Practice Essentials

Bursitis is defined as inflammation of a bursa. Humans have approximately 160 bursae. These are saclike structures between skin and bone or between tendons, ligaments, and bone. The bursae are lined by synovial tissue, which produces fluid that lubricates and reduces friction between these structures.

Bursitis occurs when the synovial lining becomes thickened and produces excessive fluid, leading to localized swelling and pain. [1, 2, 3] The following bursae are most commonly affected:

-

Subacromial

-

Olecranon

-

Trochanteric

-

Prepatellar

-

Infrapatellar

Symptoms of bursitis may include the following:

-

Localized tenderness

-

Pain (aggravated by movement of the specific joint, tendon, or both)

-

Edema

-

Erythema

-

Reduced movement

Routine laboratory blood work is generally not helpful in the diagnosis of noninfectious bursitis but is appropriate when septic bursitis or underlying autoimmune disease is suspected. Aspiration and analysis of bursal fluid should be done to rule out infectious or rheumatic causes and may also be therapeutic.

MRI is usually unnecessary but if needed is very sensitive for identification of bursitis, and can rule out suspected solid tumors and define pathology for possible surgical excision. Ultrasonography is useful for further imaging of the bursa when the diagnosis is uncertain, and can guide diagnostic aspiration or therapeutic injections.

Conservative treatment to reduce inflammation is used for most patients with bursitis and includes the following:

-

Rest

-

Cold and heat treatments

-

Elevation

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

-

Bursal aspiration

-

Intrabursal steroid injections (with or without local anesthetic agents)

Patients with suspected septic bursitis should be treated with antibiotics while awaiting culture results. Surgical excision of bursae may be required as a last resort for chronic or frequently recurrent bursitis.

See the following for discussion of bursitis at specific sites:

For patient education resources, see the Arthritis Center, as well as Bursitis.

Anatomy

Bursae are flattened sacs that serve as protective cushions between bones and overlapping muscles (deep bursae) or between bones and tendons or skin (superficial bursae). These synovial-lined sacs are filled with minimal amounts of fluid to facilitate movement during muscle contraction. Deep bursae (eg, subacromial and iliopsoas bursae) are located in the fascia. Superficial bursae (eg, olecranon and prepatellar bursae) are located in the subcutaneous tissue.

There are two types of bursae: constant and adventitial. Both types can be involved in acute or chronic bursitis. Constant bursae have the following characteristics:

-

They form during embryologic development

-

They are lined with endothelial cells

-

They are located between bones and tendons or skin

-

They contain synovial cells that secrete a lubricating fluid rich in collagen and proteoglycans

Adventitial bursae (eg, those that develop over a bunion or osteochondroma) have the following characteristics:

-

They form later in life in response to repeated trauma or constant friction and pressure

-

They lack endothelial cells

-

They do not contain synovial fluid

All of the approximately 160 bursae in the human body are potentially susceptible to injury. The three upper-extremity bursae that are most commonly affected by bursitis are the subacromial, subscapular, and olecranon bursae. [4]

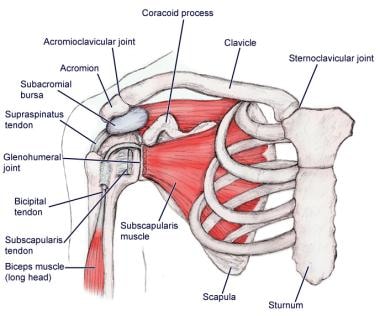

The subacromial bursa separates the superior surface of the supraspinatus tendon from the overlying coracoacromial arch and the deltoid muscle. It lies between the acromion and the rotator cuff and cushions the coracoacromial ligament from the supraspinatus muscle. When the arm is resting at the side, the bursa protrudes laterally from beneath the acromion; when the arm is abducted, it rolls medially beneath the bone. See the image below.

Subscapular bursae are found between the anterior surface of the scapula and the posterior chest wall. The two commonly affected bursae are located superomedially between the serratus anterior and the chest wall. See the image below.

Several olecranon bursae can become inflamed: the superficial olecranon bursa, subtendinous olecranon bursa, or intratendinous olecranon bursa. The former is the most commonly involved as it is more superficial, lying between the attachment of the triceps to the olecranon and the skin.

Various lower-extremity bursae can also be affected by bursitis. The ones most commonly involved are in the hip, the knee, and the ankle. [5, 6, 7]

In the hip, the ischiogluteal bursa lies deep to the gluteus maximus over the ischial tuberosity. The iliopsoas bursa, the largest bursa in the body, lies between the iliopsoas tendon and the lesser trochanter, extending upward into the iliac fossa beneath the iliacus. The trochanteric bursa has superficial and deep components, with the superficial bursa lying between the tensor fascia latae and the skin and the deep bursa located between the greater trochanter and the tensor fasciae latae.

