Practice Essentials

Hyperkalemia is defined as a potassium level greater than 5.5 mEq/L. [1] It can be difficult to diagnose clinically because symptoms may be vague or absent. However, the fact that hyperkalemia can lead to sudden death from cardiac arrhythmias requires that physicians be quick to consider hyperkalemia in patients who are at risk for it. [2, 3] Initial emergency department care includes assessment of the ABCs and prompt evaluation of the patient's cardiac status with an electrocardiogram (ECG). In patients in whom hyperkalemia is severe (potassium >7.0 mEq/L) or symptomatic, treatment should commence before diagnostic investigation of the underlying cause.

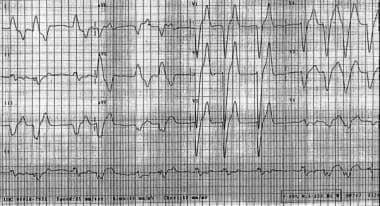

See the ECG below.

See also Can't-Miss ECG Findings, Life-Threatening Conditions: Slideshow, a Critical Images slideshow, to help recognize the conditions shown in various tracings.

Signs and symptoms of hyperkalemia

Patients with hyperkalemia may be asymptomatic, or they may report the following symptoms (cardiac and neurologic symptoms predominate):

-

Generalized fatigue

-

Weakness

-

Paresthesias

-

Paralysis

-

Palpitations

Evaluation of vital signs is essential for determining the patient’s hemodynamic stability and the presence of cardiac arrhythmias related to hyperkalemia. [1] Additional important components of the physical exam may include the following:

-

Cardiac examination may reveal extrasystoles, pauses, or bradycardia

-

Neurologic examination may reveal diminished deep tendon reflexes or decreased motor strength

-

In rare cases, muscular paralysis and hypoventilation may be observed

-

Signs of renal failure, such as edema, skin changes, and dialysis sites, may be present

-

Signs of trauma may indicate that the patient has rhabdomyolysis, which is one cause of hyperkalemia

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis of hyperkalemia

Laboratory studies

The following lab studies can be used in the diagnosis of hyperkalemia:

-

Potassium level: The relationship between serum potassium level and symptoms is not consistent; for example, patients with a chronically elevated potassium level may be asymptomatic at much higher levels than other patients; the rapidity of change in the potassium level influences the symptoms observed at various potassium levels

-

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels: For evaluation of renal status

-

Calcium level: If the patient has renal failure (because hypocalcemia can exacerbate cardiac rhythm disturbances)

-

Glucose level: In patients with diabetes mellitus

-

Digoxin level: If the patient is on a digitalis medication

-

Arterial or venous blood gas: If acidosis is suspected

-

Urinalysis: To look for evidence of glomerulonephritis if signs of renal insufficiency without a known cause are present

-

Cortisol and aldosterone levels: To check for mineralocorticoid deficiency when other causes are eliminated

Electrocardiography

Electrocardiography is essential and may be instrumental in diagnosing hyperkalemia in the appropriate clinical setting. Electrocardiographic changes have a sequential progression that roughly correlates with the patient’s potassium level. Potentially life-threatening arrhythmias, however, can occur without distinct electrocardiographic changes at almost any level of hyperkalemia.

See Workup for more detail.

Management of hyperkalemia

Prehospital care

Prior to reaching the emergency department, treatment of a patient with hyperkalemia includes the following:

-

A patient with known hyperkalemia or a patient with renal failure with suspected hyperkalemia should have intravenous access established and should be placed on a cardiac monitor [4]

-

In the presence of hypotension or marked QRS widening, intravenous bicarbonate, calcium, and insulin given together with 50% dextrose may be appropriate

-

Avoid calcium if digoxin toxicity is suspected; magnesium sulfate (2 g over 5 min) may be used alternatively in the face of digoxin-toxic cardiac arrhythmias

Inhospital care

Once the patient reaches the emergency department, assessment and treatment include the following:

-

Continuous ECG monitoring with frequent vital sign checks: When hyperkalemia is suspected or when laboratory values indicative of hyperkalemia are received

-

Assessment of the ABCs and prompt evaluation of the patient's cardiac status with an electrocardiogram (ECG)

-

Discontinuation of any potassium-sparing drugs or dietary potassium

If the hyperkalemia is known to be severe (potassium >7.0 mEq/L) or if the patient is symptomatic, begin treatment before diagnostic investigation of the underlying cause. Individualize treatment based upon the patient's presentation, potassium level, and ECG.

Dialysis is the definitive therapy in patients with renal failure or in whom pharmacologic therapy is not sufficient. Any patient with significantly elevated potassium levels should undergo dialysis, as pharmacologic therapy alone is not likely to adequately bring down the potassium levels in a timely fashion.

