Practice Essentials

Cough and cold suppressant and allergy medicines are widely used and favored by medical professionals and parents alike. Because these medications are available over the counter (OTC) and are found in most households, they are frequently implicated in toxic ingestions, particularly in children. Although most of these incidents are unintentional, the number of intentional ingestions is growing, particularly for recreational use. Antihistamines and cough and cold preparations, respectively, rank seventh and twenty-third on the list of substance categories most frequently involved in human exposures in the United States. [1]

The 3 main components of most cough and cold medicines are antihistamines, decongestants, and antitussives. Allergy medications typically contain antihistamines, decongestants, or both. Toxicity caused by first-generation antihistamines is usually due to their anticholinergic rather than their antihistamine properties. While first-generation H1-receptor antagonists are responsible for the vast majority of antihistamine poisonings, the nonsedating H1-receptor antagonists also have been associated with serious toxicity. [2]

The most commonly used oral decongestants include pseudoephedrine and phenylephrine; a third agent, phenylpropanolamine, has been withdrawn from US market. These agents stimulate alpha-adrenergic receptors and cause a sympathomimetic response at toxic doses. The most common antitussive in OTC preparations is dextromethorphan. Many cold medications also contain acetaminophen. For more information on this topic, see Acetaminophen Toxicity.

Most poisonings are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic and do not require specific therapy. However, the clinician may encounter severe intoxications that require prompt recognition and appropriate disposition. Involvement of the regional poison control center, as well as a medical toxicology consultant, if available, may aid in the treatment and follow-up care of these patients, and they should be contacted for all significant ingestions.

Signs and symptoms

Abnormal vital signs may include the following:

-

Hyperthermia

-

Tachypnea

-

Tachycardia

-

Hypertension

Otolaryngologic anticholinergic effects (typical with antihistamine toxicity) include the following:

-

Mydriasis

-

Nasal dryness and stuffiness

-

Eye dryness

-

Mouth and throat dryness

Cardiovascular findings may include the following:

-

Sinus tachycardia

-

Ventricular tachycardia

-

Torsade de pointes

-

Cardiogenic shock

-

Hypertension

Abnormal neurologic findings include the following:

-

Dizziness

-

Ataxia

-

Hyperexcitability

-

Somnolence

-

Seizures

-

Dystonia

-

Dyskinesia

-

Toxic psychosis (anxiety, agitation, hallucination)

-

Intracranial hemorrhage

-

Coma

Gastroenteritis (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting) can occur with the ethanolamine class of antihistamines. Urinary retention is a common anticholinergic adverse effect of the antihistamines. Rhabdomyolysis has been associated with doxylamine overdose, especially if the ingested dose is larger than 20 mg/kg. [3]

Symptoms of central anticholinergic syndrome include the following:

-

Disorientation

-

Agitation

-

Impairment of short-term memory

-

Nonsensical or incoherent speech

-

Meaningless motor activity that includes repetitive picking or grabbing

-

Visual hallucinations may be prominent

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Ordering of drug screens should be decided in coordination with a regional toxicology center because most of these tests are costly and add little to a complete history with a known ingestion. Turn-around time for these tests often is very long; furthermore, screens are not sensitive or specific for many drugs.

An electrolyte panel and a complete blood count are recommended for all cases of possible toxicity. Studies in selected patients are as follows:

-

Plasma creatine kinase and myoglobin, if rhabdomyolysis is suspected secondary to antihistamine/decongestant combination that contains pseudoephedrine or phenylephrine

-

Blood cultures, if the patient is hyperthermic, seriously ill, or the diagnosis of anticholinergic poisoning is questionable

-

Chest radiography, if the patient has severe respiratory or CNS depression

-

Head CT scan, in patients with seizures or altered mental status

-

ECG, especially if tachycardia or bradycardia is present

-

Lumbar puncture, if patient has altered mental status or new-onset seizures in the setting of an unknown toxic exposure

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Emergency department care is as follows:

-

Perform bedside determinations of glucose for patients with altered levels of conscious and treat with intravenous dextrose, if appropriate

-

For hypotensive patients, administer a bolus of normal saline or lactated Ringer solution

-

Administer activated charcoal to patients who are cooperative, have a good gag reflex, and can take liquids by mouth safely

Acute dystonic reactions to antihistamines may be treated with oral or IV diazepam. Seizures can be treated with lorazepam. Physostigmine may be used for refractory seizures, when directed by a regional poison control center or a medical toxicologist

Serotonin syndrome must be managed by addressing each symptom individually. Hyperthermia should be managed by undressing the patient and enhancing evaporative heat loss by keeping the skin damp and using cooling fans. Muscle activity and agitation may be diminished with the use of diazepam.