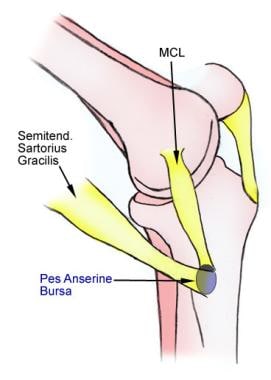

In the knee, the following bursae are commonly affected by bursitis [6] :

-

The medial collateral ligament bursa

-

The anserine (pes anserinus) bursa (see the image below)

-

The prepatellar bursa (located anteriorly over the patella, between patella and skin)

-

The infrapatellar bursa (containing a superficial component lying between the patellar ligament and the skin and a deep component lying between the patellar ligament and the proximal anterior tibia)

-

The popliteal bursae, or Baker cysts (located in the posterior joint capsule of the knee)

In the ankle, two bursae are found at the level of insertion of the Achilles tendon. The superficial one is located between the skin and the tendon, and the deep one is located between the calcaneus and the tendon. The latter is more commonly affected by bursitis. There is also the subcutaneous bursa of the medial malleolus.

Pathophysiology

Inflammation of the bursa causes synovial cells to multiply and thereby increases collagen formation and fluid production. A more permeable capillary membrane allows entrance of high protein fluid. The bursal lining may be replaced by granulation tissue followed by fibrous tissue. The bursa becomes filled with fluid, which is often rich in fibrin, and the fluid can become hemorrhagic. [8] One study suggests that this process may be mediated by cytokines, metalloproteases, and cyclooxygenases.

In septic arthritis, local trauma can inoculate bacteria into the bursa, which triggers the inflammatory process. Hematogenous seeding is less common due to the relatively poor blood supply to the bursae. [9]

There are three phases of bursitis: acute, recurrent, and chronic. [10] During the acute phase of bursitis, local inflammation occurs and the synovial fluid is thickened, and movement becomes painful as a result. Chronic bursitis leads to persistent inflammation with continual pain and can lead to weakening of the overlying ligaments and tendons and, ultimately, rupture of the tendons. Because of the possible adverse effects of chronic bursitis on overlying structures, bursitis and tendinitis may occur together; the differential diagnosis should include both of these diagnoses.

Upper-extremity bursitis

Subacromial bursitis

The subacromial bursa facilitates movement of the supraspinatus tendon and becomes inflamed secondary to repetitive overuse injury of this tendon. Subacromial bursitis is often coexistent with supraspinatus tendinitis and partial- or complete-thickness tears of the supraspinatus tendon (1 of the 4 tendons comprising the rotator cuff). [11]

Subscapular bursitis

Subscapular bursae become inflamed as a result of abnormal bony structures or soft-tissue changes that affect the movement of the scapula over the posterior chest wall.

Olecranon bursitis

The more superficial of the 2 olecranon bursae commonly involved in bursitis is predisposed to direct trauma or cumulative microtrauma from activities requiring frequent elbow motion (eg, swimming, skiing, gymnastics, and weightlifting). This type of bursitis is often recurrent. [12]

Olecranon bursitis, shown here with elbow flexed. Image courtesy of UMDNJ-New Jersey Medical School, www.DoctorFoye.com, and www.TailboneDoctor.com.

Olecranon bursitis, shown here with elbow flexed. Image courtesy of UMDNJ-New Jersey Medical School, www.DoctorFoye.com, and www.TailboneDoctor.com.

Lower-extremity bursitis

Bursitis of hip

Ischiogluteal bursitis is associated with sedentary occupations and is caused by direct stress on the bursa (hence the nickname “weaver’s bottom”). Patients have pain with sitting and walking and have localized tenderness over the ischial tuberosity. Physical examination often reveals pain with passive hip flexion and resisted hip extension.

Iliopsoas bursitis arises when a defect develops in the anterior part of the hip joint capsule, allowing communication of the joint with the bursa. It is often associated with hip pathology (eg, rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis) or recreational injury (eg, running). Infection of the iliopsoas bursa is rare.

Greater trochanter bursitis is common in overweight middle-aged women and is associated with acute trauma, overuse, and mechanical factors. The clinical presentation is of deep, aching lateral hip pain that may radiate into the buttocks or lateral knee. Pain is worse with activity and stretching and may be worse at night, especially when the patient lies on the affected side. Palpation over the greater trochanter elicits severe tenderness. Physical examination reveals pain with resisted hip abduction and external rotation. [13, 14, 15, 16]

Bursitis of knee

The medial collateral ligament bursa is most commonly injured secondary to a twisting injury with external tibial rotation. Medial joint line pain occurs and may limit knee extension. This may be confused with a meniscal tear on physical examination.

