Background

Plague is an acute, contagious, febrile illness usually transmitted to humans by the bite of an infected flea. Plague occurs as 3 major clinical events: bubonic plague, septicemic plague, and pneumonic plague. [1] Human-to-human transmission is ucommon except during epidemics of pneumonic plague. The disease is caused by a coccobacillus-shaped, gram negative bacterium referred to as Yersinia pestis. Yersinia is named in honor of Alexander Yersin, who successfully isolated the bacteria in 1894 during the pandemic that began in China in the 1860s. Plague is most often vector borne, transmitted by fleas, to a variety of rodent populations. The classic vector is the oriental rat flea Xenopsylla cheopis.

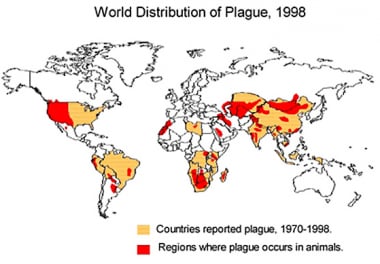

Historically, plague has been known for centuries as being responsible for 3 major pandemics dating back to 430-427 BCE. [1] The second major pandemic was the Black Death dating back to 1347-1351 which was responsible for millions of deaths across Europe. The third originated in China during the 1800’s. With the exception of Antarctica, plague is worldwide in distribution, with most of the human cases reported from developing countries with outbreaks reported regularly.

Three studies have shown that this bacterium emerged from the gut pathogen Yersinia pseudotuberculosis shortly after the first epidemic. [2] Three biovars (with minor genetic variations) have been identified within the Y pestis clone: Antiqua, Medievalis, and Orientalis. [2] One theory is that these biovars emerged before any of the plague epidemics. In fact, as reported by Drancourt et al (2004), genotyping performed on bacteria derived from the remains of plague victims of the first two epidemics revealed sequences similar to that of Orientalis. [3]

Although plague has been considered a disease of the Middle Ages, multiple outbreaks in India and Africa during the last 20 years have stoked fears of another global pandemic. Since the number of human cases has been rising and outbreaks are reappearing in a variety of countries after years of quiescence, the plague is considered a reemerging disease. [4, 5, 6] Recent data pertaining to the period from 2010 through 2019 show that the following countries, from highest to lowest were Madgascar, Congo, Uganda, Peru, Tanzania and United States. These six countries accounted for a total of 4547 cases with 17% mortality (786 deaths). [7]

One reason for plague's reemergence may be global warming, which is ideal for increasing the prevalence of Y pestis in the host population. One study has estimated a more than 50% increase in the plague host prevalence with an increase of 1º C of the temperature in spring. [8] Another reason may be the human population explosion worldwide, which is bringing humans into ever-increasing contact with wildlife. Lastly, the dramatic population increase will contribute to conditions of overcrowding and poor sanitation—conditions ripe for the flourishing of plague hosts and vectors.

Aerosolized Y pestis, causing primary pneumonic plague, has been recognized by bioterrorism experts as having one of the highest potentials as a bioterrorism agent due to its extremely high mortality, its high uptake into enzootic and epizootic animals as well as humans, and its ability to be spread over a large area. It has been classified as a Category A, or high priority, bioterrorism agent by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). [9]

The virulence of this bacterium results from the 32 Y pestis chromosomal genes and two Y pestis –specific plasmids, constituting the only new genetic material acquired since its evolution from its predecessor. [10] These acquired genetic changes have allowed the pathogen to colonize fleas and to use them as vectors for transmission. [4]

Plague is a zoonotic disease that primarily affects rodents; humans are incidental hosts. Dog-to-human transmission was reported in a 2014 outbreak in Colorado. [11] Survival of the bacillus in nature depends on flea-rodent interaction, and human infection does not contribute to the bacteria's persistence in nature. Of the 1500 flea species identified, only 30 of them have been shown to act as vectors of plague. [12] The most prominent of these vectors is Xenopsylla cheopis (oriental rat flea); however, Oropsylla montana has been incriminated as the primary vector for this disease in North America. [13]

Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis), the primary vector of plague, engorged with blood. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Ga.

Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis), the primary vector of plague, engorged with blood. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Ga.