Rhabdomyolysis

-

Ensure adequate hydration to maintain urine output at 2 mg/kg/h

-

Furosemide or mannitol may be needed to maintain diuresis

-

Consider using a solution of sodium bicarbonate and potassium chloride to alkalinize the urine to a pH of at least 7.5; monitor serum pH to avoid inducing severe alkalemia

-

Chart strict intake and output

-

Consult a nephrologist for oliguria or renal failure, and arrange hemodialysis for the anuric or severely acidotic patient

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Despite the popularity of cough and cold medications, minimal data support their effectiveness. A Cochrane review found no good evidence for or against the effectiveness of OTC medicines in acute cough; in several pediatric studies, antitussives, antihistamines, antihistamine decongestants, and antitussive/bronchodilator combinations were no more effective than placebo. [4]

In 2006, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) found that "literature regarding over-the-counter cough medications does not support the efficacy of such products in the pediatric age group." [5] In 2007, a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advisory committee recommended that the use of OTC cough and cold medications be prohibited in children younger than 6 years. [6, 7]

The FDA took action against unapproved prescription oral cough, cold, and allergy drug products due to concerns about risks, particularly the potential for medication errors because of confusing product names and inappropriate labeling of products for use in children aged 2 years or younger. From 2006-2011 the Unapproved Drugs Initiative led to the FDA removing 1,500 unapproved products. [8, 9]

Pathophysiology

The principal active ingredients in cough and cold medications are antihistamines, decongestants, and antitussives. Allergy medications typically contain antihistamines, decongestants, or both. Many cold medications also contain acetaminophen. For more information on this topic, see Acetaminophen Toxicity.

Antihistamines

Antihistamines comprise a broad class of pharmacologic agents that interact with four types of histamine receptors. H1-receptor antagonists are used for treatment of allergy and colds. These medicines include the first-generation, H1-receptor antagonists (eg, diphenhydramine), which are capable of producing significant central nervous system (CNS) effects; and the newer, second-generation, "nonsedating" H1 blockers (eg, loratadine).

H2-receptor antagonists (eg, cimetidine), work primarily on gastric mucosa, inhibiting gastric secretion. Newer, experimental antihistamines act on presynaptic H3 receptors and the recently discovered H4 receptors. Currently, no H3 or H4 receptor antagonists are commercially available, but several compounds, including conessine; diazepam amides; and diamine, dihydrobenzoxathin, biphenyl sulfonamide, and benzoquinoline derivatives, have been shown to interact with the H3 receptor. [10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]

Modulation of the H3 receptor may have various clinical effects on wakefulness, cognition, and hunger. [16] Phase IIb clinical trials for a wide range of disorders are already under way. [17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26]

H4 receptors have been identified on cells of hematopoietic lineage (dendritic cells, mast cells, eosinophils, basophils, T cells, NK cells). Several ligands have been identified with affinity for this receptor. Modulation may have effects on nociception, inflammation, pruritus, and autoimmune disorders. [27, 28, 29] Phase II clinical trials involving antagonism of the H4 receptor for treatment of asthma, dermatitis, and rhinitis are under way.

The 6 structural classes of H1 antihistamines are as follows:

-

Alkylamines (eg, brompheniramine, chlorpheniramine, dexchlorpheniramine, pheniramine, triprolidine)

-

Ethanolamines (eg, carbinoxamine, clemastine, dimenhydrinate, diphenhydramine, doxylamine)

-

Ethylenediamines (eg, pyrilamine, tripelennamine)

-

Phenothiazines (eg, methdilazine, promethazine, trimeprazine)

-

Piperidines (eg, cyproheptadine, fexofenadine, loratadine)

-

Piperazines (eg, cetirizine, cyclizine, hydroxyzine, levocetirizine, meclizine)

The most commonly used antihistamines in OTC preparations come from the alkylamine (eg, chlorpheniramine, brompheniramine) and ethanolamine (eg, diphenhydramine, clemastine) groups.