Medications

Drugs used in the treatment of hyperkalemia include the following:

-

Calcium (either gluconate or chloride): Reduces the risk of ventricular fibrillation caused by hyperkalemia

-

Insulin administered with glucose: Facilitates the uptake of glucose into the cell, which results in an intracellular shift of potassium

-

Alkalinizing agents: Increases the pH, which results in a temporary potassium shift from the extracellular to the intracellular environment; these agents enhance the effectiveness of insulin in patients with acidemia

-

Beta2-adrenergic agonists: Promote cellular reuptake of potassium

-

Diuretics: Cause potassium loss through the kidney

-

Binding resins: Promote the exchange of potassium for sodium in the gastrointestinal (GI) system

-

Magnesium sulfate: Has been successfully used to treat acute overdose of slow-release oral potassium

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Hyperkalemia is a potentially life-threatening illness that can be difficult to diagnose because of a paucity of distinctive signs and symptoms. The physician must be quick to consider hyperkalemia in patients who are at risk for this disease process. Because hyperkalemia can lead to sudden death from cardiac arrhythmias, any suggestion of hyperkalemia requires an immediate ECG to ascertain whether electrocardiographic signs of electrolyte imbalance are present.

Pathophysiology

Potassium is a major ion of the body. Nearly 98% of potassium is intracellular, with the concentration gradient maintained by the sodium- and potassium-activated adenosine triphosphatase (Na+/K+ –ATPase) pump. The ratio of intracellular to extracellular potassium is important in determining the cellular membrane potential. Small changes in the extracellular potassium level can have profound effects on the function of the cardiovascular and neuromuscular systems. The normal potassium level is 3.5-5.0 mEq/L, and total body potassium stores are approximately 50 mEq/kg (3500 mEq in a 70-kg person).

Minute-to-minute levels of potassium are controlled by intracellular to extracellular exchange, mostly by the sodium-potassium pump that is controlled by insulin and beta-2 receptors. A balance of GI intake and renal potassium excretion achieves long-term potassium balance.

Hyperkalemia is defined as a potassium level greater than 5.5 mEq/L. [1] Ranges are as follows:

-

5.5-6.0 mEq/L - Mild

-

6.1-7.0 mEq/L - Moderate

-

7.0 mEq/L and greater - Severe

Hyperkalemia results from the following:

-

Decreased or impaired potassium excretion - As observed with acute or chronic renal failure [5] (most common), potassium-sparing diuretics, urinary obstruction, sickle cell disease, Addison disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

-

Additions of potassium into extracellular space - As observed with potassium supplements (eg, PO/IV potassium, salt substitutes), rhabdomyolysis, and hemolysis (eg, blood transfusions, burns, tumor lysis)

-

Transmembrane shifts (ie, shifting potassium from the intracellular to extracellular space) - As observed with acidosis and medication effects (eg, acute digitalis toxicity, beta-blockers, succinylcholine)

-

Fictitious or pseudohyperkalemia - As observed with improper blood collection (eg, ischemic blood draw from venipuncture technique), laboratory error, leukocytosis, and thrombocytosis

Frequency

United States

Hyperkalemia is diagnosed in up to 8% of hospitalized patients. A retrospective study by Betts et al estimated that in 2014, 3.7 million US adults (1.55%) had hyperkalemia, an increase over 2010. Within the adult hyperkalemic population in 2014, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and/or heart failure existed in 48.43%, with the annual prevalence of hyperkalemia in patients with CKD and/or heart failure that year being 6.35%. [6]

International

In a study from Taiwan of inpatients, outpatients, and patients in the emergency department, with serum potassium levels of 6 mmol/L or greater, Kuo et al found the highest incidence to be in the emergency department (0.92%), but determined that the worst outcomes were among inpatients, with a 51% mortality rate. [7]

Sex

The male-to-female ratio is 1:1.

Mortality/Morbidity

The primary cause of morbidity and death is potassium's effect on cardiac function. [8, 9, 10] The mortality rate can be as high as 67% if severe hyperkalemia is not treated rapidly. [11]

In a study of almost 21,800 inpatients with hyperkalemia, Davis et al found that death and readmission were fairly common whether the hyperkalemia was mild, moderate, or severe. (In this report, mild, moderate, and severe were designated as >5.0-5.5 mEq/L, >5.5-6.0 mEq/L, and >6.0 mEq/L, respectively.) During their inpatient stay, normalization of potassium levels occurred in 87.7%, 86.8%, and 81.9% of the mild, moderate, and severe patients, respectively. Nonetheless, inpatient mortality rates in the mild, moderate, and severe groups were 12.3%, 15.5%, and 19.5%, respectively. Moreover, the all-cause inpatient readmission rates for the three groups at 30-90 days post discharge were 19.7-31.2%, 21.5-32.1%, and 19.6-31.4%, respectively. [12]

A study by Krogager et al indicated that in patients who need diuretic treatment following a myocardial infarction, a potassium level above or below the 3.9-4.5 mmol/L range significantly increases the mortality risk, with the highest risk (38.3% mortality rate at 90-day follow-up) found in patients with severe hyperkalemia (>5.5 mmol/L). [13]

A study by Norring-Agerskov indicated that hyperkalemia is associated with increased 30-day mortality in hip-fracture patients, with a hazard ratio of 1.93. The study included 7293 patients with hip fracture, aged 60 years or older. [14]

-

Widened QRS complexes in hyperkalemia.

-

Widened QRS complexes in a patient whose serum potassium level was 7.8 mEq/L.

-

ECG of a patient with pretreatment potassium level of 7.8 mEq/L and widened QRS complexes after receiving 1 ampule of calcium chloride. Notice narrowing of QRS complexes and reduction of T waves.