Host fatality has been known to be the harbinger of an epidemic. [12] Whether susceptibility and fatality are related is unknown. However, ground squirrels and prairie dogs have been known to be highly susceptible to plague, whereas others have been known to be either moderately susceptible or absolutely resistant to infection.

The prairie dog is a burrowing rodent of the genus Cynomys. It can harbor fleas infected with Yersinia pestis, the plague bacillus. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Ga.

The prairie dog is a burrowing rodent of the genus Cynomys. It can harbor fleas infected with Yersinia pestis, the plague bacillus. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Ga.

Rock squirrel in extremis coughing blood-streaked sputum related to pneumonic plague. Courtesy of Ken Gage, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Fort Collins, Colo.

Rock squirrel in extremis coughing blood-streaked sputum related to pneumonic plague. Courtesy of Ken Gage, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Fort Collins, Colo.

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

Y pestis is a nonmotile, pleomorphic, gram-negative coccobacillus that is nonsporulating. The bacteria elaborate a lipopolysaccharide endotoxin, coagulase, and a fibrinolysin, which are the principal factors in the pathogenesis of plague. The pathophysiology of plague basically involves two phases—a cycle within the fleas and a cycle within humans.

The key to the organism’s virulence is the phenomenon of "blockage," which aids the transmission of bacteria by fleas. After ingestion of infected blood, the bacteria survive in the midgut of the flea owing to a plasmid-encoded phospholipase D that protects them from digestive enzymes. [14] The bacteria multiply uninhibited in the midgut to form a mass that extends from the stomach proximally into the esophagus through a sphincter-like structure with sharp teeth called the proventriculus.

Pictured is a flea with a blocked proventriculus, which is equivalent to the gastroesophageal region in a human. In nature, this flea would develop a ravenous hunger because of its inability to digest the fibrinoid mass of blood and bacteria. If this flea were to bite a mammal, the proventriculus would be cleared, and thousands of bacteria would be regurgitated into the bite wound. Courtesy of the United States Army Environmental Hygiene Agency.

Pictured is a flea with a blocked proventriculus, which is equivalent to the gastroesophageal region in a human. In nature, this flea would develop a ravenous hunger because of its inability to digest the fibrinoid mass of blood and bacteria. If this flea were to bite a mammal, the proventriculus would be cleared, and thousands of bacteria would be regurgitated into the bite wound. Courtesy of the United States Army Environmental Hygiene Agency.

It has been shown that this property requires the presence of hemin-producing genes, which are needed for the formation of a biofilm that permits colonization of the proventriculus. [15] In fact, as described by Jarrett et al (2004), this mutation in hemin genes allows colonization in the midgut without extension to the proventriculus. Consequently, the "blockage phenomenon" does not occur, thereby leading to failure of transmission. [15] This blockage causes the flea to die of starvation and dehydration. [16]

As a desperate measure, the flea then repeatedly tries to obtain a meal by biting a host, managing only to regurgitate the infected mass into host's bloodstream. However, the concept that the flea must be engorged before becoming infectious loses support when trying to explain the rapid rate of spread of disease during a plague epidemic. Studies of vectors such as O montana clearly indicate the redundancy of the aforementioned hypothesis, since this vector does not die of blockage and remains infectious for a long period, unlike its counterpart. [17]

Once the flea bites a susceptible host, the bacilli migrate to the regional lymph nodes, are phagocytosed by polymorphonuclear and mononuclear phagocytes, and multiply intracellularly. Survival and replication within macrophages are probably of greatest importance in early stages of the disease. [18] Involved lymph nodes show dense concentrations of plague bacilli, destruction of the normal architecture, and medullary necrosis. With subsequent lysis of the phagocytes, bacteremia can occur and may lead to invasion of distant organs in the absence of specific therapy.