All H1 antagonists are reversible, competitive inhibitors of histamine receptors. Some of the first-generation H1-receptor blockers (eg, diphenhydramine, clemastine, promethazine) also have anticholinergic properties.

Histamine is not a major mediator of the common cold, and the benefits of antihistamines in relieving congestion appear to be secondary to their anticholinergic properties. Atropine, the prototype of anticholinergics, and other substances with anticholinergic properties competitively inhibit the muscarinic effect of acetylcholine by blocking its action in the autonomic ganglia and at the neuromuscular junctions of the voluntary muscle system. They affect the peripheral and central autonomic nervous systems.

The anticholinergic properties of antihistamine are also responsible for their toxicity. Anticholinergic toxicity may manifest as follows:

-

Sinus tachycardia

-

Dry skin and mucous membranes

-

Dilated pupils and blurred vision

-

Ileus

-

Urinary retention

-

Central nervous system depression or agitation

-

Hyperactivity or psychosis

H1-receptor blockers may disrupt cortical neurotransmission and block fast sodium channels. These effects can exacerbate sedation, but they also can result in seizure activity. Sodium channel blockade in the cardiac cells can cause conduction delays manifested by widening of the QRS interval and dysrhythmias.

Doxylamine has been associated with rhabdomyolysis. The mechanism of its toxicity is unknown, but doxylamine may have a direct toxic effect on muscle, possibly thorough injury to the sarcolemma. [30]

The first-generation antihistamine cyproheptadine is known to block serotonin receptors, as do the recently discovered compounds that have dual H3 antagonist and serotonin reuptake inhibition properties. [10] The phenothiazine class of antihistamines (eg, promethazine) has alpha-adrenergic blocking activity and may cause hypotension. H1 receptors have been found on sebocytes, and the use of H1 blockers in the management of acne may have a future role. [31]

Fexofenadine, loratadine, desloratadine, astemizole, cetirizine, and levocetirizine are peripherally selective H1-receptor antagonists. Desloratadine is the most potent of these. [32] They have a distinct clinical advantage because they bind much more selectively to peripheral H1 receptors and have a lower binding affinity for the cholinergic and alpha-adrenergic receptor sites than do other antihistamines.

This group of antihistamines is popular because specificity for the peripheral histamine receptor site eliminates many adverse effects, including CNS depression, blurred vision, dry mouth, and tachycardia. These medications are commonly used in the treatment of allergic rhinitis and chronic idiopathic urticaria. [33, 34]

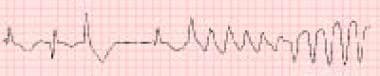

Two nonsedating antihistamines, terfenadine and astemizole, are known to inhibit the potassium rectifier currents (HERG1K), which slows repolarization. This manifests clinically as prolongation of the QT interval and torsade de pointes (see the image below). For that reason, terfenadine and astemizole have been removed from the US market.

Terfenadine is the antihistamine most commonly associated with torsade de pointes in both acute overdose and therapeutic administration.

Terfenadine is the antihistamine most commonly associated with torsade de pointes in both acute overdose and therapeutic administration.

Terfenadine has been replaced by fexofenadine, which is the pharmacologically active metabolite of terfenadine. Only one case has been reported in which a patient taking fexofenadine experienced QT prolongation progressing to ventricular tachycardia and degenerating into ventricular fibrillation. [35] However, this particular individual may have had additional risk factors that may have contributed to or caused that effect. [36, 37]

Levocetirizine, which is the L-enantiomer of cetirizine (cetirizine and levocetirizine are both metabolic derivatives of hydroxyzine) has not been associated with torsade de pointes in volunteer and animal studies.

Diphenhydramine is known to prolong the QT interval. Previously, this effect was presumed to result from inhibition of the delayed potassium rectifier channel, but more recent studies showed that diphenhydramine has a relatively weak affinity for the HERG1K receptor. [38] Torsade de pointes has not been documented with diphenhydramine, most likely because its anticholinergic effect causes sinus tachycardia, which shortens repolarization.