Anserine (pes anserinus) bursitis can be caused by trauma, anatomic derangement, overuse, and in association with medial compartmental osteoarthritis. Clinically, patients complain of pain and tenderness over the anteromedial knee that is worse with knee flexion. This condition may be confused with medial meniscal pathology. [17, 18]

Prepatellar bursitis, also known as housemaid’s knee, is associated with trauma or with repetitive kneeling over an extended period. The prepatellar bursa is also a common site for septic (infectious) bursitis, a diagnosis that should be considered when there is skin injury, erythema, warmth, or severe tenderness over the patella. In patients with septic prepatellar bursitis, the patella is not palpable, and knee flexion is painful.

Popliteal bursae (Baker or popliteal cysts) can become enlarged due to degenerative changes of the knee, trauma, soft tissue injuries, or arthritis and are associated with local swelling and pain on walking, jumping, and squatting. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasonography can differentiate an isolated bursitis from intra-articular injury (see also Baker Cyst).

Bursitis of ankle

Retrocalcaneal bursitis can be caused by local trauma from poorly designed shoes, overuse (eg, in athletes), or conditions causing inflammatory arthritis. Patients complain of posterolateral heel pain and may have a posterior heel prominence (known as the Haglund deformity or a “pump bump”), as well as local swelling and tenderness over the Achilles tendon. Pain is increased by squeezing the bursa from side to side and anterior to the Achilles. Rest and ice in the acute period can reduce inflammation, while stretching (eg, physical therapy), a heel lift or open-back shoes can alleviate pressure on the bursa. [19]

Etiology

Bursitis has many causes, including autoimmune disorders, crystal deposition (gout and pseudogout), infectious diseases, traumatic events, and hemorrhagic disorders, as well as being secondary to overuse. Repetitive injury within the bursa results in local vasodilatation and increased vascular permeability, which stimulate the inflammatory cascade. Subdeltoid and subacromial bursitis have been reported after vaccination, when poor technique results in direct injection of the vaccine into the bursa. [20, 21, 22]

The following systemic diseases have also been associated with bursitis:

-

Oxalosis

-

Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy

-

Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome

In addition, generalized hypermobility has been associated with bursitis and other soft-tissue disorders. Some rheumatic conditions, such as gout, can predispose patients to bursitis.

Septic (infectious) bursitis is most common in superficial bursae. In the majority (50-70%) of cases, it results from direct introduction of microorganisms through traumatic injury or through contiguous spread from cellulitis. Less commonly, infection of deep bursae is due to contiguous septic arthritis or bacteremia (10% of cases).

The most common causative organism is Staphylococcus aureus (80% of cases), followed by streptococci. [23, 24] However, many other organisms have been implicated in septic bursitis, including mycobacteria (both tuberculous and nontuberculous strains), fungi (Candida), and algae (Prototheca wickerhamii). [25] There have also been cases of olecranon bursitis from Brucella melitensis. [26]

Factors predisposing to infection include diabetes mellitus, corticosteroid therapy, uremia, alcoholism, skin disease, and trauma, among others. A history of noninfectious inflammation of the bursa also increases the risk of septic bursitis.

Epidemiology and Prognosis

Bursitis accounts for 0.4% of all visits to primary care clinics. The most common locations of bursitis involve the subacromial, olecranon, ischial, trochanteric, and prepatellar bursae.

The incidence of bursitis is higher in athletes, reaching levels as high as 10% in runners. Approximately 85% of cases of septic superficial bursitis occur in men. A French study aimed at assessing the prevalence of knee bursitis in the working population found that most cases occurred in men whose occupations involved heavy workloads and frequent kneeling. [27]

Mortality in patients with bursitis is very low. The prognosis is good, with the vast majority of patients receiving outpatient follow-up and treatment.

A prospective study of 60 patients with trochanteric bursitis found that poor clinical outcomes correlated with obesity, smoking, emotional stress, fibromyalgia, and hypothyroidism. In contrast, better overall physical function was associated with the use of fewer corticosteroid infiltrations, a shorter length of time between symptom onset and surgery, being a nonsmoker, and the absence of prior lumbosacral fusion. [28]

-

Olecranon bursitis, shown here with elbow flexed. Image courtesy of UMDNJ-New Jersey Medical School, www.DoctorFoye.com, and www.TailboneDoctor.com.

-

Olecranon bursitis: aspiration of hemorrhagic effusion. Image courtesy of UMDNJ-New Jersey Medical School, www.DoctorFoye.com, and www.TailboneDoctor.com.

-

Location of anserine (pes anserinus) bursa on medial knee. MCL=medial collateral ligament.

-

Acute infectious bursitis upon presentation to emergency department. Image courtesy of Christopher Kabrhel, MD.

-

Infectious bursitis. Image courtesy of Christopher Kabrhel, MD.

-

Shoulder anatomy muscle, anterior view.