The following are the modes of plague transmission in humans: [19]

Bites by fleas

Exposure to humans with pneumonic plague

Handling of infected carcasses

Scratches or bites from infected domestic cats

Exposure to aerosols containing plague-causing bacilli

Another potential mode of plague transmission in humans is contact with an infected dog. In 2014, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) laboratory isolated Y pestis in a blood specimen from a hospitalized man with pneumonia. Further investigation found that the man’s dog had recently died with hemoptysis and that 3 other persons who came into contact with the dog had respiratory symptoms and fever. Specimens from the dog and the other three persons showed evidence of acute Y pestis infection. One of the transmissions may have been human to human, which would be the first such reported US case since 1924. [11]

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

Between 2010 and 2015, 39 cases of human plague were reported in the United States, resulting in 5 deaths. [20] About half of human plague cases involve individuals aged 12-45 years, although it can affect people of all ages. The risk is slightly higher in men, probably owing to a higher likelihood of outdoor activities among males, increasing their risk of exposure to vectors. [20]

CDC, Reported Cases of Human Plague - United States, 1970-2018. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA.

CDC, Reported Cases of Human Plague - United States, 1970-2018. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA.

A few natural plague foci are located in the western United States. During the time period of 1970-2018, approximately 15 US states reported at least once case of bubonic plague. [20] From the states of Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah, 49 cases of plague and 3 attributed deaths were reported from 1994-1999. [21] In 2006, 13 plague cases were reported among residents of New Mexico, Colorado, California, and Texas, two of which resulted in death. [22] The largest enzootic plague area is in North America - the southwestern United States and the Pacific coastal area.

On average, 7 cases of human plague are reported annually in the United States, with a range of 1-17 cases per year. [20] Over time, human cases of plague have moved from crowded cities to the rural West. This has paralleled the observed patterns of introduction of exotic plants and animals. [23] The rate of plague in the United States is low, since most of the endemic areas are rural and largely uninhabited, thereby limiting human exposure. In recent years, and with the potential threat for bioterrorism, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has specified Y pestis as a Category A (Tier 1) bioterrorism agent. As reviewed by Ansari et al, 2 historical events, the siege of Caffa in 1346 and the purported release of the plague bacillus in the second Sino-Japanese War and World War II, are cited examples of the effect of the deliberate release of plague into a susceptible population. [1]

Animal reservoirs in America mostly include squirrels, rabbits, and prairie dogs. However, there has been an established role of domestic cats in the transmission of plague since the late 1970s. From 1977-1998, 23 cases of human plague associated with cats were reported from the western states, representing 8% of all reported plague cases during that time. [13] In this scenario, transmission via inhalation was more common than in any other form of plague.

In a study of cat-related plague, mortality was associated with misdiagnosis or delay in treatment. Of the 23 cases from 1977-1998, 5 of 17 bubonic plague cases resulted in death. [13]

In 2014, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) laboratory isolated Y pestis in a blood specimen from a hospitalized man with pneumonia. Further investigation found that the man’s dog had recently died with hemoptysis and that 3 other persons who came into contact with the dog had respiratory symptoms and fever. Specimens from the dog and the other three persons showed evidence of acute Y pestis infection. One of the transmissions may have been human to human, which would be the first such reported US case since 1924. [11]

International

Most cases of plague reported outside of the United States are from developing countries in Africa and Asia. During 1990-1995, a total of 12,998 cases of plague were reported to the World Health Organization (WHO), particularly from countries such as India, Zaire, Peru, Malawi, and Mozambique. The following countries reported more than 100 cases of plague: China, Congo, India, Madagascar, Mozambique, Myanmar, Peru, Tanzania, Uganda, Vietnam, and Zimbabwe. Several foci are located in the semi-arid regions of northeastern Brazil. Outbreaks have been reported from Malawi and Zambia.

The WHO reports that, in 2003, 9 countries reported a total of 2118 plague cases and 182 deaths, 98.7% and 98.9% of which were reported from Africa, respectively. Currently, the 3 most endemic countries are Madagascar, The Democratic Republic of Congo, and Peru. [1]

CDC, Reported Plague Cases by Country, 2013-2018. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA.

CDC, Reported Plague Cases by Country, 2013-2018. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA.

1998 world distribution of plague. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA.

1998 world distribution of plague. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA.

Mortality/Morbidity

The risk of plague-related death depends on the type of plague and whether the infected individual receives appropriate treatment. [4]

The following are the estimated mortality rates associated with the different types of plague:

-

Pneumonic plague - Untreated, 100%; treated, 50%

-

Bubonic plague - Untreated, up to 60%; treated, < 5% when appropriate antibiotics are used

-

Septicemic plague - 20%-25%

Race

In the United States, most cases of plague occur in whites. Native Americans living in endemic areas of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah have a 10-fold greater risk of acquiring the disease than non–Native Americans.