In addition to differences in peripheral versus central binding, the propensity to cause sedation among the various antihistamines may be related to disease process (ie, atopic dermatitis versus allergic rhinitis), receptor internalization after binding, and the interaction of P-glycoprotein (a protein responsible for facilitating transport across various cell membranes and found in many tissues including the blood-brain barrier). [39, 40, 41]

Although the sedative properties of diphenhydramine have led to its use as a hypnotic, paradoxical excitation may occasionally occur. Paradoxical excitation in CYP2D6 ultrarapid metabolizers has been reported with diphenhydramine use. [42]

A new class of selective nonsedating H1 antagonists, the norpiperidine imidazoazepines, is currently in clinical trials. Current in vitro and in vivo safety studies show no increase in incidence of cardiac dysrhythmia. One such agent, bilastine, has demonstrated a favorable profile in animal models in preclinical trials. [43] In 2010, its use was authorized in the European Union for the symptomatic treatment of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and urticaria in adults and children older than 12 years.

Antihistamines are generally well absorbed after ingestion. Therapeutic effects begin within 15-30 minutes and are fully developed within 1 hour. They have varied peak plasma concentrations with a range of 1-5 hours. Antihistamines are capable of inducing the hepatic microsomal enzymes and may enhance their own rate of elimination in patients who use them long term. This phenomenon often is referred to as autoinduction of metabolism.

Decongestants

Decongestants are absorbed readily from the GI tract (except for phenylephrine, because of irregular absorption and first-pass metabolism by the liver) and attain a high concentration in the CNS. Peak plasma concentrations are achieved within 1-2 hours after oral administration. Toxic levels of pseudoephedrine have not been identified.

Pseudoephedrine, phenylephrine, and phenylpropanolamine cause direct presynaptic catecholamine release and may also block catecholamine reuptake and influence enzymes to slow catecholamine breakdown. Blood pressure elevation often is accompanied by a reflex bradycardia caused by the baroreceptors and results in postural hypotension.

Clinical manifestations of decongestant toxicity result from a direct effect on adrenergic receptors in muscles and glands and stimulation of the respiratory center and CNS, and include the following:

-

Bronchodilation

-

Hyperexcitability

-

Restlessness

-

Hallucinations

-

Seizures

-

Psychosis

-

Intracranial bleeding

One case report described cardiomyopathy and left ventricular dysfunction as a result of persistent tachycardia from pseudoephedrine use, with resolution upon its termination. [44] However, a small study in India found no additional dysrhythmia risk from pseudoephedrine use in children with rhinitis. [45]

Phenylpropanolamine has often been implicated in cases of pediatric ingestion, with toxicity starting at 6-10 mg/kg. Toxic effects include seizure, cerebral vasculitis, and kidney failure.

A 2000 study found that phenylpropanolamine was an independent risk factor for hemorrhagic stroke in women aged 18-49 years. This resulted in the removal of phenylpropanolamine from the US OTC market. [46] However, preparations containing this substance may still be in homes and in medications from foreign countries. All household medications should be checked for phenylpropanolamine, and those found to contain it should be discarded.

Antitussives

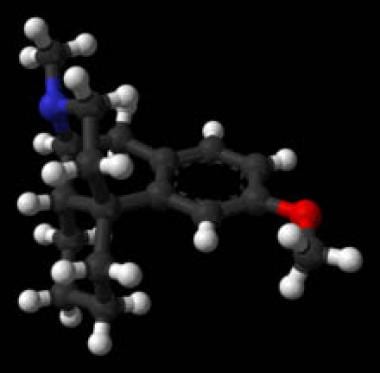

Dextromethorphan, the most common cough suppressant, is the methylated dextro-isomer of levorphanol, a codeine analog. See the image below.

Dextromethorphan is a synthetic opioid that acts at opiate receptors in the CNS but does not have any of the other effects of typical opiates; it has no analgesic and minimal addictive properties. Dextromethorphan has shown agonist activity at the serotonergic transmission, inhibiting the reuptake of serotonin at synapses and causing potential serotonin syndrome, especially when used concomitantly with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).

In addition, dextromethorphan and its primary active metabolite, dextrorphan, which shows similar effects to other N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonists such as phencyclidine (PCP), demonstrate anticonvulsant activity in animals by antagonizing the action of glutamate and are classified as a dissociative medication.

The usefulness of quantitative determination for dextromethorphan is unclear because no correlation exists between blood levels and clinical effects. However, qualitative determination in blood or urine can demonstrate the presence or absence of dextromethorphan. In a pharmacokinetic study, a peak serum concentration of 0.1-0.2 mg/mL was reached after a single 20-mg oral dose in healthy volunteers. Five percent of persons of European ethnicity lack the ability to metabolize the drug normally, leading to toxic levels with smaller doses.

In supra-therapeutic doses, dextromethorphan has psychoactive effects, and this has led to its recreational use in young persons. [47] Effects of dextromethorphan megadoses (5-10 times the recommended dose) are similar to those of phencyclidine (PCP), and include ataxia, abnormal muscle movements, respiratory depression, and dissociative hallucinations. Dextromethorphan can cause false-positive results for PCP in urine toxicologic screening tests.

The half-life of dextromethorphan is short (typical intoxications last 6-8 h); the mainstay of treatment is supportive care. Naloxone has been used with intermittent success to reverse ataxia and respiratory depression.

Codeine is also thought to have antitussive effects and may be prescribed in combination with promethazine. This medication is not recommended for use in the pediatric population. Codeine is an opioid analgesic and is the most commonly ingested opioid, in toxic doses, by children younger than 6 years, as reported by the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC). Doses greater than 5 mg/kg are reported to produce respiratory and CNS depression.

Etiology

Unintentional exposures tend to occur in children younger than 6 years because they are eager to explore their environment and place objects into their mouths. Unintentional ingestion typically represents a smaller dose of the toxic substance, and the child presents to the emergency department soon after ingestion. Unfortunately, as many as 30% of children who experience one ingestion experience a repeat ingestion. In this age group, the possibility of child abuse or neglect should be explored.

Only 47% of reported adolescent ingestions are accidental, others are motivated by suicidal intention or recreational abuse. Both suicidal and recreational ingestion occur with increased frequency in the teenage population, and it may involve multiple substances at higher doses.

Dextromethorphan has been used as a recreational drug by adolescents. Deliberate ingestion of supra-therapeutic doses of dextromethorphan can lead to intoxication with symptoms of euphoria, bizarre behavior, hyperactivity, auditory hallucinations, visual hallucinations, and association of sounds with colors. Slang terms for dextromethorphan include CCC, triple C, DXM, dex, poor man's PCP, skittles, and robo; recreational use of high-dose dextromethorphan is known as robotripping. [47]

Chlorpheniramine is an OTC antihistamine that is usually used in adults. However, the abuse potential of this medication by adolescents has been recently reported. Its effects in deliberate megadosing for intoxication are similar to that of dextromethorphan.

Inappropriate use of antihistamines for upper respiratory infection symptoms and otitis media may unnecessarily expose children to the potential side effects of this class of medication. Furthermore, no study has shown a benefit in the management of these conditions with either antihistamines or decongestants. [48]

Epidemiology

The American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC) reported that in the United States in 2020, antihistamines accounted for 71,456 single case exposures. The majority of exposures (36,200) were in children younger than 6 years. Diphenhydramine is the most common antihistamine exposure, accounting for 40% of cases. Cold and cough preparations accounted for 26,204 single case exposures, with 11,305 in children younger than 6 years. [1]

The peak age for childhood poisoning ranges from 1-3 years. A study of emergency department (ED) visits in children younger than 6 years for ingestions of OTC liquid medications found that diphenhydramine was the second most commonly implicated medication (after acetaminophen), accounting for 1200 annual visits and an estimated 7.4 ED visits per 100,000 bottles sold. [49]

In children younger than 6 years, the vast majority of exposures are unintentional. In the teenage population, both suicidal and recreational ingestion occur with increased frequency, and exposures may involve multiple substances at higher doses.

Data from the AAPCC's National Poison Data System showed that the annual rate of calls involving intentional abuse of dextromethorphan tripled from 2000 to 2006, then plateaued from 2006 to 2015. From 2006 to 2015, the rate in adolescents age 14-17 years decreased by 56.3%, from 143.8 to 80.9 calls per million population. The decrease corresponded to growing public health efforts to curtail the abuse of OTC products that contain dextromethorphan. [50]

Prognosis

The prognosis is affected by the presence of underlying medical conditions, co-ingestions, and the amount of drug ingested. The vast majority of patients recover with supportive care and observation.

Multisystem organ failure and death have resulted from severe antihistamine overdose. Among first-generation antihistamines, mortality from diphenhydramine occurs more than any other agent. In the United States, diphenhydramine is used more commonly than other antihistamines. It also is associated with more cardiotoxicity and a higher incidence of seizures than other first-generation antihistamines. Pheniramine, an antihistamine commonly used in Australia, also is associated with a relatively high incidence of seizures.

Of the 71,456 antihistamine exposures reported to US poison control centers in 2020, 6786 resulted in moderate-to-major toxicity. Eleven deaths were reported, 9 of which were associated with diphenhydramine. [1]

First-generation H1-receptor antagonists, such as diphenhydramine, may be particularly dangerous because they may cause pronounced agitation and seizures, resulting occasionally in rhabdomyolysis and acidosis. Also, a quinidinelike sodium channel blocking effect, and at high doses, a potassium channel blocking effect (HERG1K), may cause delayed conduction (prolonged QRS) and repolarization (prolonged QT) and contribute to ventricular dysrhythmias.

From 1990-2005 the Civil Aerospace Medical Institute (CAMI) reported that antihistamines were found in 338 of 5383 pilot fatalities, and were thought to be a factor in 50 of those cases and the cause in 13 cases. The prevalence of antihistamine use in fatal crashes increased from 4% to 11% over that time span, indicating a worrisome trend that has led to protocols on allowed agents and abstinence time requirements. [51, 52]

Reports of delayed pulmonary edema from antihistamine overdose have been reported. [53] Famotidine has been shown to cause a significant increase in serum phosphate levels in hemodialysis patients taking calcium carbonate (even at the recommended dose of 10 mg/d). [54]

Patient Education

Patient education is an important part of pediatric toxicology. Half of children who ingested a poison do it again within a year. Review poison prevention techniques with parents. [55, 56, 57] Encourage poison proofing of the home and posting local poison control center telephone numbers by telephones throughout the home.

Review medication usage with caregivers. One study showed that only 30% of caregivers who administered acetaminophen were able to demonstrate both accurate measuring and correct dosage for their child.

Parents should be taught the following guidelines to prevent future ingestions:

-

Keep household cleaning products in high locked cabinets rather than under the sink. Safety latches should be place on all kitchen and bathroom cabinets and drawers that contain potentially hazardous substances.

-

Parents should lock all reachable medicine cabinets, always keep medications in their original (childproof) containers and dispose of unused prescriptions by flushing them down the toilet.

-

Medication should be considered "medicine," not a toy or candy. Medicine should never be referred to as candy and, if possible, not administered in front of other children. Parents, relatives, and friends also should childproof their homes.

In the past, parents were advised to have ipecac syrup available at home, to induce vomiting in case of poisoning. However, since 2004 the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology and the European Association of Poison Centres and Clinical Toxicologists have recommended that routine administration of ipecac at the site of ingestion or in the emergency department should definitely be avoided, [58] and the American Academy of Pediatrics currently recommends discarding bottles of ipecac syrup. However, the US Food and Drug Administration continues to permit over-the-counter sale of 1-oz bottles of ipecac syrup, with the warning that it is for use only under medical supervision in the emergency treatment of poisonings. [59]

In instances of recreational abuse, adolescents and their parents should be counseled on the dangers of addiction, as well as the health risks from dextromethorphan, especially in combination with pseudoephedrine, acetaminophen, and antihistamines.

In the 21st century, the use of cough and cold preparations has declined because of increased awareness of their potential toxicity. [60, 61] However, proper labeling and health literacy remain growing issues. [62]

For patient education information, see Poisoning and Poison Proofing Your Home..

-

Dextromethorphan.

-

Terfenadine is the antihistamine most commonly associated with torsade de pointes in both acute overdose and therapeutic administration.