angle fracture of the mandible. Another study compared fractures with wisdom teeth to those without and found an increased infectious risk (16.6%) in fractures with wisdom teeth compared with 9.5% risk in fractures without wisdom teeth.

Pathophysiology

Optimal mandible function requires maintenance of normal anatomic shape and stiffness (ie, resistance to deformation under load). Normal occlusion can be defined when the mesiolabial cusp of the maxillary first molar approximates the buccal groove of the mandibular first molar. Fractures result secondary to mechanical overload. Torque results in spiral fractures; avulsion, in transverse fractures; bending, in short oblique fractures; and compression, in impaction and comminution.

Degree of fragmentation depends upon energy transfer as a result of overload. Therefore, wedge and multifragmentary fractures are associated with higher energy release.

Presentation

History

Obtain a thorough history specific to preexisting systemic bone disease, neoplasia, arthritis, collagen vascular disorders, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction.

Knowledge of the type and direction of the causative traumatic force helps determine the nature of injury. For example, motor vehicle accidents (MVAs) have a larger associated magnitude of force than assaults. As a result, a patient who has experienced an MVA most often sustains multiple, compound, comminuted mandibular fractures, whereas a patient hit by a fist may sustain a single, simple, nondisplaced fracture.

Knowing the direction of force and the object associated with the fracture also assists the clinician in suspecting and diagnosing additional fractures.

Physical examination

Pertinent physical findings are limited to the injury site.

Change in occlusion may be evident on physical examination. Any change is highly suggestive of mandibular fracture. Ask the patient to compare postinjury and preinjury occlusion.

Posttraumatic premature posterior dental contact (anterior open bite) and retrognathic occlusion may result from a mandibular angle fracture. Unilateral open bite deformity is associated with a unilateral angle fracture.

Anesthesia, paresthesia, or dysesthesia of the lower lip may be evident. Most nondisplaced mandible fractures are not associated with changes in lower lip sensation; however, displaced fractures distal to the mandibular foramen (in the distribution of the inferior alveolar nerve) may exhibit these findings.

Change in facial contour or loss of external mandibular form may indicate mandibular fracture. An angle fracture may cause the lateral aspect of the face to appear flattened. Loss of the mandibular angle on palpation may be because of an unfavorable angle fracture in which the proximal segment rotates superiorly. The anterior face may be displaced forward, causing elongation.

Lacerations, hematoma, and ecchymosis may be associated with mandibular fractures. Their presence should alert the clinician that thorough investigation is necessary to exclude fracture. Do not close facial lacerations before treating underlying fractures except in the case of life-threatening hemorrhage.

Pain, swelling, redness, and localized calor are signs of inflammation evident in primary trauma.

Indications

Use the simplest means possible to reduce and fixate a mandibular fracture. Because open reduction can carry an increased morbidity risk, use closed techniques for the following conditions:

-

Nondisplaced favorable fractures

-

Grossly comminuted fractures

-

Edentulous fractures (using a mandibular prosthesis)

-

Fractures in children with developing dentition

-

Coronoid and condylar fractures

Indications for open reduction include the following:

-

Displaced unfavorable angle, body, or parasymphyseal fractures

-

Multiple facial fractures

-

Bilateral displaced condylar fractures

-

Fractures of an edentulous mandible (with severe displacement of fracture fragments in an effort to reestablish mandible continuity)

Relevant Anatomy

The angle of the mandible is the triangular region bounded by the anterior border of the masseter muscle to the posterior and superior attachment of the masseter muscle (usually distal to the third molar).

Contraindications

Evaluate and monitor the patient's general physical condition prior to treating mandibular fractures.

Any force capable of causing a mandibular fracture may also injure other organ systems. Case reports have documented concurrent posttraumatic thrombotic occlusion of the internal carotid artery and basilar skull fractures.

Bilateral cervical subcutaneous emphysema, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and spleen lacerations have also been associated with mandible fractures after trauma.

Patients should not undergo surgical reduction of mandible fractures until these issues are addressed.

-

A transverse fracture of the mandible angle without displacement. A: Transverse fracture of the right mandible with fixation using miniplates at the superior and inferior borders. B: Postoperative radiograph demonstrating fixation.

-

Forces acting on the mandible and the relationship between muscle pulls and fracture angulation. A: Horizontally unfavorable. B: Horizontally favorable. C: Vertically unfavorable. D: Vertically favorable.

-

Comminuted angular fracture of the left mandible. A: Transverse and longitudinal fractures. B: A lag screw and reconstruction plate used to provide fixation. C: Radiograph depicting fixation.

-

Comminuted fracture of the ascending mandibular ramus. A: A comminuted fracture of the left ascending ramus. B: Reduction using miniplates of the superior aspect of the ascending ramus. C: Bridging of the comminuted area using a reconstruction plate.