Humans are exposed in the domestic or outdoor environment. Infections in the wild are usually isolated or sporadic, causing infections in Indians, hunters, miners, and tourists in the United States and Brazil.

Sex

Plague has no sexual predilection.

Age

Most cases of plague occur in persons younger than 20 years.

-

1998 world distribution of plague. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA.

-

The prairie dog is a burrowing rodent of the genus Cynomys. It can harbor fleas infected with Yersinia pestis, the plague bacillus. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Ga.

-

Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis), the primary vector of plague, engorged with blood. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Ga.

-

Ulcerated flea bite caused by Yersinia pestis bacteria. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Ga.

-

Swollen lymph glands, termed buboes, are a hallmark finding in bubonic plague. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Ga.

-

Wayson stain showing the characteristic "safety pin" appearance of Yersinia pestis, the plague bacillus. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Ga.

-

Fluorescence antibody positivity is observed as bright, intense green staining around the cell wall of Yersinia pestis, the plague bacillus. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Ga.

-

Histopathology of lung in fatal human plague–fibrinopurulent pneumonia. Image courtesy of Marshall Fox, MD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Ga.

-

Histopathology of lung showing pneumonia with many Yersinia pestis organisms (the plague bacillus) on a Giemsa stain. Image courtesy of Marshall Fox, MD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Ga.

-

Histopathology of spleen in fatal human plague. Image courtesy of Marshall Fox, MD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Ga.

-

Histopathology of lymph node showing medullary necrosis and Yersinia pestis, the plague bacillus. Image courtesy of Marshall Fox, MD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Ga.

-

Histopathology of liver in fatal human plague. Image courtesy of Marshall Fox, MD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Ga.

-

Focal hemorrhages in islet of Langerhans in fatal human plague. Image courtesy of Marshall Fox, MD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Ga.

-

Pictured is a flea with a blocked proventriculus, which is equivalent to the gastroesophageal region in a human. In nature, this flea would develop a ravenous hunger because of its inability to digest the fibrinoid mass of blood and bacteria. If this flea were to bite a mammal, the proventriculus would be cleared, and thousands of bacteria would be regurgitated into the bite wound. Courtesy of the United States Army Environmental Hygiene Agency.

-

After the femoral lymph nodes, the next most commonly involved regions in plague are the inguinal, axillary, and cervical areas. This child has an erythematous, eroded, crusting, necrotic ulcer at the presumed primary inoculation site in the left upper quadrant. This type of lesion is uncommon in patients with plague. The location of the bubo is primarily a function of the region of the body in which an infected flea inoculates plague bacilli. Courtesy of Jack Poland, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Fort Collins, Colo.

-

Ecchymoses at the base of the neck in a girl with plague. The bandage is over the site of a prior bubo aspirate. These lesions are probably the source of the line from the children's nursery rhyme, "ring around the rosy." Courtesy of Jack Poland, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Fort Collins, Colo.

-

Acral necrosis of the nose, the lips, and the fingers and residual ecchymoses over both forearms in a patient recovering from bubonic plague that disseminated to the blood and the lungs. At one time, the patient's entire body was ecchymotic. Reprinted from Textbook of Military Medicine. Washington, DC, US Department of the Army, Office of the Surgeon General, and Borden Institute. 1997:493. Government publication, no copyright on photos.

-

Acral necrosis of the toes and residual ecchymoses over both forearms in a patient recovering from bubonic plague that disseminated to the blood and the lungs. At one time, the patient's entire body was ecchymotic. Reprinted from Textbook of Military Medicine. Washington, DC: US Department of the Army, Office of the Surgeon General, and Borden Institute. 1997:493. Government publication, no copyright on photos.

-

Rock squirrel in extremis coughing blood-streaked sputum related to pneumonic plague. Courtesy of Ken Gage, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Fort Collins, Colo.

-

CDC, Reported Cases of Human Plague - United States, 1970-2018. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA.

-

CDC, Reported Plague Cases by Country, 2013-2018. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA.